The word Machiavellian has come to invariably refer to an “unscrupulous schemer for whom the ends justify the means,” notes the animated TED-Ed video above, a description of characters “we love to hate” in fiction past and present. The adjective has even become enshrined in psychological literature as one third of the “dark triad” that also features narcissism and psychopathy, personalities often mistaken for the Machiavellian type.

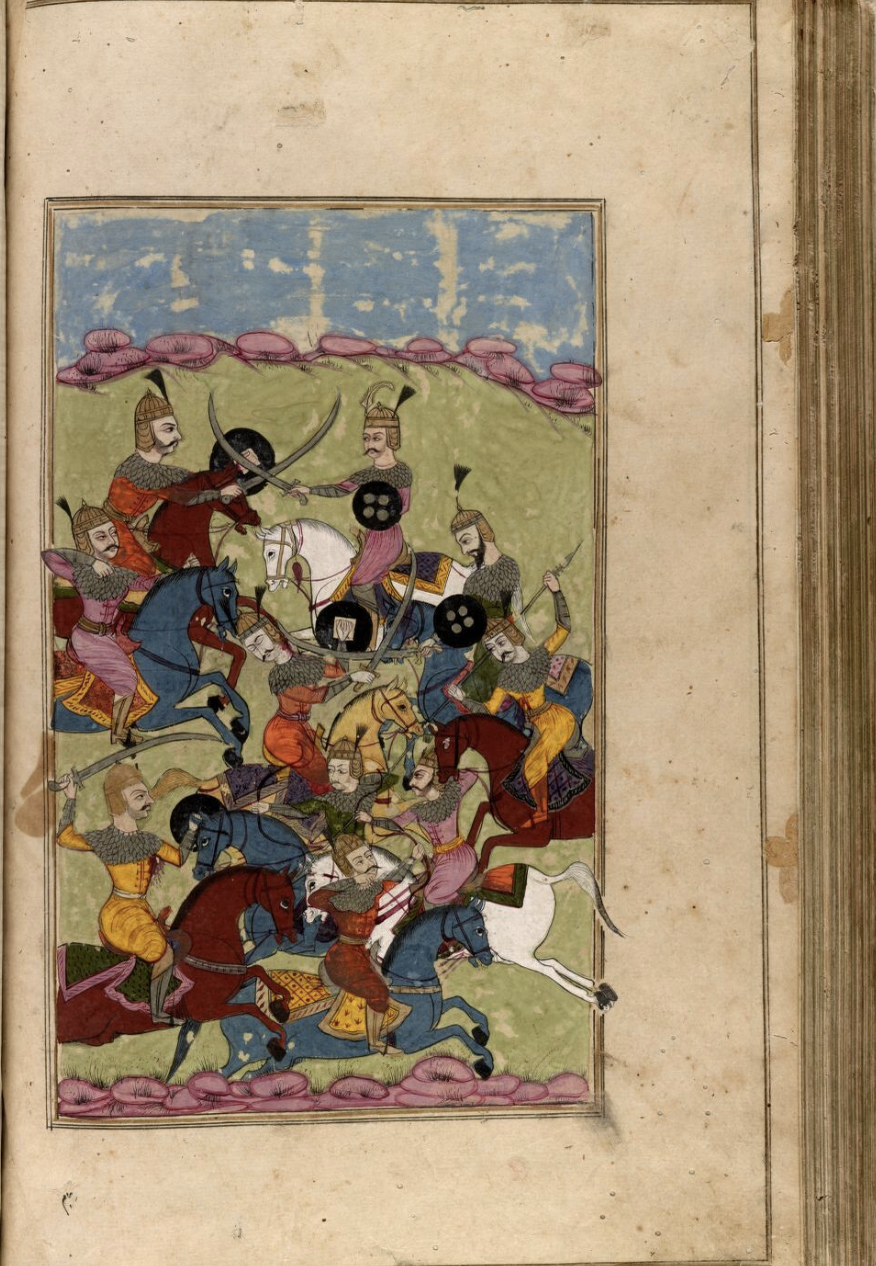

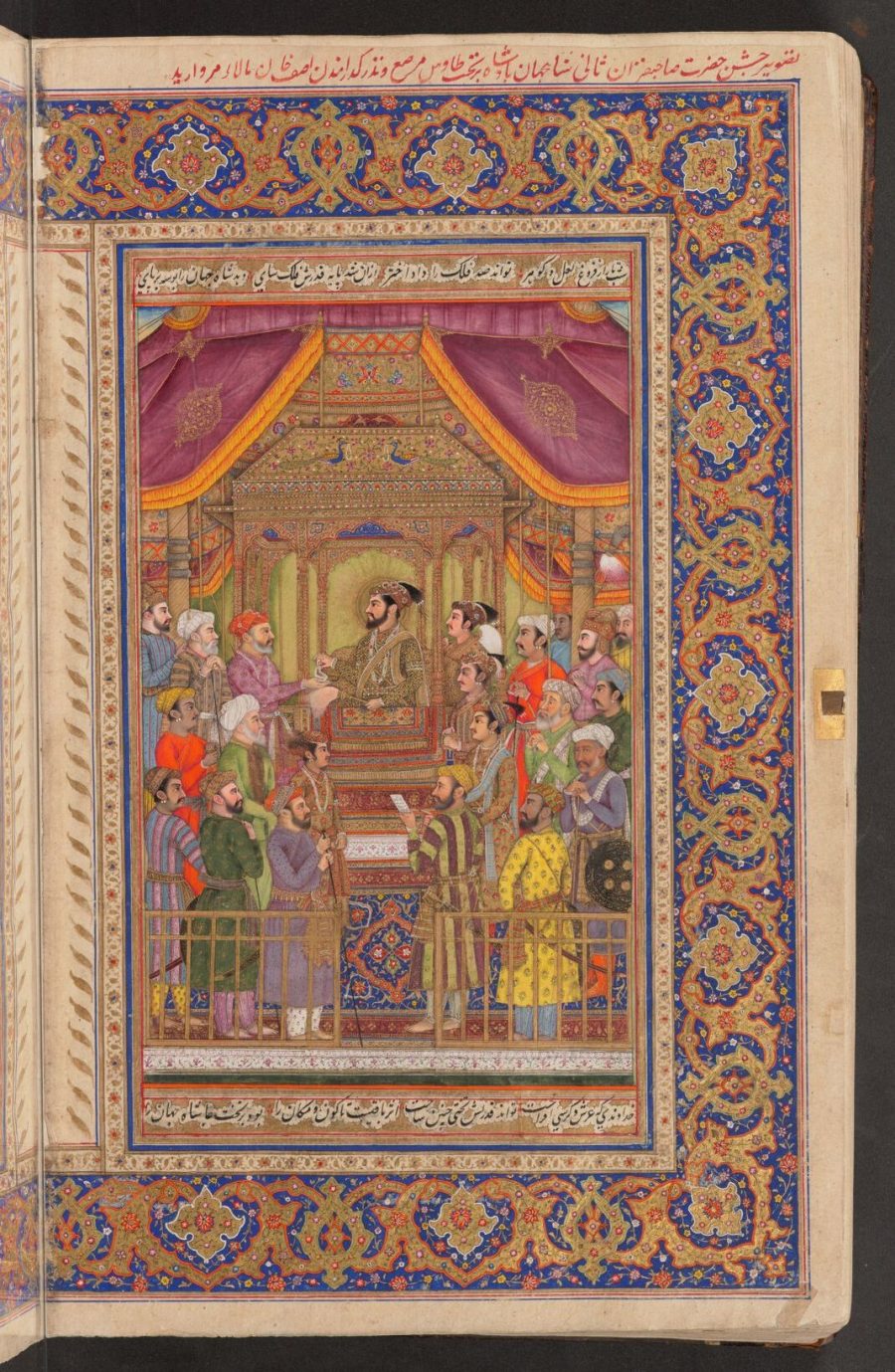

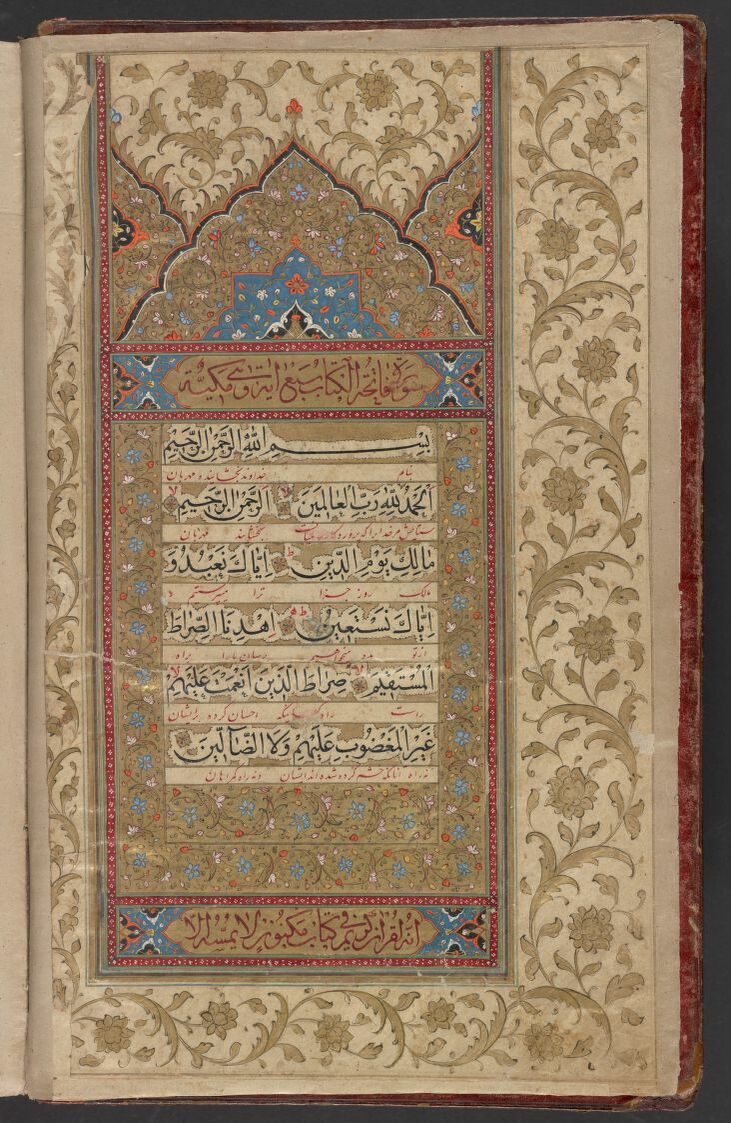

The term’s “lasting notoriety comes from a brief political essay known as The Prince,” written by Renaissance Italian writer and diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli and “framed as advice to current and future monarchs.” The Prince and its author have acquired such a fearsome reputation that they seem to stand alone, like the work of the Marquis de Sade and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, who likewise lent their names to the psychology of power. But Machiavelli’s book is part of “an entire tradition of works known as ‘mirrors for princes’ going back to antiquity.”

