The legend of Queen is immortal. It needs no further burnishing, not even, some might argue, by the most recent Oscar-winning biopic. The film may gamely recreate the stagecraft of Britain’s most operatic export. But once you’ve seen the real thing, what need of a substitute? For the millions who loved them before Wayne’s World brought them back to global consciousness, and the millions who came to love them afterward, the only thing that could be better than watching live Queen is watching more live Queen.

If you’re one of those millions, you’ll thrill at this concert film of Queen live in Montreal in 1981, “at their near peak,” writes Twisted Sifter. The footage you see here has been lovingly restored from an original release that chopped two different nights’ performances together in a hash the band hated.

The restoration, as Brian May himself explained in 2007, is now “much much more true to what actually happened at any given moment…. And I do find that once I’m five minutes into the film, I’m caught up in it as a real live show.” It is, he says, “a great piece of work.”

Directed by Saul Swimmer, the documentarian who made George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, the film was plagued by misunderstanding and hostility, as May describes it. Freddie Mercury hated the experience and the director. “What you will see,” says the guitarist, “is a very edgy, angry band, carving out a performance in a rather uncomfortable situation.” But what performances they are. “High energy, real, and raw.”

Yet no justice was done to the electric rage they brought to the stage those two nights. The film was shot on very high-quality 35mm, then very badly edited with poor attempts at matching sound and video from different performances. In 1984, an even worse VHS version titled We Will Rock You appeared, then it went to DVD in 2001. The band protested but could only remedy the situation when they bought the rights to the film.

In describing the restoration process, May, the irrepressible scientist, gets most excited:

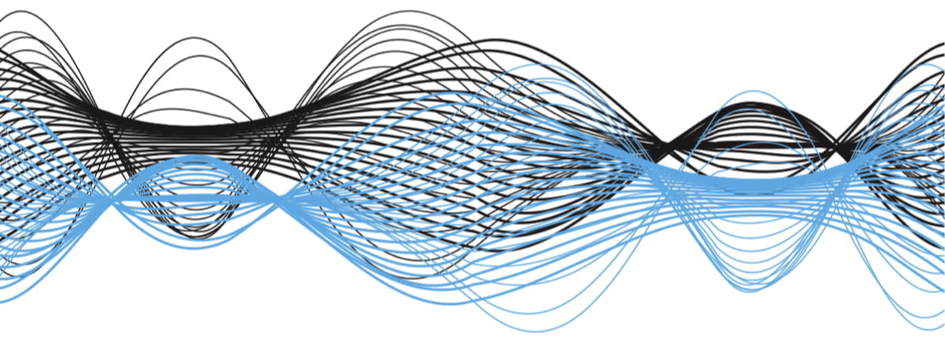

The surviving negative went to be doctored in the USA – by a process using algorithms invented by John D Lowry of NASA for rescuing the film from the Apollo Moon missions. (Astrophysics gets everywhere!) You know how quick computers are these days…? Well, to give you an idea of the huge number-crunching involved, it took 700 Apple Mac G5’s one MONTH to process this film.

From the original 24-track audio, all the songs, which had been edited, were restored to their full length, and what footage wasn’t cut and discarded was rejoined “with modern digital artistry” into full performances.

Given that the outtakes had disappeared, the result “is a document which concentrates on Freddie,” says May, but no one in the band “is upset” about that. I doubt any Queen fans will be overly upset either. See and hear the gloriously restored film and live audio from Montreal in 1981 here: a fast version of “We Will Rock You,” “Somebody to Love,” “Killer Queen,” “Bohemian Rhapsody,” “Another One Bites the Dust,” the slow version of “We Will Rock You,” and “We Are the Champions,” below.

via Twisted Sifter

Related Content:

Scenes from Bohemian Rhapsody Compared to Real Life: A 21-Minute Compilation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness