What if everything you thought you knew about grunge was a lie? Maybe you’ve suspected all along! But even if you were there, or somewhere, in that time of abysmally low internet literacy and connectivity, when every traditional media outlet was flannel, floppy hair, mopey half-protests, festivals, Seattle.… When you could save $6-$13 on “women’s grunge” and “$5 on kids’ grunge too!” at major department store chains…

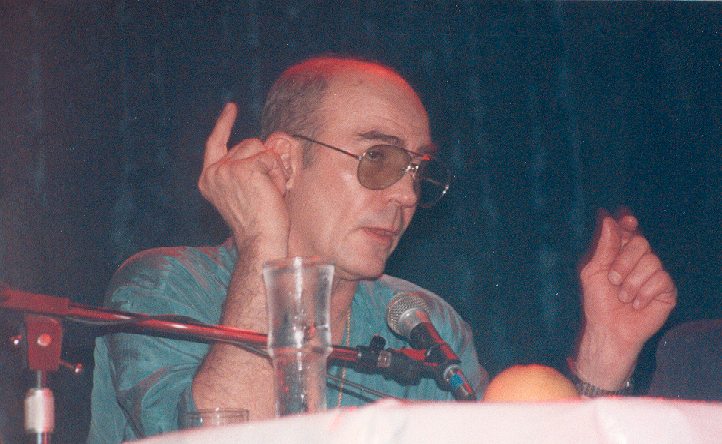

But we may still remember grunge as a movement—with charismatic leaders and tragic heroes. A movement to reclaim serious, heavy, emotional hair rock from the profoundly unserious hair bands of the 80s. The first wave of Pacific Northwest bands to emerge with Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam were earnest and well-meaning and “primal,” says Bruce Pavitt, co-founder of the legendary Seattle record label Sub Pop.

Sub Pop midwifed the scene by signing so many of the bands that made it big, cultivating the sound and look of dirty, angry backwoodsmen with guitars. “Grunge Made Blue-Collar Culture Cool,” wrote Steven Kurutz in The New York Times Style Section just a few days ago, an implicit acknowledgment that the mostly-white and largely male scene sold a particular image of blue-collar that resonated, says Pavitt, because it represented an “ ‘American archetype.”

Pavitt and co-founder Jonathan Poneman were diehard fans of the music but they were no starry-eyed idealists—they understood exactly how to sell the region’s quirks to a national and international media. “It could have happened anywhere,” Poneman has said, “but there was a lucky set of coincidences. [Photographer] Charles Peterson was here to document the scene, [producer] Jack Endino was here to record the scene. Bruce and I were here to exploit the scene.”

![]()

But what was the scene? Was it “Grunge”? What is “Grunge”? How do you pronounce “Grunge”? What do “Grunge” people eat? After being peppered with one too many questions when the shockwave of Nirvana’s major label debut Nevermind hit in 1992, Poneman referred a reporter to a former Sub Pop employee, Megan Jasper, then working as a sales rep for Caroline records. The reporter, Rick Marin, was calling from The New York Times’ Style Section, asking for help compiling a grunge lexicon. What kinds of things do “Grunge” people say?

“By then,” writes Alan Siegel at The Ringer, “only outsiders earnestly used the term ‘grunge’ as a noun.” It was, says Charles Cross, former editor of alternative paper The Rocket, “an overhyped, inflated word that doesn’t have actual meaning in Seattle.” As for grunge slang, such a thing “didn’t exist.” The only thing to do, Jasper decided, was “react by trying to make fun of it,” she says. She had done the very same thing months earlier, when British magazine Sky made the same request. “I gave them a bunch of fake shit.”

As she says in the interview clip at the top, she asked Marin to toss out normal words and she would give him “grunge” equivalents. “I kept escalating the craziness of the translations because anyone in their right mind would go, ‘Oh, come on, this is bullshit.’… but it never happened because he was concentrating so hard on getting the information right.” Thus, the grunge lexicon below, published in The New York Times in 1992. (“All subcultures speak in code,” goes the caption. This one would be appearing in malls nationwide.)

- bloated, big bag of bloatation – drunk

- bound-and-hagged – staying home on Friday or Saturday night

- cob nobbler – loser

- dish – desirable guy

- fuzz – heavy wool sweaters

- harsh realm – bummer

- kickers – heavy boots

- lamestain – uncool person

- plats – platform shoes

- rock on – a happy goodbye

- score – great

- swingin’ on the flippity-flop – hanging out

- tom-tom club – uncool outsiders

- wack slacks – old ripped jeans

It’s unlikely Marin ever traveled to Seattle and tried to bond with fellow kids, or he would not have published Jasper’s hoax glossary in an article otherwise critical of the mainstreaming of grunge. Marin compared the phenomenon to “the mass-marketing of disco, punk and hip-hop. Now with the grunging of America, it’s happening again. Pop will eat itself, the axiom goes.” It’s a thorough, well-sourced piece that quotes many of the scene’s founders, including Poneman, never suspecting they might be having a laugh.

The fake news grunge lexicon was a huge hit in Seattle, where Jasper was celebrated by her friends and family. “I got a very nice pat on the back,” she says. People clipped the lexicon to their shirts at shows. Indie label C/Z records then printed t‑shirts. “Lamestain” appeared on one. “Harsh Realm” on another. Mudhoney spread around Jasper’s slang in a Melody Maker interview with straight faces. It should have been debunked immediately “but this was 1992,” writes Siegel, “Snopes wasn’t around yet. Hell, The New York Times was still four years away from launching a website.”

Then, writer and reporter Thomas Frank called Jasper and asked, “there’s no way this is real, right?” Immediately, she responded, “Of course it’s not real.” Frank published the scoop in 1993; the Times smeared him as a hoaxer to discredit the revelation. The Baffler faxed the Times this note: “When The Newspaper of Record goes searching for the Next Big Thing and the Next Big Thing piddles on its leg, we think that’s funny.” These days, we might expect a Twitter war.

No one Siegel interviews seems to have been particularly upset about the whole thing. Marin’s “eyebrow is totally raised” throughout his piece, says his former editor Penelope Green. (Marin himself declined to be interviewed.) But the story has far less to do with one credulous reporter working a deadline and more to do with his argument—grunge had been rapidly packaged and sold, and by The Times, no less! But maybe its image was sort of a joke to begin with, one that now gets such straight-faced, reverent, sealed-behind-glass-cases treatment that you have to laugh.

Related Content:

The Power of Eddie Vedder’s Voice: Hear Isolated Vocal Tracks from Three Classic Pearl Jam Songs

A Massive 800-Track Playlist of 90s Indie & Alternative Music, in Chronological Order

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness