The 16th century was a thrilling time for books, at least for those who could afford them: building a respectable personal library (even if it didn’t include novelties like the books that open six different ways and the wheels that made it possible to rotate through many open books at once) took serious resources. Hernando Colón, the illegitimate son of Christopher Columbus, seems to have commanded such resources: as The Guardian’s Alison Flood writes, he “made it his life’s work to create the biggest library the world had ever known in the early part of the 16th century. Running to around 15,000 volumes, the library was put together during Colón’s extensive travels” and ultimately contained everything from the works of Plato to posters pulled from tavern walls.

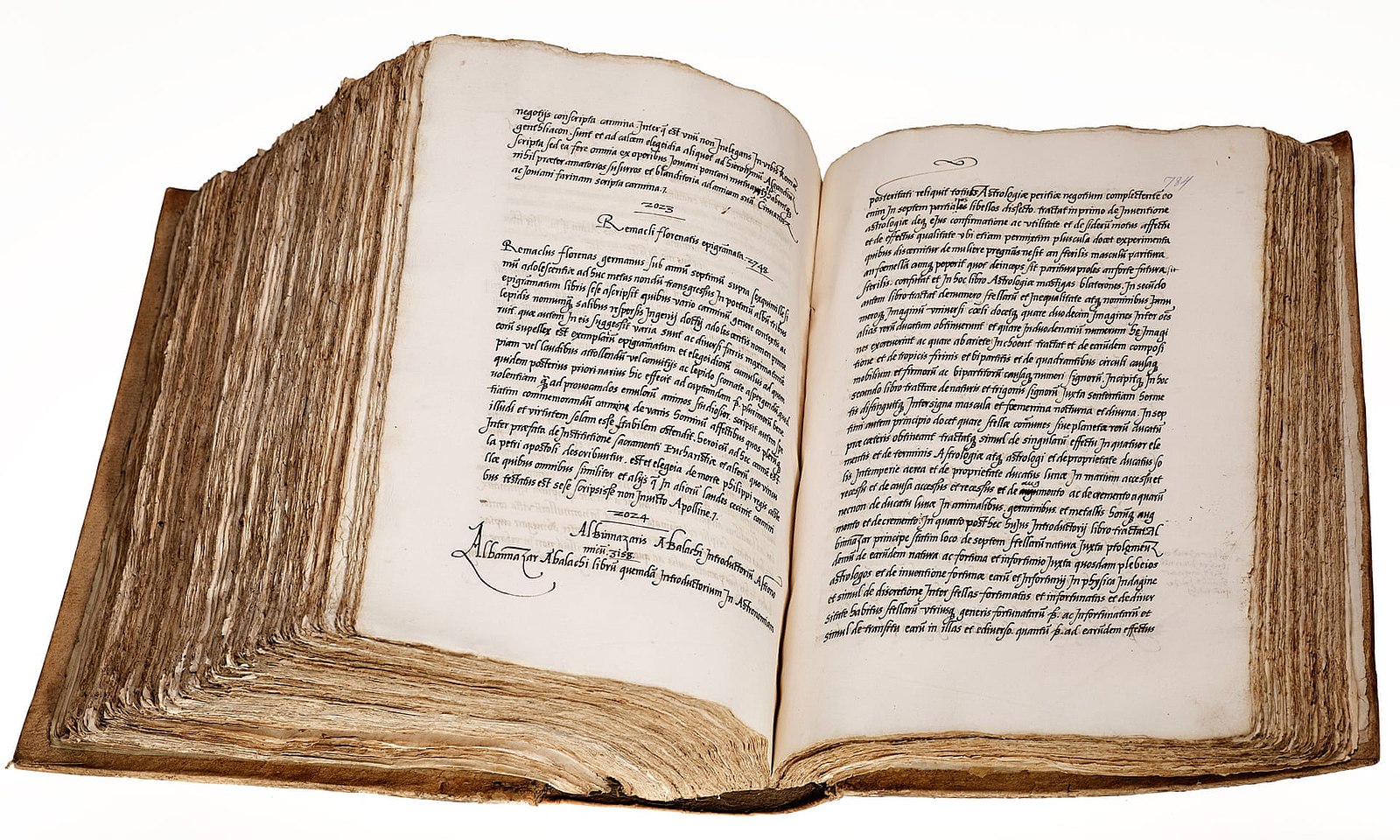

Alas, this ambitious library, meant to encompass all languages, cultures, and forms of writing, is now mostly lost. “After Colón’s death in 1539, his massive collection ultimately ended up in the Seville Cathedral, where neglect, sticky-fingered bibliophiles, and the occasional flood reduced the library to just 4,000 volumes over the centuries,” writes Smithsonian.com’s Jason Daley. But we now know what it contained, thanks to the discovery just this year of the Libro de los Epítomes, or “Book of Epitomes,” the library’s foot-thick catalog that not only lists the volumes it contained but describes them as well. “Colón employed a team of writers to read every book in the library and distill each into a little summary in Libro de los Epítomes,” Flood writes, “ranging from a couple of lines long for very short texts to about 30 pages for the complete works of Plato.”

The Libro de los Epítomes turned up earlier this year in another collection, that of an Icelandic scholar by the name of Árni Magnússon who left his books to the University of Copenhagen when he died in 1730. Fewer than 30 of the 3,000 texts in Magnússon’s mostly Icelandic and other Scandinavian-language collection (detailed images of which you can see at Typeroom) are written in Spanish, which perhaps explains why the Libro de los Epítomes went overlooked for more than 350 years. Rediscovered, it now offers a wealth of information on thousands and thousands of books from five-centuries ago, many of which have long since passed out of existence.

Colón’s uniquely exhaustive library catalog opens a window onto not just what 16th-century Europeans were reading, but how they were reading — and how the very nature of reading was evolving. “This was someone who was, in a way, changing the model of what knowledge is,” Daley quotes Colón’s biographer Edward Wilson-Lee as observing. “Instead of saying ‘knowledge is august, authoritative things by some venerable old Roman and Greek people,’ he’s doing it inductively: taking everything that everyone knows and distilling it upwards from there.” The comparisons to “big data and Wikipedia and crowdsourced information” almost make themselves, as do the references to a certain 20th-century Spanish-language writer with an interest in history, language, and knowledge as represented in books extant and otherwise. If the Libro de los Epítomes didn’t exist, Jorge Luis Borges would have had to invent it.

via the Guardian

Related Content:

The Rise and Fall of the Great Library of Alexandria: An Animated Introduction

A Medieval Book That Opens Six Different Ways, Revealing Six Different Books in One

Watch Umberto Eco Walk Through His Immense Private Library: It Goes On, and On, and On!

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.