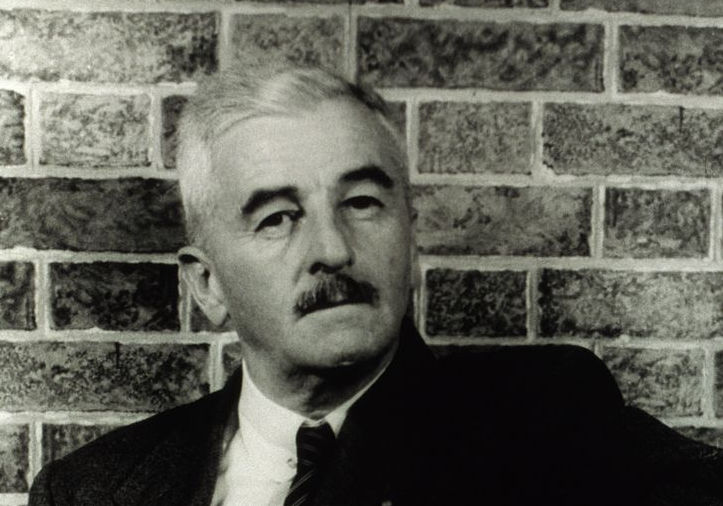

Image by Carl Van Vechten, via Wikimedia Commons

“How did Faulkner pull it off?” is a question many a fledgling writer has asked themselves while struggling through a period of apprenticeship like that novelist John Barth describes in his 1999 talk “My Faulkner.” Barth “reorchestrated” his literary heroes, he says, “in search of my writerly self… downloading my innumerable predecessors as only an insatiable green apprentice can.” Surely a great many writers can relate when Barth says, “it was Faulkner at his most involuted and incantatory who most enchanted me.” For many a writer, the Faulknerian sentence is an irresistible labyrinth. His syntax has a way of weaving itself into the unconscious, emerging as fair to middling imitation.

While studying at Johns Hopkins University, Barth found himself writing about his native Eastern Shore of Maryland in a pastiche style of “middle Faulkner and late Joyce.” He may have won some praise from a visiting young William Styron, “but the finished opus didn’t fly—for one thing, because Faulkner intimately knew his Snopses and Compsons and Sartorises, as I did not know my made-up denizens of the Maryland marsh.” The advice to write only what you know may not be worth much as a universal commandment. But studying the way that Faulkner wrote when he turned to the subjects he knew best provides an object lesson on how powerful a literary resource intimacy can be.

Not only does Faulkner’s deep affiliation with his characters’ inner lives elevate his portraits far above the level of local color or regionalist curiosity, but it animates his sentences, makes them constantly move and breathe. No matter how long and twisted they get, they do not wilt, wither, or drag; they run river-like, turning around in asides, outraging themselves and doubling and tripling back. Faulkner’s intimacy is not earnestness, it is the uncanny feeling of a raw encounter with a nerve center lighting up with information, all of it seemingly critically important.

It is the extraordinary sensory quality of his prose that enabled Faulkner to get away with writing the longest sentence in literature, at least according to the 1983 Guinness Book of World Records, a passage from Absalom, Absalom! consisting of 1,288 words and who knows how many different kinds of clauses. There are now longer sentences in English writing. Jonathan Coe’s The Rotter’s Club ends with a 33-page long whopper with 13,955 words in it. Entire novels hundreds of pages long have been written in one sentence in other languages. All of Faulkner’s modernist contemporaries, including of course Joyce, Woolf, and Beckett, mastered the use of run-ons, to different effect.

But, for a time, Faulkner took the run-on as far as it could go. He may have had no intention of inspiring postmodern fiction, but one of its best-known novelists, Barth, only found his voice by first writing a “heavily Faulknerian marsh-opera.” Many hundreds of experimental writers have had almost identical experiences trying to exorcise the Oxford, Mississippi modernist’s voice from their prose. Read that onetime longest sentence in literature, all 1,288 words of it, below.

Just exactly like Father if Father had known as much about it the night before I went out there as he did the day after I came back thinking Mad impotent old man who realized at last that there must be some limit even to the capabilities of a demon for doing harm, who must have seen his situation as that of the show girl, the pony, who realizes that the principal tune she prances to comes not from horn and fiddle and drum but from a clock and calendar, must have seen himself as the old wornout cannon which realizes that it can deliver just one more fierce shot and crumble to dust in its own furious blast and recoil, who looked about upon the scene which was still within his scope and compass and saw son gone, vanished, more insuperable to him now than if the son were dead since now (if the son still lived) his name would be different and those to call him by it strangers and whatever dragon’s outcropping of Sutpen blood the son might sow on the body of whatever strange woman would therefore carry on the tradition, accomplish the hereditary evil and harm under another name and upon and among people who will never have heard the right one; daughter doomed to spinsterhood who had chosen spinsterhood already before there was anyone named Charles Bon since the aunt who came to succor her in bereavement and sorrow found neither but instead that calm absolutely impenetrable face between a homespun dress and sunbonnet seen before a closed door and again in a cloudy swirl of chickens while Jones was building the coffin and which she wore during the next year while the aunt lived there and the three women wove their own garments and raised their own food and cut the wood they cooked it with (excusing what help they had from Jones who lived with his granddaughter in the abandoned fishing camp with its collapsing roof and rotting porch against which the rusty scythe which Sutpen was to lend him, make him borrow to cut away the weeds from the door-and at last forced him to use though not to cut weeds, at least not vegetable weeds ‑would lean for two years) and wore still after the aunt’s indignation had swept her back to town to live on stolen garden truck and out o f anonymous baskets left on her front steps at night, the three of them, the two daughters negro and white and the aunt twelve miles away watching from her distance as the two daughters watched from theirs the old demon, the ancient varicose and despairing Faustus fling his final main now with the Creditor’s hand already on his shoulder, running his little country store now for his bread and meat, haggling tediously over nickels and dimes with rapacious and poverty-stricken whites and negroes, who at one time could have galloped for ten miles in any direction without crossing his own boundary, using out of his meagre stock the cheap ribbons and beads and the stale violently-colored candy with which even an old man can seduce a fifteen-year-old country girl, to ruin the granddaughter o f his partner, this Jones-this gangling malaria-ridden white man whom he had given permission fourteen years ago to squat in the abandoned fishing camp with the year-old grandchild-Jones, partner porter and clerk who at the demon’s command removed with his own hand (and maybe delivered too) from the showcase the candy beads and ribbons, measured the very cloth from which Judith (who had not been bereaved and did not mourn) helped the granddaughter to fashion a dress to walk past the lounging men in, the side-looking and the tongues, until her increasing belly taught her embarrassment-or perhaps fear;-Jones who before ’61 had not even been allowed to approach the front of the house and who during the next four years got no nearer than the kitchen door and that only when he brought the game and fish and vegetables on which the seducer-to-be’s wife and daughter (and Clytie too, the one remaining servant, negro, the one who would forbid him to pass the kitchen door with what he brought) depended on to keep life in them, but who now entered the house itself on the (quite frequent now) afternoons when the demon would suddenly curse the store empty of customers and lock the door and repair to the rear and in the same tone in which he used to address his orderly or even his house servants when he had them (and in which he doubtless ordered Jones to fetch from the showcase the ribbons and beads and candy) direct Jones to fetch the jug, the two of them (and Jones even sitting now who in the old days, the old dead Sunday afternoons of monotonous peace which they spent beneath the scuppernong arbor in the back yard, the demon lying in the hammock while Jones squatted against a post, rising from time to time to pour for the demon from the demijohn and the bucket of spring water which he had fetched from the spring more than a mile away then squatting again, chortling and chuckling and saying ‘Sho, Mister Tawm’ each time the demon paused)-the two of them drinking turn and turn about from the jug and the demon not lying down now nor even sitting but reaching after the third or second drink that old man’s state of impotent and furious undefeat in which he would rise, swaying and plunging and shouting for his horse and pistols to ride single-handed into Washington and shoot Lincoln (a year or so too late here) and Sherman both, shouting, ‘Kill them! Shoot them down like the dogs they are!’ and Jones: ‘Sho, Kernel; sho now’ and catching him as he fell and commandeering the first passing wagon to take him to the house and carry him up the front steps and through the paintless formal door beneath its fanlight imported pane by pane from Europe which Judith held open for him to enter with no change, no alteration in that calm frozen face which she had worn for four years now, and on up the stairs and into the bedroom and put him to bed like a baby and then lie down himself on the floor beside the bed though not to sleep since before dawn the man on the bed would stir and groan and Jones would say, ‘flyer I am, Kernel. Hit’s all right. They aint whupped us yit, air they?’ this Jones who after the demon rode away with the regiment when the granddaughter was only eight years old would tell people that he ‘was lookin after Major’s place and niggers’ even before they had time to ask him why he was not with the troops and perhaps in time came to believe the lie himself, who was among the first to greet the demon when he returned, to meet him at the gate and say, ‘Well, Kernel, they kilt us but they aint whupped us yit, air they?’ who even worked, labored, sweat at the demon’s behest during that first furious period while the demon believed he could restore by sheer indomitable willing the Sutpen’s Hundred which he remembered and had lost, labored with no hope of pay or reward who must have seen long before the demon did (or would admit it) that the task was hopeless-blind Jones who apparently saw still in that furious lecherous wreck the old fine figure of the man who once galloped on the black thoroughbred about that domain two boundaries of which the eye could not see from any point.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

Related Content:

‘Never Be Afraid’: William Faulkner’s Speech to His Daughter’s Graduating Class in 1951

Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction

Rare 1952 Film: William Faulkner on His Native Soil in Oxford, Mississippi

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

If run-on stream-of-consciousness non-punctuated gimmick sentences are your cup of tea and I’m not suggesting that you or anyone around you is as easily susceptible to the allures presented by just such an arrangement but as the sun rises on a newly-minted day of seeming profound import while the birds are engaged well not so much engaged as oblivious to your presence but nonetheless providing a Greek chorus to accompany your thoughts to which your actions soon will be so well-suited then Faulkner’s sentence will provide you at intervals with little shrieks and squeals of delight.

Proust has a very long one near the beginning of A la recherche du temps perdu about nenuphars (water-lilies). Couldn’t be bothered to count them, though.

Supposedl, long sentences define the style of Proust. Is that his innovation ? What other characterisrics define his style ?

oh yeah? well I wrote a 1289 word sentence! Eat that Faulkner!

The humid, languid air, thick as sorghum syrup and clinging to the faded chintz of the porch swing where he sat, old man Witherspoon, his skin a roadmap of wrinkles tracing the long, meandering tributaries of a life spent mostly in the shade of the ancient oak, its branches gnarled and reaching like the arthritic fingers of time itself, a life, he thought, not unlike this sentence, stretching and twisting, burdened with clauses and qualifiers, a veritable caravan of subordinate thoughts lumbering across the dusty plains of narrative, a sentence, he mused, that, much like the elaborate and ostentatious displays of verbal dexterity he’d witnessed, nay, endured, in the latest literary journals, those pretentious tomes filled with the self-important pronouncements of writers who seemed to believe that the sheer length of their sentences was a testament to their profound understanding of the human condition, when in reality, he suspected, it was merely a symptom of their inability to edit, or perhaps, a desperate, almost pathetic, attempt to mask the hollowness of their ideas beneath a thick, impenetrable fog of verbiage, a fog, he thought, not unlike the one that often rolled in from the river, obscuring the familiar landscape, blurring the lines between reality and illusion, much as these sprawling, labyrinthine sentences obscured the simple truth that a story, a truly compelling story, was not a matter of linguistic gymnastics or rhetorical acrobatics, but rather, a matter of capturing the essence of human experience, the raw, unfiltered emotions that pulsed beneath the surface of everyday life, the unspoken desires, the hidden fears, the quiet desperation that gnawed at the edges of consciousness, those fleeting moments of epiphany that illuminated the darkness, those subtle nuances of human interaction that revealed the intricate tapestry of relationships, the delicate balance between love and hate, joy and sorrow, hope and despair, all of which, he believed, could be conveyed with far greater clarity and impact through the judicious use of concise, evocative language, through the careful selection of words that resonated with meaning, through the strategic deployment of punctuation that guided the reader through the emotional landscape of the narrative, instead of these endless, meandering streams of consciousness, these verbal rivers that flowed aimlessly, carrying with them a cargo of extraneous details and irrelevant observations, a cargo, he thought, like the flotsam and jetsam that washed up on the riverbank after a storm, a collection of random objects, devoid of any intrinsic value, yet presented as if they were precious artifacts, worthy of careful examination, these sentences, he thought, were like those elaborate, multi-tiered cakes that were all frosting and no substance, a sugary facade that concealed a hollow core, a testament to the baker’s skill in decoration, perhaps, but not to their ability to create a truly satisfying culinary experience, and he, old man Witherspoon, who had spent a lifetime observing the ebb and flow of human existence, who had witnessed the rise and fall of fortunes, the triumphs and tragedies of his fellow man, who had learned to appreciate the beauty of simplicity, the power of understatement, the eloquence of silence, he, with a sigh as deep as the roots of the ancient oak, could not help but wonder if these writers, these purveyors of verbose prose, these architects of convoluted sentences, ever paused to consider the reader, the poor, beleaguered reader, who was forced to navigate this dense thicket of words, this tangled web of clauses and phrases, this endless, meandering journey through the author’s mind, a journey, he imagined, much like trying to find a lost button in a haystack, a futile and frustrating endeavor, a task that required an inordinate amount of patience and perseverance, a task that ultimately yielded little reward, and he, old man Witherspoon, with a weary shake of his head, resolved to return to his well-worn copy of “The Old Man and the Sea,” a slim volume, a masterpiece of concision, a testament to the power of Hemingway’s minimalist prose, a reminder that true artistry lay not in the quantity of words, but in the quality of their arrangement, in the ability to distill the essence of human experience into its purest form, to capture the heart of the matter with a single, perfectly crafted sentence, a sentence that resonated with truth, a sentence that lingered in the mind long after the book was closed, a sentence, unlike this one, that knew when to stop, before it became a parody of itself, a self-indulgent exercise in linguistic excess, a monument to the writer’s ego, a testament to the vanity of words, a sentence, in short, that knew that sometimes, less was indeed more, and that the greatest stories were often told in the simplest of terms, a thought, he realized, that was itself far too long winded.

I’m a teacher. A run on sentence is a run on sentence. Just because he’s a famous writer does not give liberty to disregard certain rules of grammar to accommodate his writing whimsy.

what about Molly Blooms multi-page rant at the end of Ulysses ? waaay more words than this.

rules be da#*d ! long sentences can better convey the urgency of a situation, panic, mania. they may be rough on the reader, but imagine being the character in that state of agitation or euphoria

Oh, heck, I hand wrote one continuous sentence three pages long for my Methods of Ed mid-term eons ago. I thought it would piss off my professor which was my aim (I don’t remember why). I got the test back marked “creative” and an “A.” I remember being disappointed that I didn’t get the rise out of my professor I was after. Learned not to let student stunts get the better of me from that man.

Patent claims must be a single sentence. The longest one I am aware of has over 17000 words (U.S. Patent No. 6,953,802). These are often chemistry patents where a core structure is invented and then the lawyers and chemists then list every possible thing you could reasonably attach at every possible point.

Yes it does. A writer is like an artist. There are no rules. He is undoubtedly the greatest American novelist of our time.

Should there be rules for poets? Of course not. What is the difference? If this ‘gets under your skin’ don’t read him.

Faulkner never graduated from high school nor earned a college degree. He worked in the coal mines using his breaks to write.

Quite an accomplishment in my opinion.

It is truly aswsome

So what Faulkner wrote was a run-on sentence?