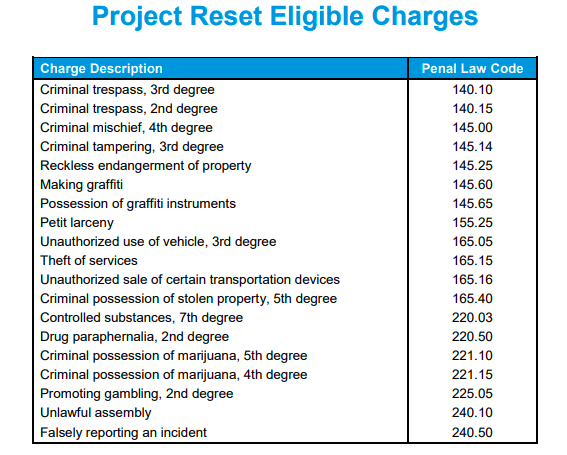

Art saves lives, and art can also save an individual from the stigma of an arrest record, provided that the arrest is for one of 15 non-violent misdemeanors.

Project Reset, a museum-based early diversion program in three of New York City’s five boroughs, aims to reframe the way youthful (and not so youthful) offenders see themselves, by considering an artwork via a collective interpretive process, before using it as the inspiration for a collage or oil pastel-based project of their own.

The stakes are higher and far more personal than they are on the average public school field trip. Upon completion of a class ranging from 2.5 to 4 hours, the participant’s record is wiped clean and their assigned court date is rendered moot.

Rather than being herded through a number of galleries, participants zero in on a single work.

At the Brooklyn Museum, participants in the under-25 age range get a crash course in Shifting the Gaze, Titus Kaphar’s intentional palimpsest, in which all the figures in a replica of Frans Hals’ Family Group in a Landscape are whited out so viewers may focus in on the only character of color, a young boy who appears to be a family servant.

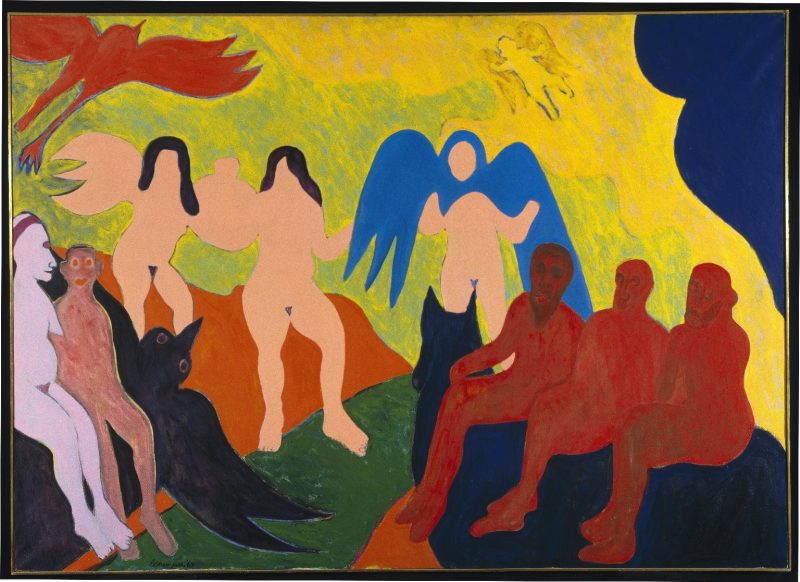

Older participants undertake a similarly deep dive on The Judgement by Bob Thompson, an African American artist who was inspired by the constant interplay between good and evil.

While this may strike some as a cushy punishment, it’s a legitimate attempt to acquaint participants with the very real impact their actions could have on future plans—including college admissions and job applications.

Manhattan District Attorney, Cyrus Vance Jr., one of Project Reset’s architects, shared a non-partisan fiscal take with City Lab’s Rebecca Bellan that may persuade naysayers who feel the program rewards budding criminals by giving them an easy out:

If you jump subway turnstiles in Manhattan, you never go to jail. You can do it 100 times and no court is ever going to send you to jail. So we spend about $2,200 to process a theft of services arrest for a $2.75 fare. Our justice system falls most heavily on communities of color, and we really need to rethink how we approach these cases, both to get better outcomes, but also to reduce the impact which is very often viewed as targeted and unfair on particular communities.

Above is a list of the non-violent misdemeanors that can channel first timers toward the aptly named Project Reset.

Related Content:

Wonderfully Offbeat Assignments That Artist John Baldessari Gave to His Art Students (1970)

The Art Institute of Chicago Puts 44,000+ Works of Art Online: View Them in High Resolution

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC for her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.