It’s a sad fact that the vast majority of silent movies in Japan have been lost thanks to human carelessness, earthquakes and the grim efficiency of the United States Air Force. The first films of hugely important figures like Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Hiroshi Shimizu have simply vanished. So we should consider ourselves fortunate that Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Kuretta Ippei — a 1926 film known in the States as A Page of Madness – has somehow managed to survive the vagaries of fate. Kinugasa sought to make a European-style experimental movie in Japan and, in the process, he made one of the great landmarks of silent cinema. You can watch it above.

Born in 1896, Kinugasa started his adult life working as an onnagata, an actor who specializes in playing female roles. In 1926, after working for a few years behind the camera under pioneering director Shozo Makino, Kinugasa bought a film camera and set up a lab in his house in order to create his own independently financed movies. He then approached members of the Shinkankaku (new impressionists) literary group to help him come up with a story. Author Yasunari Kawabata wrote a treatment that would eventually become the basis for A Page of Madness.

Though the synopsis of the plot doesn’t really do justice to the movie — a retired sailor who works at an insane asylum to care after his wife who tried to kill their child — the visual audacity of Page is still startling today. The opening sequence rhythmically cuts between shots of a torrential downpour and gushing water before dissolving into a hallucinatorily odd scene of a young woman in a rhomboid headdress dancing in front of a massive spinning ball. The woman is, of course, an inmate at the asylum dressed in rags. As her dance becomes more and more frenzied, the film cuts faster and faster, using superimpositions, spinning cameras and just about every other trick in the book.

While Kinugasa was clearly influenced by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which also visualizes the inner world of the insane, the movie is also reminiscent of the works of French avant-garde filmmakers like Abel Gance, Russian montage masters like Sergei Eisenstein and, in particular, the subjective camerawork of F. W. Murnau in Der Letzte Mann. Kinugasa incorporated all of these influences seamlessly, creating an exhilarating, disturbing and ultimately sad tour de force of filmmaking. The great Japanese film critic Akira Iwasaki called the movie “the first film-like film born in Japan.”

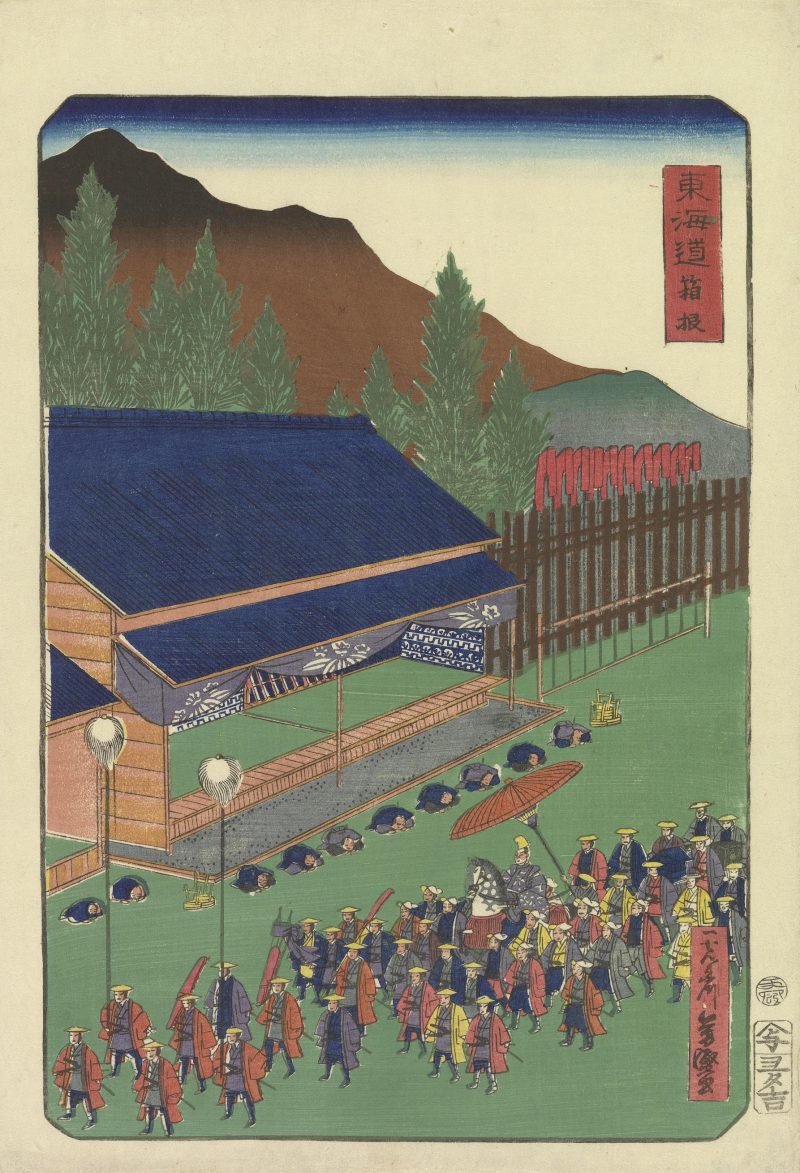

When A Page of Madness was released, it played at a theater in Tokyo that specialized in foreign movies. Page was indeed pretty foreign compared to most other Japanese films at the time. The movie was regarded, film scholar Aaron Gerow notes, as “one of the few Japanese works to be treated as the ‘equal’ of foreign motion pictures in a culture that still looked down on domestic productions.” Yet it didn’t change the course of Japanese cinema, and it was thought of as a curiosity at a time when most films in Japan were kabuki adaptations and samurai stories.

Page disappeared not long after its release and, for over 50 years, was thought lost until Kinugasa found it in his own storehouse in 1971. During that time Kinugasa received a Palme d’Or and an Oscar for his splashy samurai spectacle The Gate of Hell (1953) and Kawabata, who wrote the treatment, got a Nobel Prize in Literature for writing books like Snow Country about a lovelorn geisha.

You can find A Page of Madness on our list of Free Silent Films, which is part of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Early Japanese Animations: The Origins of Anime (1917–1931)

Akira Kurosawa & Francis Ford Coppola Star in Japanese Whisky Commercials (1980)

Wabi-Sabi: A Short Film on the Beauty of Traditional Japan

Akira Kurosawa’s 100 Favorite Movies

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.