Like gothic script in heavy metal, the fisheye album cover photo seems like a naturally occurring feature of certain psychedelic strains of music. But it has a history, as does the fisheye photograph itself. The Vox video above begins in 1906 with Johns Hopkins scientist and inventor Robert Wood, a somewhat eccentric professor of optical physics who wanted to duplicate the way fish see the world: “the circular picture,” he wrote, “would contain everything within an angle of 180 degrees in every direction, i.e. a complete hemisphere.”

Rather than putting them to underwater use, later scientists employed Wood’s ideas in astronomical observation. Their next stop was the professional photography market: the first mass-produced fisheye lens, made by Nikon, cost $27,000 in 1957. From academic journals to the pages of Life magazine: mass media brought fisheye photography into popular culture. An affordable, consumer-grade lens in 1962 brought it within the reach of the masses. For the way it compresses angles, the fisheye lens “was, and always has been, a handy tool to capture tight quarters, as well as huge spaces.”

The fisheye lens suited the Beatles phenomenon perfectly, compressing backstage hallways and stadium-sized crowds into the same hypnotically circular dimensions. “Perhaps its greatest strength was making rock stars appear larger than life.”

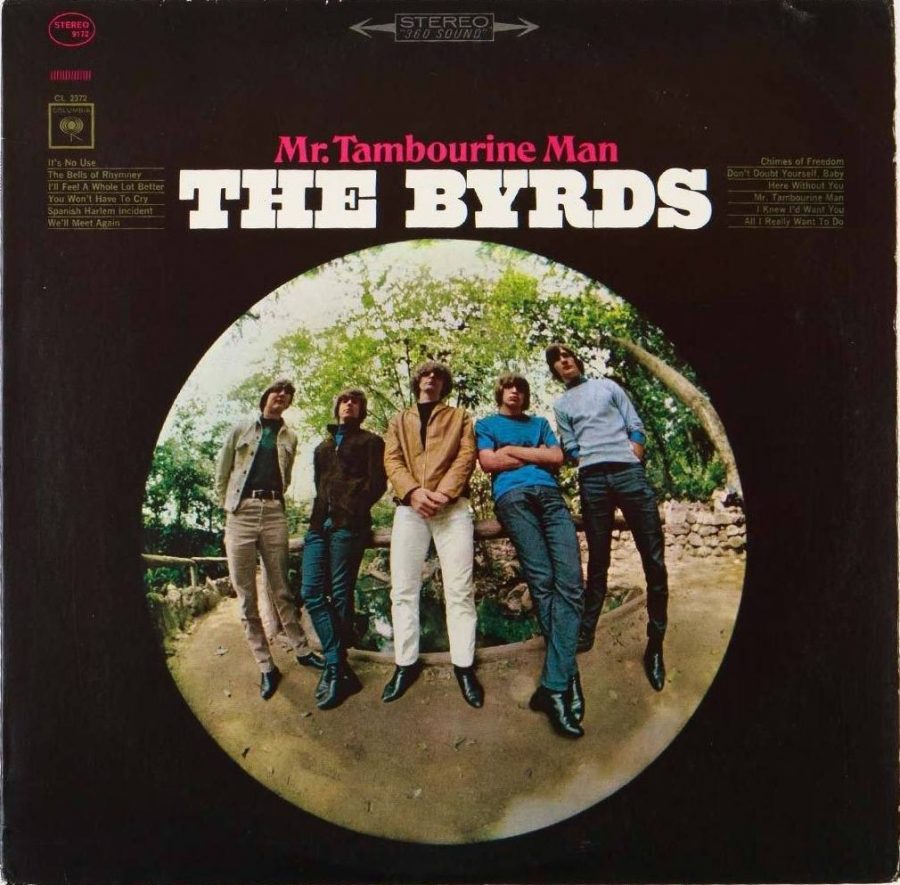

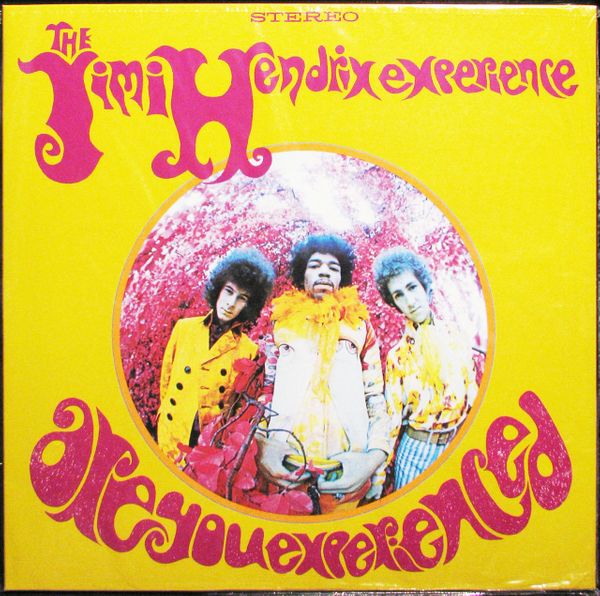

The fisheye photo “reflected the trippiness of the psychedelic era.” Although one of the earliest uses on an album cover was Sam Rivers’ Fuschia Swing Song, it soon adorned the Byrds Mr. Tambourine Man and—of course—the cover of Jimi Hendrix’s Are You Experienced. The iconic band photo of the Experience, taken by graphic designer Karl Ferris, inspired hundreds of psychedelic imitators.

Ferris thought of the fisheye photo with reference, again, not to the ocean but the stars: Hendrix’s music, he said, was “so far out that it seemed to come from outer space.” In order to introduce the band to audiences who hadn’t heard of them yet, he conceived of them as a “group traveling through space in a Biosphere on their way to bring their otherworldly space music to earth.” Inseparable from space travel after NASA’s many fisheye photos of the Apollo missions, the fisheye album cover contains entire worlds in a single droplet, and promises to transport us to the outer reaches of sound.

Related Content:

People Pose in Uncanny Alignment with Iconic Album Covers: Discover The Sleeveface Project

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness