Animation fans all over the world love the films of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, but animation fans in China have never, until very recently, been able to see them on the big screen. Part of the problem has to do with the sensitivity of Chinese authorities to what sort of media enters the country — especially media from a country like Japan, with which China has not always seen eye to eye. “Miyazaki films did not open theatrically in China until a re-release of My Neighbor Totoro in December 2018,” writes Indiewire’s Zack Scharf, “one sign that the relationship between Japan and China is getting less tense.”

Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli has produced few characters as winning as Totoro — the outsized guardian of the forest who resembles a cross between a cat, an owl, and maybe a bear — and his winning over of China’s censors seemed to have opened the gates to the Middle Kingdom for the rest of Miyazaki’s beloved filmography. “The Totoro release was a huge box office success with more than $26 million,” writes Scharf, “and Spirited Away is widely expected to perform even better given its enduring popularity.” Having opened in Japan back in 2001 as 千と千尋の神隠し, or “The Spiriting-Away of Sen and Chihiro,” it stands not only as the top-grossing film of all time at the Japanese box office, but one of the several undisputed masterpieces among Miyazaki’s works.

Spirited Away tells the story of a ten-year-old girl who, lost in an abandoned amusement park, finds her way into a parallel world populated with the countless spirit creatures enumerated in the Japanese folk religion of shinto — which, as revealed in Wisecrack’s video essay “The Philosophy of Hayao Miyazaki,” figures heavily into some, and perhaps all of the master’s work. As displeasing as the presence of religion, let alone a Japanese religion, may long have been to Chinese higher-ups, the Chinese public’s enthusiasm for Miyazaki’s films can hardly be disputed.

