History remembers, and will likely never forget, the name of Renaissance Italian inventor Leonardo da Vinci. But what about the name of Renaissance Italian inventor Johannes de Fontana? Though he came along a couple of generations before Leonardo, Johannes de Fontana, also known as Giovanni Fontana, seems to have had no less fertile an imagination. Where Leonardo came up with everything from musical instruments to hydraulic pumps to war machines to self-supporting bridges, Fontana’s inventions include “fire-breathing automatons, pulley-powered angels, and the earliest surviving drawing of a magic lantern device.”

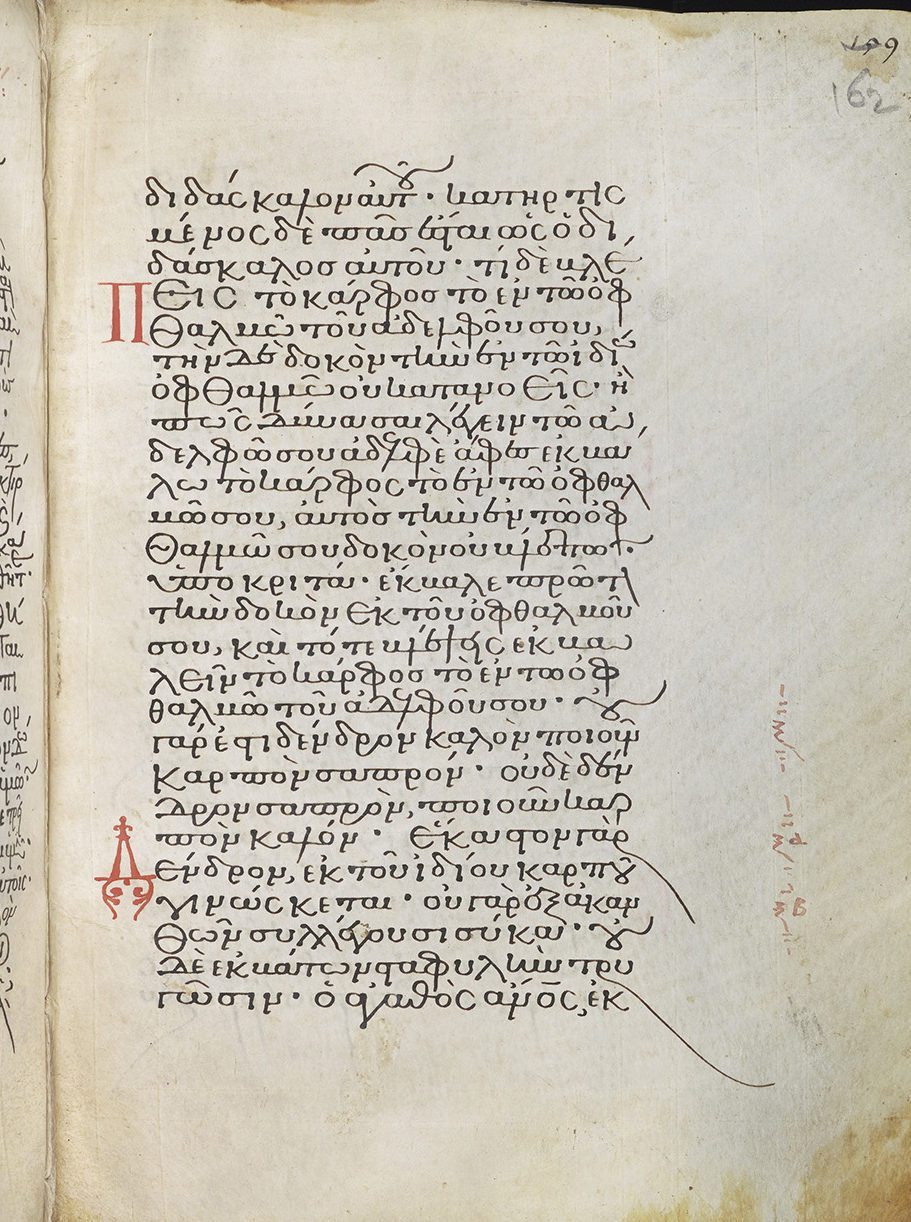

Those words come from Portland State University’s Bennett Gilbert, who takes a dive into Fontana’s notebook of “designs for a variety of fantastic and often impossible inventions” at the Public Domain Review.

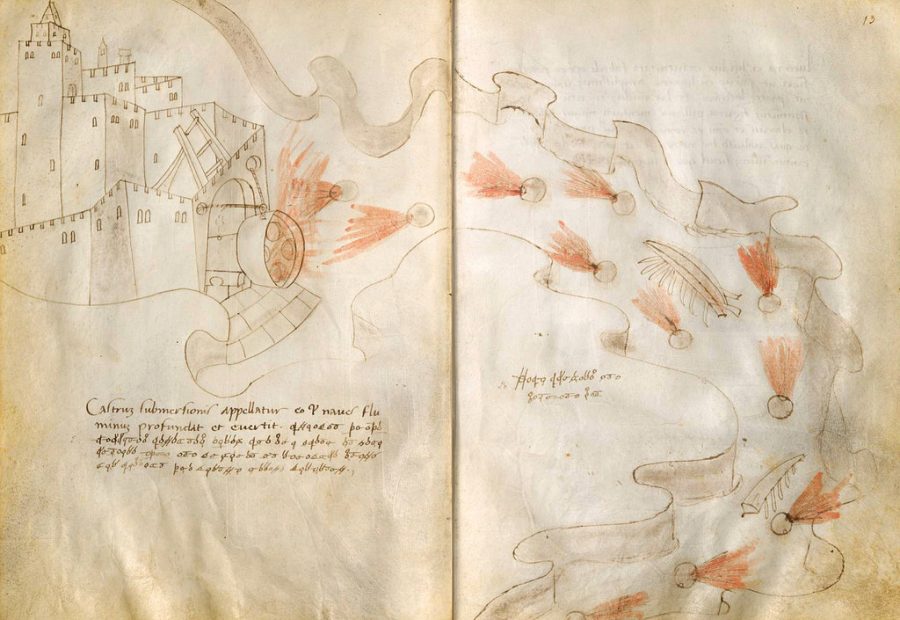

Filled some time between the years 1415 and 1420, its 68 drawings meant to entice potential patrons include plans for “mechanical camels for entertaining children, mysterious locks to guard treasure, flame-throwing contraptions to terrorize the defenders of besieged cities, huge fountains, musical instruments, actors’ masks, and many other wonders.”

It would seem that Fontana lacked the sense of practicality possessed by his successor Leonardo — and Leonardo dreamed up not just a variety of flying machines but a mechanical knight. That may have to do with the era in which Fontana lived, “more than two hundred years before the discoveries of Newton,” a time “of transition from medieval knowledge of the world to that of the Renaissance, which many now regard as the origin of early modern science.” And so his designs, many of them liberally decorated with unearthly-looking creatures and bursts of flame, strike us today as at most half plausible and at least half fantastical.

Fontana’s drawing style, too, reflects the state of human knowledge in the early fifteenth century: “The towers and rockets, water and fire, nozzles and pipes, pulleys and ropes, gears and grapples, wheels and beams, and grids and spheres that were an engineer’s occupation at the dawn of the Renaissance fill Fontana’s sketchbook. His way of illustrating his ideas, however, is distinctly medieval, lacking perspective and using a limited array of angles for displaying machine works.” Yet this makes Fontana’s notebook all the more fascinating to 21st-century eyes, and throws into contrast some of his more plausible inventions, such as “a magic lantern device, which transformed the light of fire into emotive display.”

Will some bold scholar of the early Renaissance one day argue that Fontana invented motion pictures? But perhaps the man who designed “an awe-inspiring fire-illuminated spectacle, most likely serving as a propaganda machine, for use in war and in peace” wouldn’t approve of a medium quite so ordinary. We might say that the most valuable legacy of Johannes de Fontana, more so than any of his inventions themselves, is the glimpse his notebook gives us into the the human imagination in his day, when fact and fantasy intermingled as they will never do again. And in the case of some technologies, we should probably feel relieved that they won’t: Fontana’s “life support system for patients undergoing gruesome surgeries” may be fascinating, but I can’t say I’d be eager to make use of it myself.

See his manuscript online here.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More

Buckminster Fuller Creates Striking Posters of His Own Inventions

Mark Twain’s Patented Inventions for Bra Straps and Other Everyday Items

The 10 Commandments of Chindōgu, the Japanese Art of Creating Unusually Useless Inventions

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.