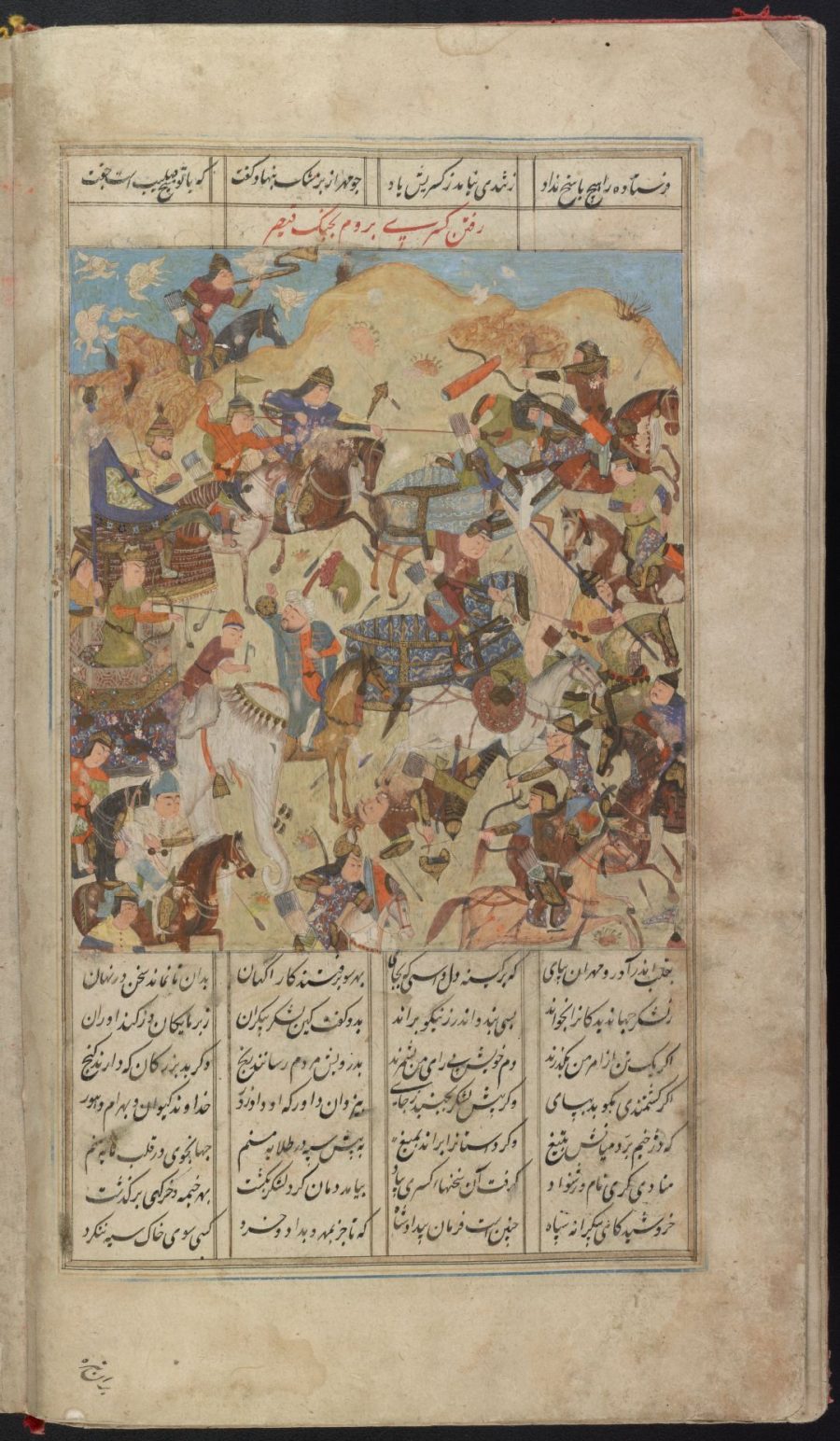

Machiavelli innovated on the tradition by casting fuzzy abstractions like justice and virtuousness aside to focus solely on virtù, the classical Italian word derived from the Latin virtus (manhood), which had little to do with ethics and everything to do with strength, bravery, and other warlike traits. Though thinkers in the tradition of Aristotle argued for centuries that civic and moral virtue may be synonymous, for Machiavelli they most certainly were not, it seems. “Throughout [The Prince] Machiavelli appears entirely unconcerned with morality except insofar as it’s helpful or harmful to maintaining power.”

The work became infamous after its author’s death. Catholics and Protestants both blamed Machiavelli for the others’ excesses during the bloody European religious wars. Shakespeare coined Machiavel “to denote an amoral opportunist.” The line to contemporary usage is more or less direct. But is The Prince really “a manual for tyranny”? The book, after all, recommends committing atrocities of all kinds, oppressing minorities, and generally terrifying the populace as a means of quelling dissent. Keeping up the appearance of benevolence might smooth things over, Machiavelli advises, unless it doesn’t. Then the ruler must do whatever it takes. The guiding principle here is that “it is much safer to be feared than loved.”

Was Machiavelli an “unsentimental realist”? A Renaissance Kissinger, so to speak, who saw the greater good in political hegemony no matter what the cost? Or was he a neo-classical philosopher hearkening back to antiquity? He “never seems to have considered himself a philosopher,” writes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy—“indeed, he often overtly rejected philosophical inquiry as beside the point.” Or at least he seemed to have rejected the Christian-influenced humanism of his day. Nonetheless, “Machiavelli deserves a place at the table in any comprehensive survey of philosophy,” not least because “philosophers of the first rank did (and do) feel compelled to engage with his ideas.”

Of the many who engaged with Machiavelli, Isaiah Berlin saw him as reclaiming ancient Greek values of the state over the individual. But there’s more to the story, and it includes Machiavelli’s political biography as a defender of republican government and a political prisoner of those who overthrew it. On one reading, The Prince becomes a “scathing description” of how power actually operates behind its various masks; a guide not for princes but for ordinary citizens to grasp the ruler’s actions for what they are truly designed to do: maintain power, purely for its own sake, by any means necessary.

Related Content:

Salman Rushdie: Machiavelli’s Bad Rap

What “Orwellian” Really Means: An Animated Lesson About the Use & Abuse of the Term

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness