Enjoy, but the rule is once you start, you have to listen through to the very, very end. :)

Enjoy, but the rule is once you start, you have to listen through to the very, very end. :)

This past fall, Stanford Continuing Studies and the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships teamed up to offer an important course on the challenges facing journalism and the freedom of the press. Called Journalism Under Siege? Truth and Trust in a Time of Turmoil, the five-week course featured 28 journalists and media experts, all offering insights on the emerging challenges facing the media across the United States and the wider world. The lectures/presentations are now all online. Find them below, along with the list of guest speakers, which includes Alex Stamos who blew the whistle on Russia’s manipulation of the Facebook platform during the 2016 election. Journalism Under Siege will be added to our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Weekly Sessions:

Guest Speakers:

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Seder-Masochism, copyright abolitionist Nina Paley’s latest animated release, is guaranteed to ruffle feathers in certain quarters, though the last laugh belongs to this trickster artist, who shares writing credit with ”God, Moses or a series of patriarchal males, depending on who you ask.”

Bypassing a commercial release in favor of the public domain goes a long way toward inoculating the film and its creator against expensive rights issues that could arise from the star-studded soundtrack.

It also lets the air out of any affronted parties’ campaigns for mass box office boycotts.

“The criticism seems equally divided between people that say I’m a Zionist and people that say I’m an anti-Zionist,” Paley says of This Land Is Mine, below, a stunning sequence of tribal and inter-tribal carnage, memorably set to Ernest Gold’s theme for the 1960 epic Paul Newman vehicle, Exodus.

Released as a stand-alone short, This Land Is Mine has become the most viewed of Paley’s works. She finds the opposing camps’ equal outcry encouraging, proof that she’s doing “something right.”

More bothersome has been University of Illinois Associate Professor of Gender Studies Mimi Thi Nguyen’s social media push to brand the filmmaker as transphobic. (Paley, no fan of identity politics, states that her “crime was, months earlier, sharing on Facebook the following lyric: ‘If a person has a penis he’s a man.’”) Nguyen’s actions resulted in the feminist film’s ouster from several venues and festivals, including Ebertfest in Paley’s hometown and a women’s film festival in Belgium.

What would the ancient fertility goddesses populating both art history and Seder-Masochism have to say about that development?

In Seder-Masochism, these goddess figures, whom Paley earlier transformed into a series of free downloadable GIFs, offer a mostly silent rebuke to those who refuse to acknowledge any conception of the divine existing outside patriarchal tradition.

In the case of Assistant Professor Nguyen, perhaps the goddesses would err on the side of diplomacy (and the First Amendment), framing the dust-up as just one more reason the public should be glad the project’s lodged in the public domain. Anyone with access to the Internet and a desire to see the film will have the opportunity to do so. Called out, maybe. Shut down, never.

The goddesses supply a depth of meaning to this largely comic undertaking. Their ample curves inform many of the patterns that give motion to the animated cutouts.

Paley also gets a lot of mileage from replicating supernumerary characters until they march with ant-like purpose or bedazzle in Busby Berkeley-style spectacles. Not since Paul Mazursky’s Tempest have goats loomed so large in cinematic choreography…

Paley’s use of music is another source of abiding pleasure. She casts a wide net—punk, disco, Bulgarian folk, the Beatles, Free to Be You and Me—again, framing her choices as parody. “Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here” accompanies the seventh plague of Egypt (don’t bother looking it up. It’s hail.) Ringo Starr’s famous “Helter Skelter” aside (“I’ve got blisters on my fingers!”) boils down to an apt choice for plague number six. (If you have to think about it…)

The elements of the Seder plate are listed to the strains of “Tijuana Taxi” because… well, who doesn’t love Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass?

Paley’s own religious background is of obvious interest here, and as with her previous feature, Sita Sings the Blues—also in the public domain—the autobiographical element is irresistible. A 2011 audio recording provides the excuse to portray her father, Hiram, who died the year after the interview was conducted, as a Monty Python-esque God. The senior Paley was raised in an observant Jewish household, but lost faith as a young man. An atheist who wanted his children to know something of their heritage, Passover was the one Jewish holiday he continued to celebrate. (He also forbade the kids from participating in any sort of secular Christmas activities.)

A wistful God with the complexion of a dollar bill, Hiram is at times surrounded by putti, in the form of his parents, his contentious Uncle Herschel, and his own sweet younger self.

For these scenes, Paley portrays herself as a spirited “sacrificial goat.” This character finds an echo at film’s end, when “Chad Gadya,” the traditional Passover tune that brings the annual seder to a rollicking conclusion, is brought to life using embroidermation, a form Paley may or may not have invented.

Perhaps Paley’s most subversive joke is choosing Jesus, as depicted in Juan de Juanes’ 1652 painting, The Last Supper, to deliver an educational blow-by-blow of Passover ritual.

Actually, much like Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady and Natalie Wood in West Side Story, Jesus was ghost-voiced by another performer—Barry Gray, narrator of the midcentury educational recording The Moishe Oysher Seder.

As you may have gleaned, Paley, despite the clean elegance of her animated line, is a maximalist. There’s something for everyone (excepting, of course, Mimi Thi Nguyen)—a gleaming golden idol, a ball bouncing above hieroglyphic lyrics, actual footage of atrocities committed in a state of religious fervor, Moses’ brother Aaron—a figure who’s often shoved to the sidelines, if not left outright on the cutting room floor.

We leave you with Paley’s prayer to her Muse, found freely shared on her website:

Our Idea

Which art in the Ether

That cannot be named;

Thy Vision come

Thy Will be done

On Earth, as it is in Abstraction.

Give us this day our daily Spark

And forgive us our criticisms

As we forgive those who critique against us;

And lead us not into stagnation

But deliver us from Ego;

For Thine is the Vision

And the Power

And the Glory forever.

Amen.

Watch Seder-Masochism in its entirety up top, or download it here. Purchase the companion book here.

Related Content:

Sita Sings the Blues Now on YouTube

Watch Nina Paley’s “Embroidermation,” a New, Stunningly Labor-Intensive Form of Animation

Introduction to the Old Testament: A Free Yale Course

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain, this April. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

It has been a season of mourning for literature: first the death of Mary Oliver and now W.S. Merwin, two writers who left a considerable imprint on over half a century of American poetry. Considering the fact that founding father of the Beats and proprietor of world-renowned City Lights Bookstore, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, turns 100 on March 24th, maybe a few more people have glanced over to check on him. How’s he doing?

He’s grown “frail and nearly blind,” writes Chloe Veltman at The Guardian in an interview with the poet this month, “but his mind is still on fire.” Ferlinghetti “has not mellowed,” says Washington Post book critic Ron Charles, “at all.” If you’re looking for him at any of the events planned in his honor, City Lights announces, he will not be in attendance, but he has been busy promoting his latest book, a thinly-veiled autobiographical novel about his early life called Little Boy.

In the book Ferlinghetti describes his childhood in images right out of Edward Gorey. He was a “Little Lord Fauntleroy” in a Bronxville mansion 20 miles outside New York, an orphan taken in and raised by descendants of the founders of Sarah Lawrence. “His new guardians spoke to one another in courtly tones and dressed in Victorian garb,” notes Charles. “They sent him to private school, and, more important, they possessed a fine library, which he was encouraged to use.”

The poet would later write he was a “social climber climbing downward,” an ironic reference to how some people might have seen the trajectory of his career. After serving in the Navy during World War II, earning a master’s at Columbia, and a Ph.D. at the Sorbonne, Ferlinghetti decamped to San Francisco, and founded the small magazine City Lights with Peter D. Martin. Then he opened a bookstore on the edge of Chinatown to fund the publishing venture.

The shop became a haunt for writers and poets. Ferlinghetti started publishing them, starting with himself in 1955. The following year he gained international infamy for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (hear Ginsberg read the poem in ’56). The book was banned, and Ferlinghetti put on trial for obscenity. If anyone thought this would be the end of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, they were mistaken.

He has published somewhere around forty books of poetry and criticism, novels and plays, been a prolific painter for sixty years, as well as a publisher, bookseller, and activist. He does not consider himself a Beat poet, but from his influential first two books—Pictures of the Gone World and 1958’s A Coney Island of the Mind—onward, Ferlinghetti’s philosophical outlook has more or less breathed the same air as Ginsberg et al.’s.

Quoting from Coney Island, Andrew Shapiro writes, “he counseled us to ‘confound the system,’ ‘to empty out our pockets… missing our appointments’ and to leave ‘our neckties behind’ and ‘take up the full beard of walking anarchy.’” He is still doing this, every way that he can, in public readings, media appearances, and a canny use of YouTube. His is not a call to flower power but to full immersion in the chaos of life, or, as he writes in “Coney Island of the Mind 1” in the “veritable rage / of adversity / Heaped up / groaning with babies and bayonets / under cement skies / in an abstract landscape of blasted trees.”

Ferlinghetti urged poets and writers to “create works capable of answering the challenge of apocalyptic times, even if this meaning sounds apocalyptic… you can conquer the conquerors with words.” Despite this stridency, he has never taken himself too seriously. Ferlinghetti is as relaxed as they come—he hasn’t mellowed, but he also hasn’t needed to. He’s a loose, natural storyteller and comedian and he’s still delivering sober, prophetic pronouncements with gravitas.

See and hear Ferlinghetti take on conquerors, bullies, and xenophobes, underwear, and other subjects in the readings here from his throughout his career, including a full, 40-minute reading in 2005 at UC Berkeley, below, an album of Ferlinghetti and Kenneth Rexroth, above, and at the top, a video made last year of the 99-year-old poet, in Lady Liberty mask, reading “Trump’s Trojan Horse” under a grinning, gray-bearded self-portrait of his younger self. Happy 100th to him. “I figure that with another 100 birthdays,” he says, “that’ll be about enough!”

Related Content:

The First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading “Howl” (1956)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

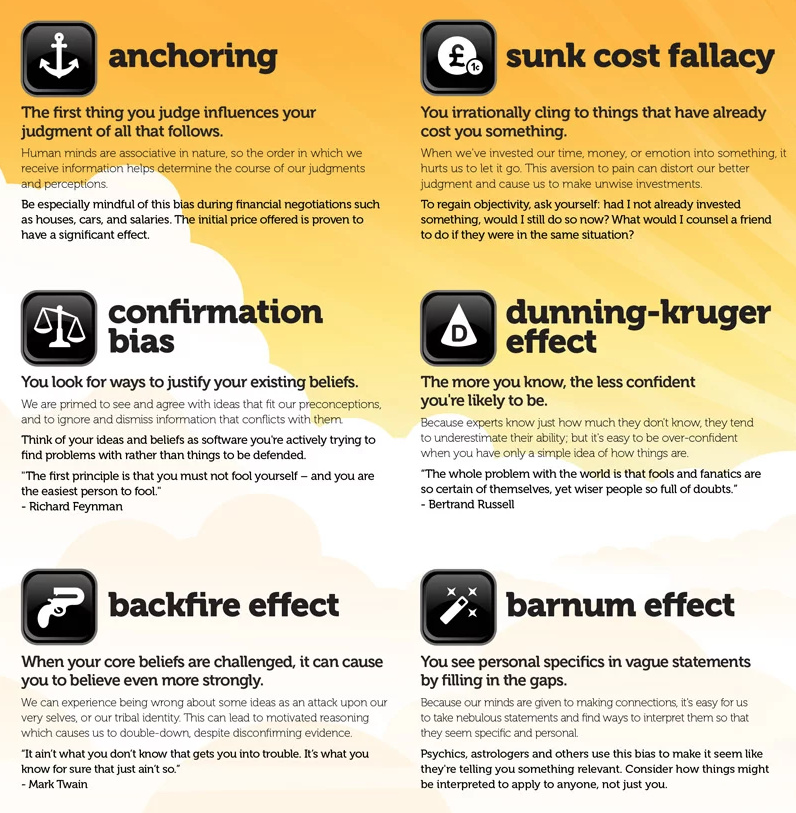

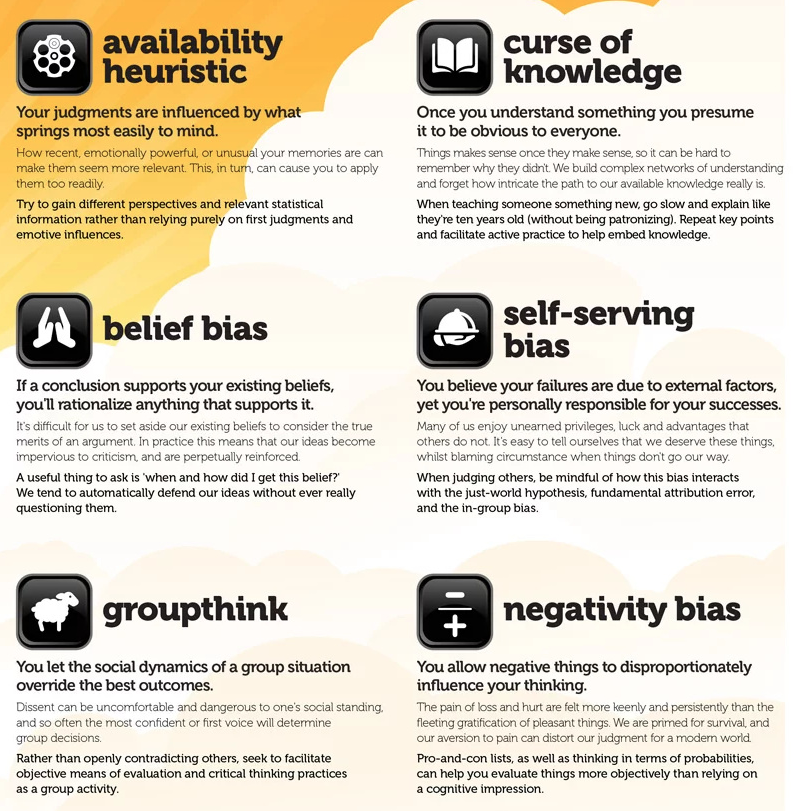

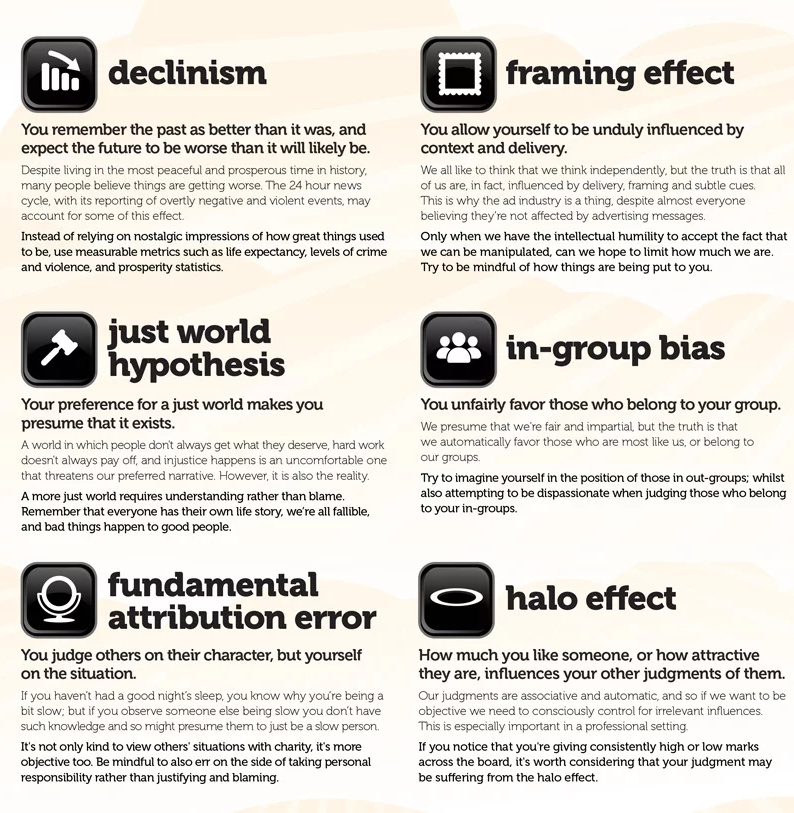

There’s been a lot of talk about the Dunning-Kruger effect, the cognitive bias that makes people wildly overconfident, unable to know how ignorant they are because they don’t have the basic skills to grasp what competence means. Once popularized, the effect became weaponized. People made armchair diagnoses, gloated and pointed at the obliviously stupid. But if those finger-pointers could take the beam out of their own eye, they might see four fingers pointing back at them, or whatever folk wisdom to this effect you care to mash up.

What we now call cognitive biases have been known by many other names over the course of millennia. Perhaps never have the many varieties of self-deception been so specific. Wikipedia lists 185 cognitive biases, 185 different ways of being irrational and deluded. Surely, it’s possible that every single time we—maybe accurately—point out someone else’s delusions, we’re hoarding a collection of our own. According to much of the research by psychologists and behavioral economists, this may be inevitable and almost impossible to remedy.

Granted, a Wikipedia list is a crowd-sourced creation with lots of redundancy and quite a few “dubious or trivial” entries, writes Ben Yagoda at The Atlantic. “The IKEA effect, for instance, is defined as ‘the tendency for people to place a disproportionately high value on objects they partially assembled themselves.’” Much of the value I’ve personally placed on IKEA furniture has to do with never wanting to assemble IKEA furniture again. “But a solid group of 100 or so biases has been repeatedly shown to exist, and can make a hash of our lives.”

These are the tricks of the mind that keep gamblers gambling, even when they’re losing everything. They include not only the “gambler’s fallacy” but confirmation bias and the fallacy of sunk cost, the tendency to pursue a bad outcome because you’ve already made a significant investment and you don’t want it to have been for nothing. It may seem ironic that the study of cognitive biases developed primarily in the field of economics, the only social science, perhaps, that still assumes humans are autonomous individuals who freely make rational choices.

But then, economists must constantly contend with the counter-evidence—rationality is not a thing most humans do well. (Evolutionarily speaking, this may have been no great disadvantage until we got our hands on weapons of mass destruction and the tools of climate collapse.) When we act rationally in some areas, we tend to fool ourselves in others. Is it possible to overcome bias? That depends on what we mean. Political and personal prejudices—against ethnicities, nationalities, genders, and sexualities—are usually buttressed by the systems errors known as cognitive biases, but they are not caused by them. They are learned ideas that can be unlearned.

What researchers and academics mean when they talk about bias does not relate to specific content of beliefs, but rather to the ways in which our minds warp logic to serve some psychological or emotional need or to help regulate and stabilize our perceptions in a manageable way. “Some of these biases are related to memory,” writes Kendra Cherry at Very Well Mind, others “might be related to problems with attention. Since attention is a limited resource, people have to be selective about what they pay attention to in the world around them.”

We’re constantly missing what’s right in front of us, in other words, because we’re trying to pay attention to other people too. It’s exhausting, which might be why we need eight hours or so of sleep each night if we want our brains to function half decently. Go to yourbias.is for this list of 24 common cognitive biases, also available on a nifty poster you can order and hang on the wall. You’ll also find there an illustrated collection of logical fallacies and a set of “critical thinking cards” featuring both kinds of reasoning errors. Once you’ve identified and defeated all your own cognitive biases—all 24, or 100, or 185 or so—then you’ll be ready to set out and fix everyone else’s.

Related Content:

The Power of Empathy: A Quick Animated Lesson That Can Make You a Better Person

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

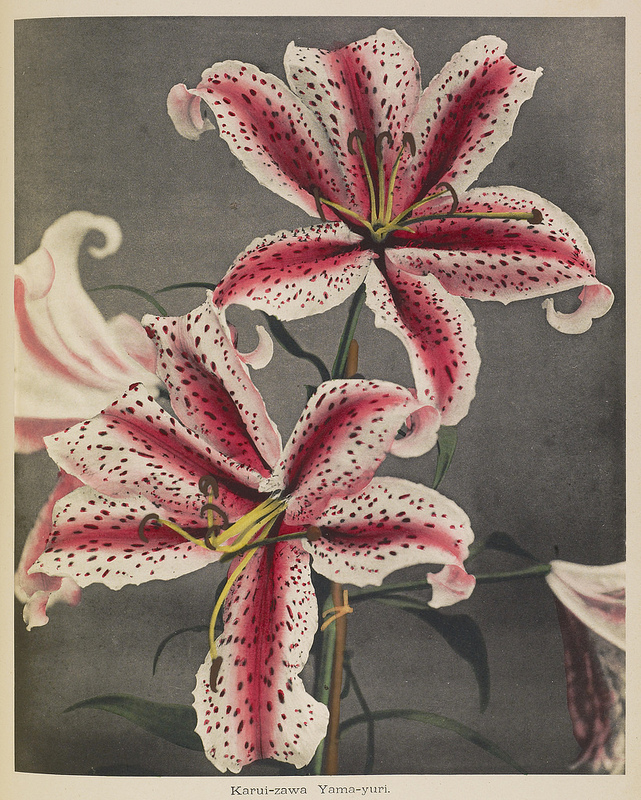

Ogawa Kazumasa lived from the 1860s to almost the 1930s, surely one of the most fascinating 70-year stretches in Japanese history. Ogawa’s homeland “opened” to the world when he was a boy, and for the rest of his life he bore witness to the sometimes beautiful, sometimes strange, sometimes exhilarating results of a once-isolated culture assimilating seemingly everything foreign — art, technology, customs — all at once. Naturally he picked up a camera to document it all, and history now remembers him as a pioneer of his art.

At the Getty’s web site you can see a few examples of the sort of pictures Ogawa took of Japanese life in the mid-1890s. During that same period he published Some Japanese Flowers, a book containing his pictures of just that.

The following year, Ogawa’s hand-colored photographs of Japanese flowers also appeared in the American books Japan, Described and Illustrated by the Japanese, edited by the renowned Anglo-Irish expatriate Japanese culture scholar Francis Brinkley and published in Boston, the city where Ogawa had spent a couple of years studying portrait photography and processing.

Ogawa’s varied life in Japan included working as an editor at Shashin Shinpō (写真新報), the only photography journal in the country at the time, as well as at the flower magazine Kokka (国華), which would certainly have given him the experience he needed to produce photographic specimens such as these. Though Ogawa invested a great deal in learning and employing the highest photographic technologies, they were the highest photographic technologies of the 1890s, when color photography necessitated adding colors — of particular importance in the case of flowers — after the fact.

Some Japanese Flowers was re-issued a few years ago, but you can still see 20 striking examples of Ogawa’s flower photography at the Public Domain Review. They’ve also made several of his works available as prints of several different sizes in their online shop, a selection that includes not just his flowers but the Bronze Buddha at Kamakura and a man locked in battle with an octopus as well. Even as everything changed so rapidly all around him, as he mastered the just-as-rapidly developing tools of his craft, Ogawa nevertheless kept his eye for the natural and cultural aspects of his homeland that seemed never to have changed at all.

Related Content:

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

How Obsessive Artists Colorize Old Photographs & Restore the True Colors of the Past

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Ancient Greece and Rome have provided fertile hunting grounds for animated subject matter since the very inception of the form.

So what if the results wind up doing little more than frolic in the pastoral setting? Witness 1930’s Playful Pan, above, which can basically be summed up as Silly Symphony in a toga (with a cute bear cub who looks a lot like Mickey Mouse and some flame play that prefigures The Sorcerer’s Apprentice…)

Others are packed with history, mythic narrative, and period details, though be forewarned that not all are as visually appealing as Steve Simons’ Hoplites! Greeks at War, part of the Panoply Vase Animation Project.

Some series, such as the Asterix movies and Aesop and Son—a staple of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show from 1959 to 1962—have been the gateways through which many history lovers’ curiosity was first roused.

(Russian animator Anatoly Petrov’s erotic shorts for Soyuzmultfilm may rouse other, er, curiosities, and are definitely NSFW.)

And then there are instant classics like 2004’s It’s All Greek to Scooby in which “Shaggy’s purchase of a mysterious amulet only serves to cause a pestering archaeologist and centaur to chase him.” (Ye gods…)

Senior Lecturer of Classical and Mediterranean Studies at Vanderbilt, Chiara Sulprizio, has collected all of these and more on her blog, Animated Antiquity.

Beginning with the 2‑minute fragment that’s all we have left of Winsor McCay’s 1921 The Centaurs, Sulprizio shares some of her favorite cartoon representations of ancient Greece, Rome, and beyond. Her areas of professional specialization—gender and sexuality, Greek comedy, and Roman satire—are well suited to her chosen hobby, and her commentary doubles down on historical context to include the history of animation.

The appearance of cartoon stars like Daffy Duck, Tom and Jerry, and Popeye further demonstrates this antique subject matter’s sturdiness. TED-Ed and the BBC may view the genre as an excellent teaching tool, but there’s nothing stopping the animator from shoehorning some fabrications in amongst the buxom nymphs and buff gladiators.

(Raise your hand if your mother ever sacrificed you on the altar to Spinachia, goddess of spinach, in hopes that she might unleash a mushroom cloud of super-atomic power in your puny bicep.)

You’ll find a number of entries featuring the work of Japanese and Russian animators, including Thermae Romae, part of the juggernaut that’s sprung from Mari Yamazaki’s popular graphic novel series and Icarus and the Wise Men from the legendary Fyodor Khitruk, whose retelling of the myth sent a message about freedom from the Soviet Union, circa 1976.

Begin your decade-by-decade explorations of Chiara Sulprizio’s animated antiquities here or suggest that a missing favorite be added to the collection. (We vote for this one!)

Related Content:

Watch Art on Ancient Greek Vases Come to Life with 21st Century Animation

18 Classic Myths Explained with Animation: Pandora’s Box, Sisyphus & More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain, this April. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

I’ve had Trout Mask Replica in my collection for years. I can’t say I regularly pull it out to give it a listen, but I know I’d never get rid of it. It’s a sometimes impenetrable slab of genius, wrought from endless sessions and then a short burst of recording, led by a man who couldn’t read music, was prone to fits of violent anger, but dammit knew what he wanted. (And Zappa produced.) When I learned later that the house where a lot of this went down was located in the hills behind the suburbs of Woodland Hills, it made the insurrection of the album all the more magical.

But yes, it’s a hard one to get into. There are no “hits.” There’s no foot tappin’ pop (well, mayyyyybe “Ella Guru,” and only because I knew it first as a cover by XTC.) It’s discordant. Don Van Vliet aka Captain Beefheart sounds possessed by Howlin’ Wolf trying to sing nursery rhymes on acid, and it often plays like members of the band are in different areas of the house with a vague idea of what the others are doing. (This is actually a bit close to the truth).

Vox’s continuing series “Earworm,” hosted by Estelle Caswell, attempts to convert listeners who may have never heard of the album, by taking apart the opening track, “Frownland.”

As Caswell explains, with help from musicologists Samuel Andreyev and Susan Rogers, Van Vliet melded blues and free jazz, and played it with a deconstructed rock band instrumentation. Drums and bass did not lock down a rhythm–they played independent of the others, with the bass even playing chords. Rhythm and lead guitar played two different time signatures each, and neither were easy, 4/4 rhythms. And then there’s the saxophone work, dropping in to squonk and thrash like Ornette Coleman. As Magic Band members point out, Van Vliet didn’t understand that a bass or a guitar did not have the same range of notes as an 88-key piano, which was Van Vliet’s songwriting instrument.

However, only jazzbos dig on learning about polyrhythms. There’s so many other reasons to appreciate Trout Mask. For one, it’s in the proud tradition of European surrealism but also comes from a particular “old weird America” that produced some of our most brilliant nutcases. (How many people, learning that Van Vliet was raised near Joshua Tree, nodded in enlightenment? Of course he was.) You want drug music, the album says…well then, this is the uncut stuff.

And then sometimes it really just hits hard: “Moonlight On Vermont” is relentless, with a corruscating guitar line and Beefheart worked up into a lather over “that old time religion.” He quotes Blind Willie Johnson, conflates paganism and Puritanism, and transcends both. (Maybe this is the gateway song for newbies?)

The Vox video precedes its defense with some negative reviews from the contemporary press, but this Dick Larson review from the time understood it from the get go, who writes about it as a giant step forward after Beefheart’s two previous, more accessible albums:

Dylan would sympathise with Beefheart’s ‘nature-and-love-trips’, but the Captain is faster and more bulbous (and he’s got his band). But this is it. In straightening out his music, he’s found some kind of religion. It may be in hair pies (yes!) or in Frownland, but mainly it’s people, children and country men and women. And this is a new delight for Beefheart – a rough outdoor humanity blended with humour and a rich verbal vomit of imagery.

It is a wild album, literally. There are field recordings in between the music, with sounds of crickets and a plane passing overhead. The LP art shows the band standing, crouching, and hiding in the overgrown backyard of the house. There’s mysterious things in the stream below and only some of them are fish.

Related Content:

Tom Waits Makes a List of His Top 20 Favorite Albums of All Time

Hear a Rare Poetry Reading by Captain Beefheart (1993)

Captain Beefheart Issues His “Ten Commandments of Guitar Playing”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.