Elizabeth Cotten Wrote “Freight Train” at 11, Won a Grammy at 90, and Changed American Music In-Between

When I first moved to North Carolina, one of the first visits I made was to the little town of Carrboro. There sits a plaque on East Main commemorating Elizabeth “Libba” Cotton: “Key Figure. 1960s folk revival. Born and raised on Lloyd Street,” just west of Chapel Hill, in 1893. It’s an accurate-enough description of Cotten’s importance to 60s-era folk, but the limited space on the sign elides a much richer story, with a typical musical theft and unusual late-life triumph.

The sign sits next to a retired train depot converted into a restaurant called The Station, which advertises two claims to fame—R.E.M. played their first show outside of Georgia there in 1980, and Elizabeth Cotten “was inspired to write her famous folk song, ‘Freight Train,’ in the early 1900s as a tribute to the trains that stopped in Carrboro, which she could hear at night from the bedroom of her childhood home.” The song became a standard in American folk and British skiffle.

“Freight Train” was credited for years to two British songwriters, who claimed it as their own in the mid-fifties. However, not only did Cotten write the song, but she did so decades earlier when she was only 11 or 12 years old. It first made its way to England by way of Peggy Seeger, who had heard it from her onetime nanny, Libba, when she was young. “Freight Train” was then picked up by several singers and groups, including The Quarrymen, the skiffle band that would become The Beatles.

Cotten “built her musical legacy,” writes Smithsonian’s Folkways, “on a firm foundation of late 19th- and early 20th-century African-American instrumental traditions.” She had a keen grasp of her musical roots, with her own innovations. A self-taught guitar and banjo player, she flipped the instruments over to play them left-handed. She did not restring them, however, but played them upside-down, developing a captivating fingerstyle technique “that later became widely known as ‘Cotten style.’”

Persuaded by her church to stop playing “worldly music,” Cotten all but gave it up and moved to Washington, DC. There, she might have faded into obscurity, the story of “Freight Train” highlighting just one more injustice in a long history of misappropriated black American music. But the folk-singing Seeger family worked to secure her recognition and relaunch her career.

Cotten first “landed entirely by accident” with the Seegers after returning a young, lost Peggy to her mother Ruth at a Washington D.C. department store where Cotten had been working. The family hired her on as help, and did not learn of her talent until later. After her song became famous, Mike Seeger recorded Cotten singing “Freight Train” and a number of other tunes from “the wealth of her repertoire” in 1957. He was eventually able to secure her the credit for the song.

Thanks to these recordings, Cotten “found herself giving small concerts in the homes of congressmen and senators, including that of John F. Kennedy.” In 1958, Seeger recorded her first album, made when she was sixty-two, Elizabeth Cotten: Negro Folk Songs and Tunes. “This was one of the few authentic folk-music albums available by the early 1960s,” notes Smithsonian, “and certainly one of the most influential.”

Cotten’s story (and her guitar playing) is reminiscent of that of Mississippi John Hurt, who left music for farming in the late 20s, only to be rediscovered in the early sixties and go on to inspire the likes of fingerstyle legends John Fahey and Leo Kottke. But Cotten doesn’t get enough credit in popular music for her influence, despite writing songs like “Freight Train,” “Oh, Babe, It Ain’t No Lie,” and “Shake Sugaree,” covered by The Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, and a host of traditional folk artists.

Fans of folk and acoustic blues, however, will likely know her name. She toured and performed to the end of her life, giving her last concert in New York in 1987, just before her death at age 94. The recording industry gave Cotten her due as well. In 1984, when she was 90, she won a Grammy in the category of “Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording.” Two years later, she was nominated again, but did not win.

The recognition was a long time coming. In 1963, when Peter, Paul & Mary had a hit with their version of “Freight Train,” few people outside of a small circle knew anything about Elizabeth Cotten. In 1965, The New York Times published an article about her headlined “Domestic, 71, Sings Songs of Own Composition in ‘Village,’” as Nina Renata Aron points out in a profile at Timeline.

But thanks to her own quiet persistence and some famous benefactors, Elizabeth Cotten is remembered not as a housekeeper and nanny who happened to write some songs, but as a Grammy-winning folk legend and “key figure” in both American and British musical history. In addition to her Grammy and other awards, she received the Burl Ives Award in 1972 and was included in the company of Rosa Parks and Marian Anderson in Brian Lanker’s book of portraits I Dream a World: Black Women Who Changed America.

In 1983, Syracuse, New York, where she spent her last years and now rests, named a park after her. And it may have taken them entirely too long to catch up to her legacy, but in 2013, the state of North Carolina recognized one of its most influential daughters, putting up the Historical Marker sign in her honor.

In the videos here, see Cotten, in her spry, prolific old age, play “Freight Train,” at the top, “Spanish Flang Dang” and “A Jig,” further up, in 1969, and “Washington Blues” and “I’m Going Away,” above in 1965.

Related Content:

Watch Rock Pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe Wow Audiences With Her Gospel Guitar

Pete Seeger Teaches You How to Play Guitar for Free in The Folksinger’s Guitar Guide (1955)

Download Images From Rad American Women A‑Z: A New Picture Book on the History of Feminism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Classic Children’s Books Now Digitized and Put Online: Revisit Vintage Works from the 19th & 20th Centuries

Children’s books are big business. And the market has never been more competitive. Bestselling, character-driven series spawn their own TV shows. Candy-colored readers feature kids’ favorite comic and cartoon characters. But kids’ books can also be fine art—a venue for well-written, finely-illustrated literature. And they are a serious subject of scholarship, offering insights into the histories of book publishing, education, and the social roles children were taught to play throughout modern history.

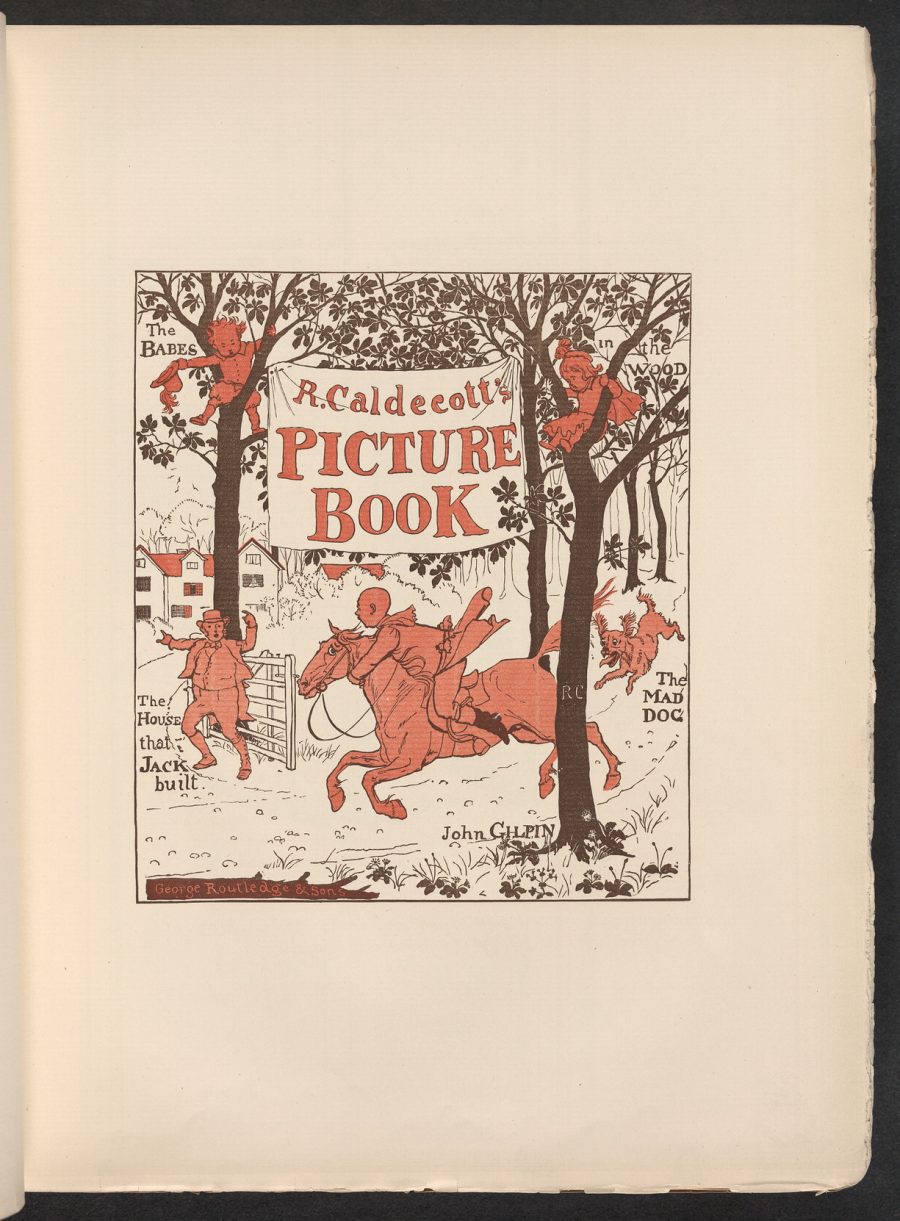

Digital archives of children’s books now make these histories widely accessible and preserve some of the finest examples of illustrated children’s literature. The Library of Congress’ new digital collection, for example, includes the 1887 Complete Collection of Pictures & Songs, illustrated by English artist Randolph Caldecott, who would lend his name fifty years later to the medal distinguishing the highest quality American picture books.

The LoC’s collection of 67 digitized kids’ books from the 19th and 20th centuries includes biographies, nonfiction, quaint nursery rhymes, the Gustave Doré-illustrated edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, and a number of other titles sure to charm grown-ups, if not, perhaps, many of today’s young readers.

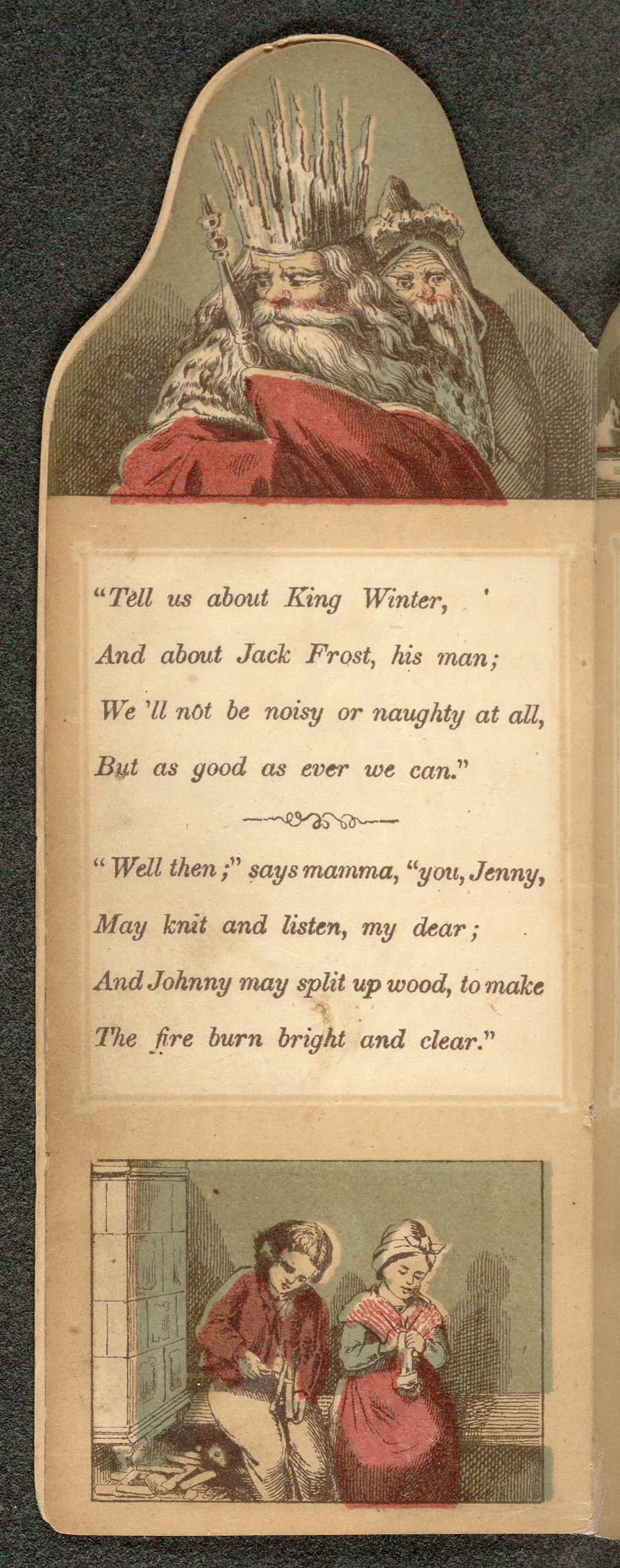

But who knows, King Winter—an 1859 tale in verse of a proto-Santa Claus figure, in a book partially shaped like the outline of the title character’s head—might still captivate. As might many other titles of note.

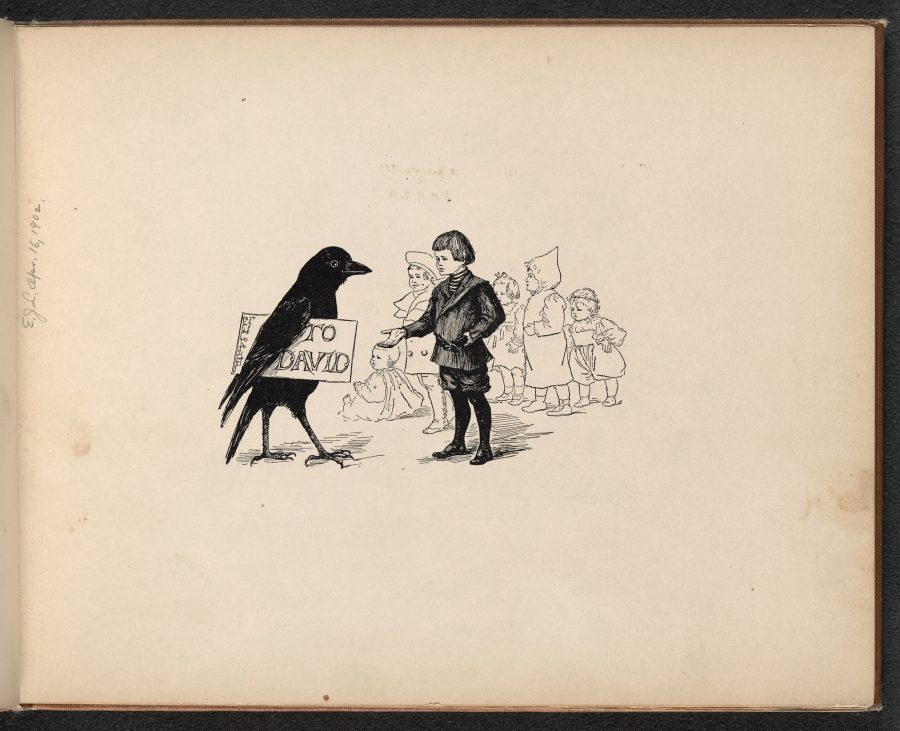

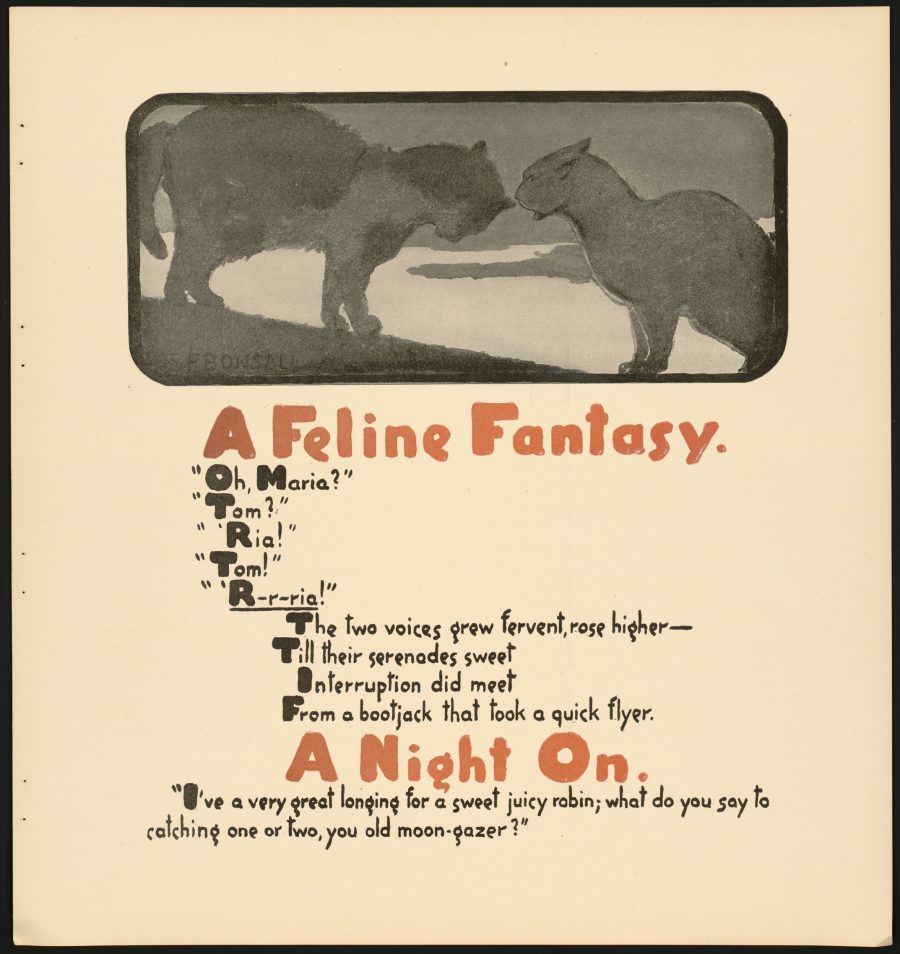

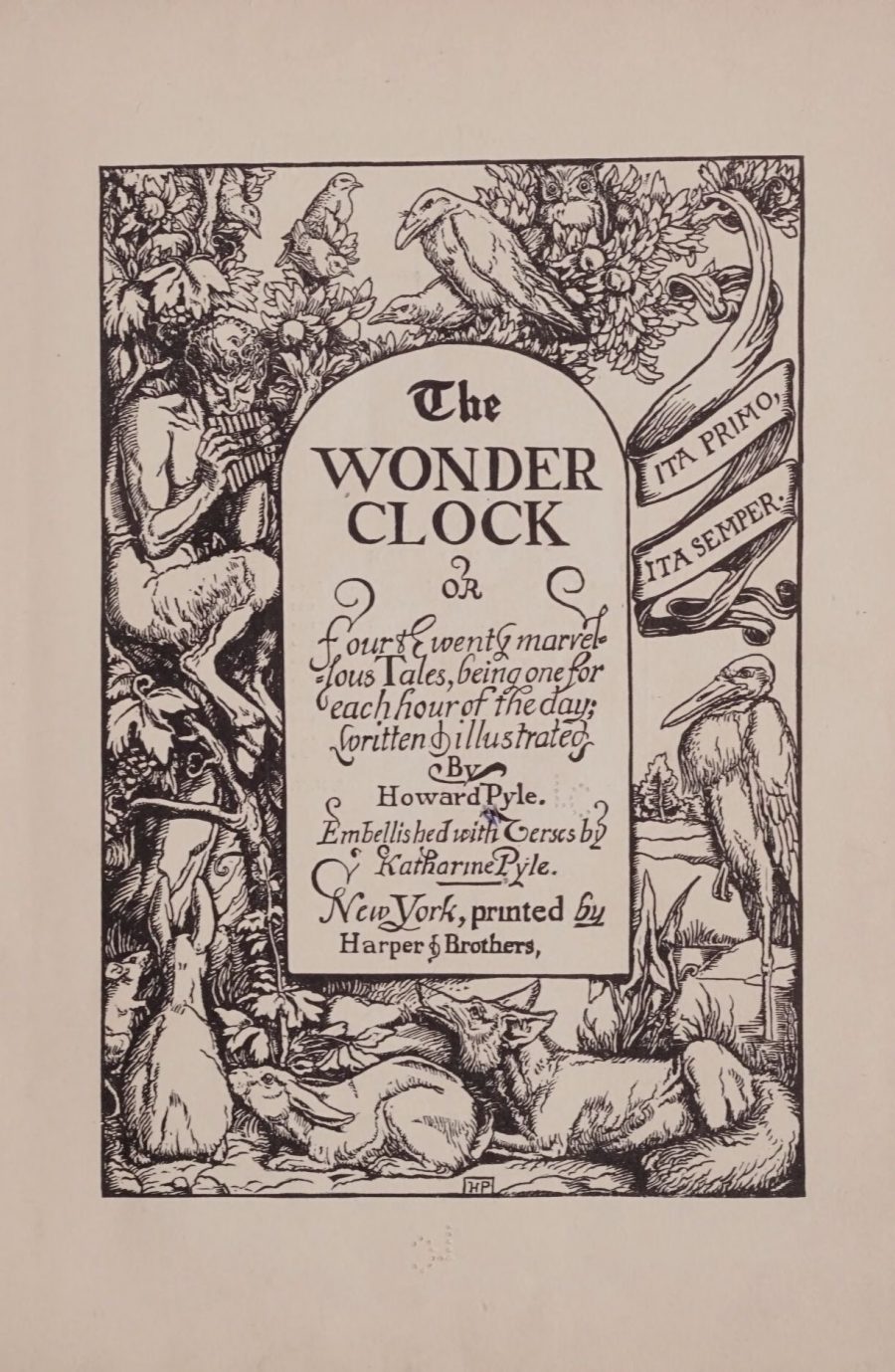

A sly collection of stories from 1903 called The Book of the Cat, with “facsimiles of drawings in colour by Elisabeth F. Bonsall”; a book of “Four & twenty marvellous tales” called The Wonder Clock, written and illustrated by Howard Pyle in 1888; and Edith Francis Foster’s 1902 Jimmy Crow about a boy named Jack and his boy-sized crow Jimmy (who could deliver messages to other young fancy lads).

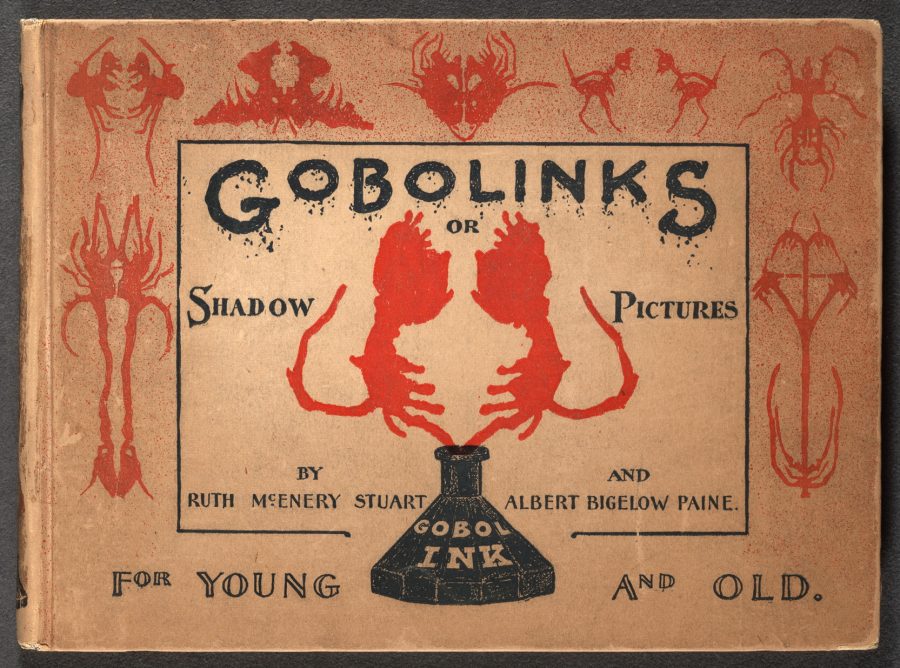

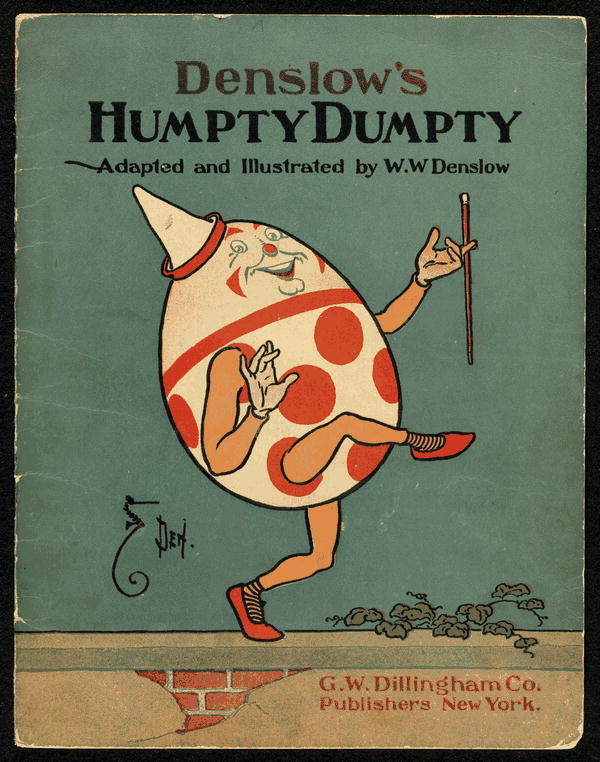

An 1896 book called Gobolinks introduces a popular inkblot game of the same name that predates Hermann Rorschach’s tests by a couple decades. Other highlights include “examples of the work of American illustrators such as W.W. Denslow, Peter Newell… Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway,” writes the Library on its blog. The digitized collection debuted to mark the 100th anniversary of Children’s Book Week, celebrated during the last week of April in all 50 states in the U.S.

“It is remarkable,” says Lee Ann Potter, director of the LoC’s Learning and Innovation Office, “that when the first Children’s Book Week was celebrated, all of the books in the online collection… already existed.” Now they exist online, not only because of the technology to scan, upload, and share them, but “because careful stewards insured that these books have survived.”

Digital versions of today’s kids books could mean that there is no need to carefully preserve paper copies for posterity. But we can be grateful that archivists and librarians of the past saw fit to do so for this fascinating collection of children’s literature. The theme of this year’s Children’s Book Week—Read Now, Read Forever—“looks to the past, present, and most important, the future of children’s books.” Enter the Library of Congress digital collection of children’s books from over a century ago (and see the other sizable online archives at the links below) to visit their past, and imagine how vastly different their future might be.

Related Content:

A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA

Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Watch Six New Short Alien Films: Created to Celebrate the 40th Anniversary of Ridley Scott’s Film

Alien came out 40 years ago this month, not that its age shows in the least. The terror of the ever-diminishing crew of the Nostromo trapped on their ship with the merciless extraterrestrial monster of the title remains as visceral as it was in 1979, and the dank, pre-digital confines of its setting have taken on a retro patina that successive generations of filmmakers struggle to recreate for themselves.

Now, in a series of brand new short films set in the Alien universe, you can see how six young filmmakers pay tribute to Ridley Scott’s original film and its cinematic legacy, each in their own way. These shorts come as the fruits of an initiative launched by 20th Century Fox to mark 40 years of Alien.

“Developed by emerging filmmakers selected from 550 submissions on the Tongal platform,” writes Collider’s Dave Trumbore, “the anniversary initiative focused on finding the biggest fans of the Alien franchise to create new, thrilling stories for the Alien fandom.”

These stories include many of the elements that fandom has come to expect — isolated and endangered spacefarers, bleak colonies on distant planets, tough women, fearsome creatures lurking in the darkness, escape pods, chest-bursting — as well a few it hasn’t. Indiewire’s Michael Nordine highlights Noah Miller’s Alone, “which follows a woman named Hope who’s hurtling through space on her lonesome. She eventually gains access to a restricted part of her ship after a system malfunction, and you can probably guess what’s on the other side of that sealed-off door.” But you certainly won’t be able to guess what happens next.

Nordine also has praise for the protagonist of the Spears Sisters’ Ore: “A miner about to welcome her latest grandchild, she puts herself in harm’s way rather than risk letting the latest alien specimen make it out of the mine and threaten the colony (and, more to the point, her family) above. That’s a simple, familiar tack, but it’s well told — something true of most Alien stories.” Collectively, he writes, these shorts “emphasize what makes Alien such an enduring franchise: its industrial, working-class environs full of clunky green-screen computers and disgruntled laborers; its bleak view of the corporate bureaucrats who enable the xenomorphs’ carnage by trying to control them and writing off their underlings as collateral damage; and, of course, its heroines.”

Taking pitches from fans through a crowdsourcing platform and distributing the resulting films on Youtube may seem like an almost parodically 21st-century way of extending a franchise that began in the 1970s, but testing out different filmmakers’ visions has long been a part of the greater Alien project: the sequels directed in the 1980s and 90s by James Cameron, David Fincher, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet hinted at the great variety of possibilities laid down by Scott’s original, the cinematic standard-bearer for the contest of wills between man and alien — or rather, woman and alien.

Related Content:

High School Kids Stage Alien: The Play and You Can Now Watch It Online

Sigourney Weaver Stars in a New Experimental Sci-Fi Film: Watch “Rakka” Free Online

Three Blade Runner Prequels: Watch Them Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.