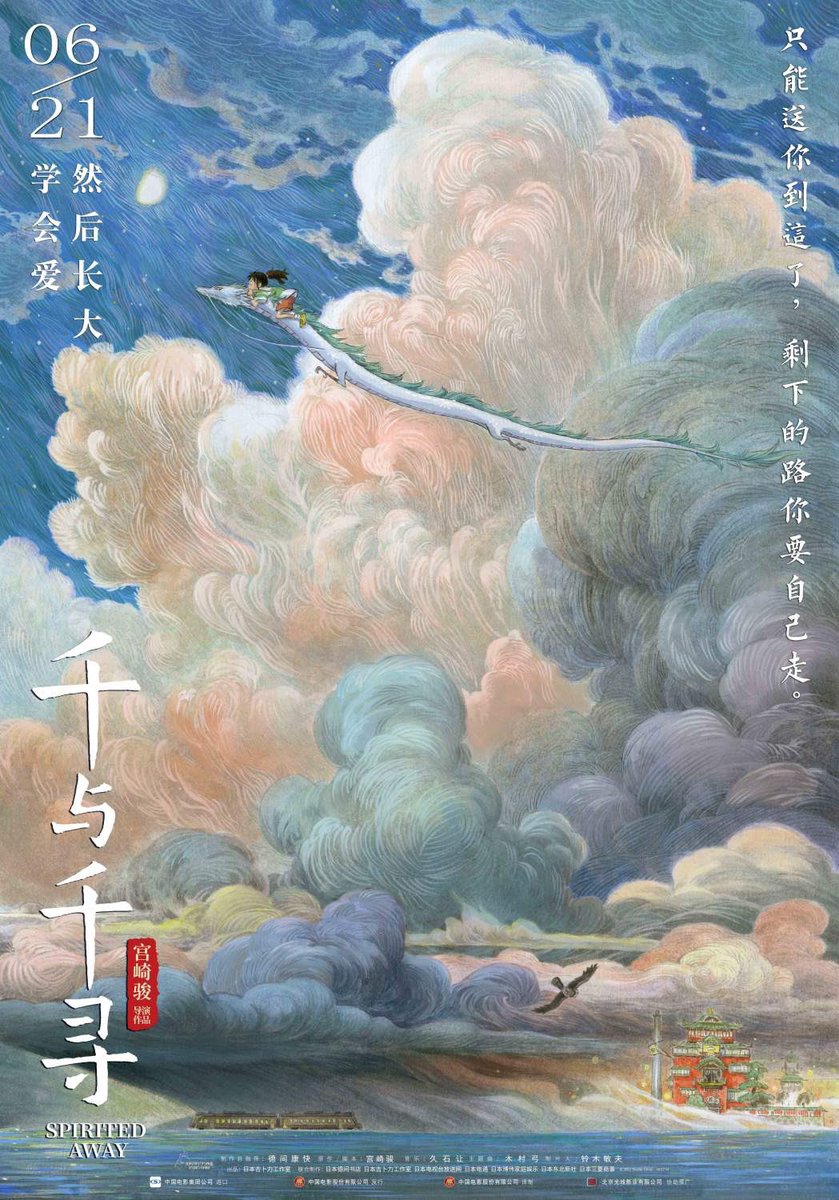

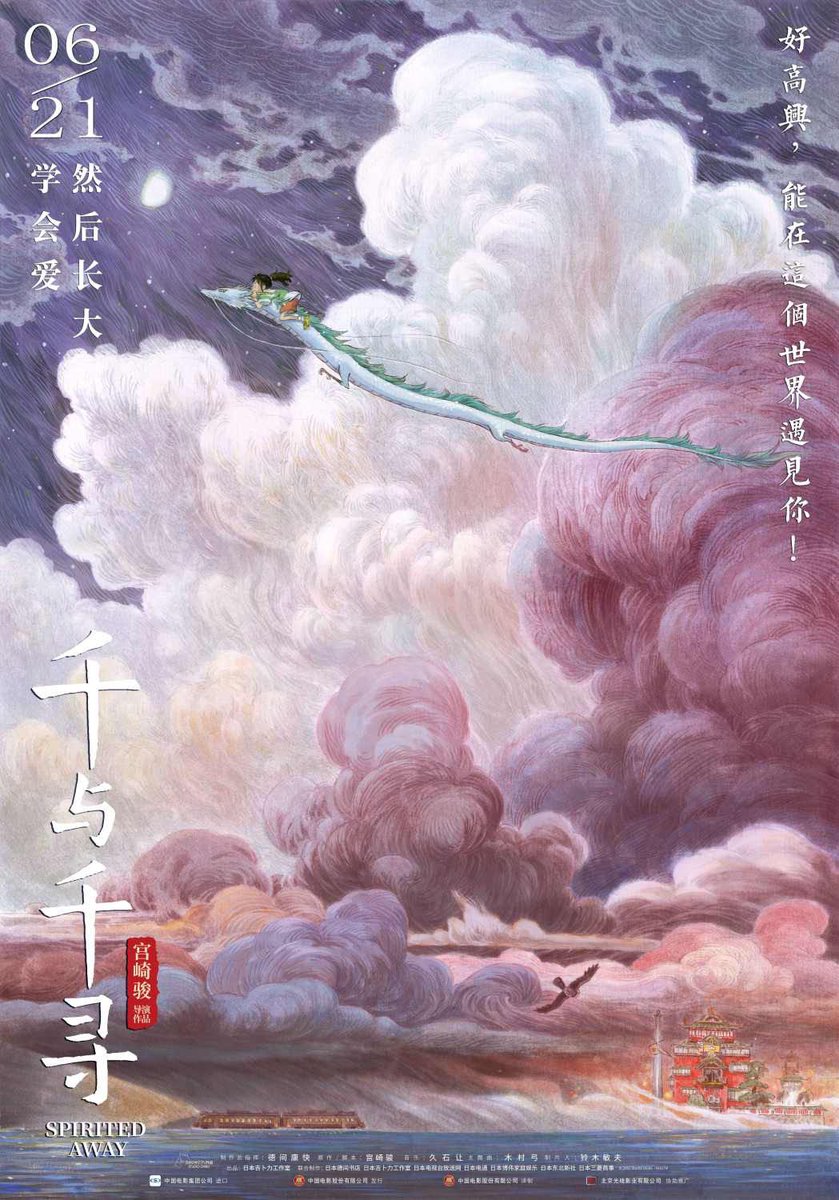

That powerful force could even return to Spirited Away the title of most successful Japanese animated film ever, which it held until Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name came along in 2017. The marketing of Spirited Away’s eighteen-year-late Chinese theatrical release, which includes this series of posters newly designed by artist Zao Dao, will certainly help give it a push. Every Ghibli enthusiast in China will certainly come out for it, and with luck, they may also be able to see the upcoming How Do You Live? — Miyazaki’s next and perhaps final film, for whose production he came out of the latest of his retirements — in theaters along with the rest of the world.

Related Content:

Watch Hayao Miyazaki’s Beloved Characters Enter the Real World

How the Films of Hayao Miyazaki Work Their Animated Magic, Explained in 4 Video Essays

Watch Hayao Miyazaki Animate the Final Shot of His Final Feature Film, The Wind Rises

Hayao Miyazaki’s Masterpieces Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke Imagined as 8‑Bit Video Games

The Simpsons Pay Wonderful Tribute to the Anime of Hayao Miyazaki

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.