The usual irregularities and shenanigans notwithstanding, the voting patterns of the U.S. electorate may undergo a sea change in the coming decades as the numbers of people who identify as non-religious continue to rise. One of the biggest demographic stories of the last few decades, the rise of the “nones” has been interpreted as a threat and as an inevitable reckoning for corrupt and scandal-ridden institutions driving millions of people out of churches across the country.

Politics and social issues are hardly the only reasons, though they poll second in list from a 2017 Pew survey. At number one is “I question a lot of religious teachings,” at number three, the slightly more vague “I don’t like religious organizations.” It’s maybe a surprise that nonbelief in God appears all the way at number four. Which speaks to an important point.

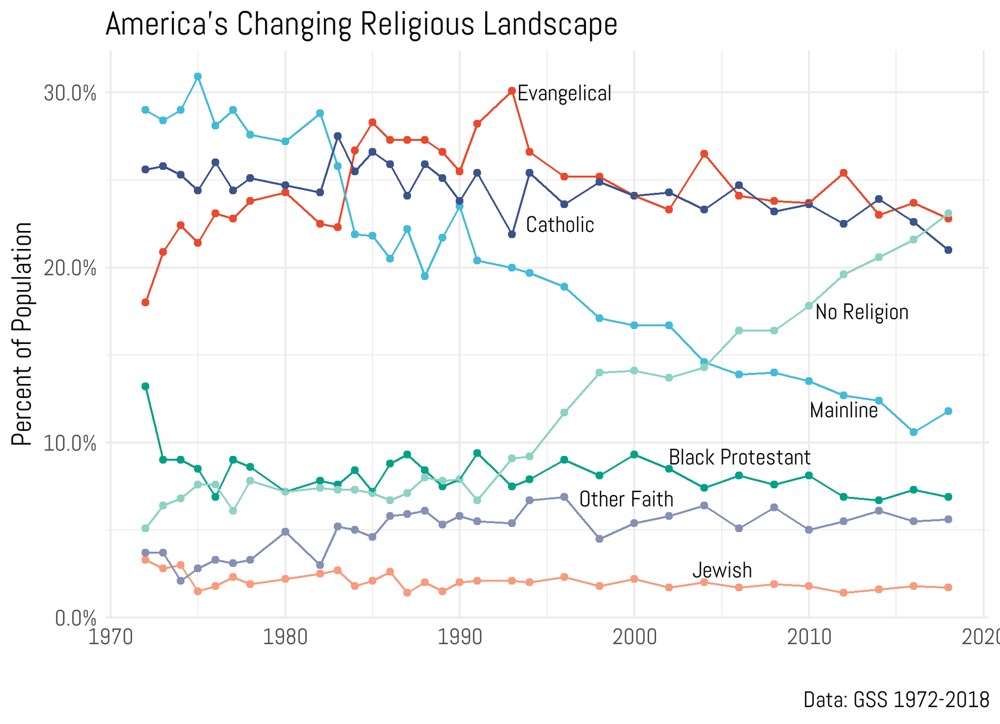

Not all of those exiting the pews have renounced their faith or converted to another, but huge numbers have joined the ranks of those who claim “no religion” in survey and polling data. Their numbers are now equivalent to Catholics and evangelicals, the two religious groups most in decline behind mainline Protestant churches. Political scientist Ryan P. Burge of Eastern Illinois University is not surprised. “It’s been a constant steady increase for 20 years now,” he says, pointing to data from a General Social Survey visualized in the graph above.

The last decade has seen the sharpest upturn yet, with “nones” now estimated at 23.1 percent of the population. If this rise—and subsequent plateaus and declines in the major religious groups surveyed (and the batch of non-Judeo-Christian “Other Faith”s dismissively lumped together)—continues, the shift could be dramatic. In 2014, 78% of the unaffiliated, according to Pew polling, were raised in and walked away from a religion. The shift in identity among young people tends to correlate with a shift in politics.

The “rising tide of religiously unaffiliated voters,” writes Jack Jenkins at Religion News Service, is “a group that a 2016 PRRI analysis found skews young and liberal.” It’s one that might offset the oversized influence of white evangelicals, who now make up 26% of the electorate and 22.5% of the population.

Any such conclusions should be drawn with several caveats. “Evangelicals punch way above their weight,” says Burge. “They turn out a bunch at the ballot box. That’s largely a function of the fact that they’re white and they’re old.” And, he might have added, many are in less economically precarious straits than their children and grandchildren, more susceptible to mass media messaging, and less prone, by design, to finding their vote suppressed. A 2016 PRRI report noted that “religiously unaffiliated Americans do not vote in the same percentages as evangelicals, and are often underrepresented at the polls.”

Additionally, and most importantly to point out any time these numbers come up: “the nones” is an entirely overdetermined category full of people who agree on little, but they’re not signing up for any church committees any time soon for a handful of loosely-related reasons. If herding atheists, only one part of this group, is like herding cats, trying to corral 23% of the population without any shared creed or specific ideology is corralling an even less predictable menagerie. We need to know far more about what people affirm, as well as what they deny, if we want a clearer picture of where the country’s politics—if not its government or policies—might be headed.

via Kottke

Related Content:

A Visual Map of the World’s Major Religions (and Non-Religions)

Animated Map Shows How the Five Major Religions Spread Across the World (3000 BC – 2000 AD)

Does Democracy Demand the Tolerance of the Intolerant? Karl Popper’s Paradox

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness