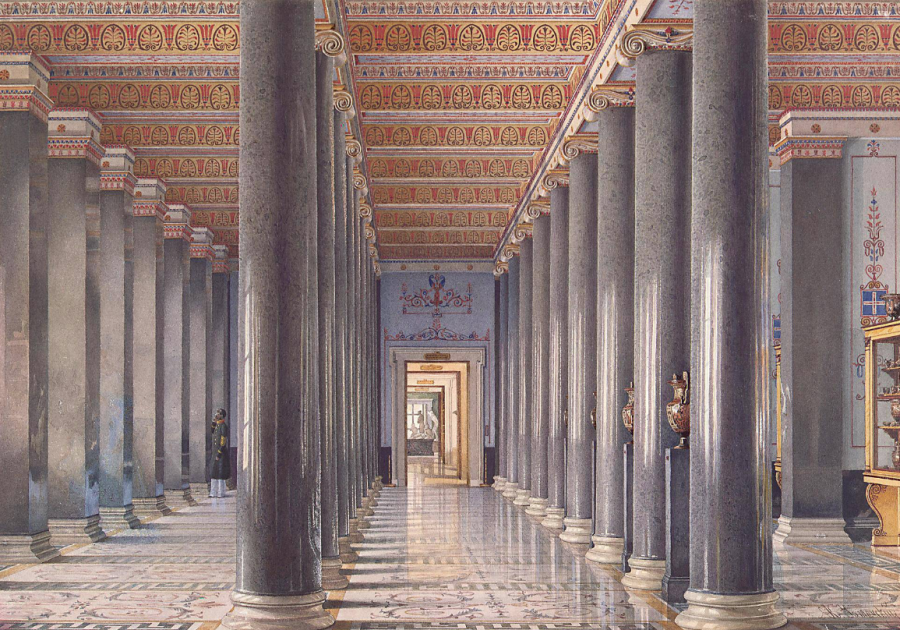

Along with hundreds of other seaside cities, island towns, and entire islands, historic Venice, the floating city, may soon sink beneath the waves if sea levels continue their rapid rise. The city is slowly tilting to the East and has seen historic floods inundate over 70 percent of its palazzo- and basilica-lined streets. But should such tragic losses come to pass, we’ll still have Venice, or a digital version of it, at least—one that aggregates 1,000 years of art, architecture, and “mundane paperwork about shops and businesses” to create a virtual time machine. An “ambitious project to digitize 10 centuries of the Venetian state’s archives,” the Venice Time Machine uses the latest in “deep learning” technology for historical reconstructions that won’t get washed away.

The Venice Time Machine doesn’t only proof against future calamity. It also sets machines to a task no living human has yet to undertake. Most of the huge collection at the State Archives “has never been read by modern historians,” points out the narrator of the Nature video at the top.

This endeavor stands apart from other digital humanities projects, Alison Abbott writes at Nature, “because of its ambitious scale and the new technologies it hopes to use: from state-of-the-art scanners that could even read unopened books, to adaptable algorithms that will turn handwritten documents into digital, searchable text.”

In addition to posterity, the beneficiaries of this effort include historians, economists, and epidemiologists, “eager to access the written records left by tens of thousands of ordinary citizens.” Lorraine Daston, director of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin describes the anticipation scholars feel in particularly vivid terms: “We are in a state of electrified excitement about the possibilities,” she says, “I am practically salivating.” Project head Frédéric Kaplan, a Professor of Digital Humanities at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), compares the archival collection to “’dark matter’—documents that hardly anyone has studied before.”

Using big data and AI to reconstruct the history of Venice in virtual form will not only make the study of that history a far less hermetic affair; it might also “reshape scholars’ understanding of the past,” Abbott points out, by democratizing narratives and enabling “historians to reconstruct the lives of hundreds of thousands of ordinary people—artisans and shopkeepers, envoys and traders.” The Time Machine’s site touts this development as a “social network of the middle ages,” able to “bring back the past as a common resource for the future.” The comparison might be unfortunate in some respects. Social networks, like cable networks, and like most historical narratives, have become dominated by famous names.

By contrast, the Time Machine model—which could soon lead to AI-created virtual Amsterdam and Paris time machines—promises a more street-level view, and one, moreover, that can engage the public in ways sealed and cloistered artifacts cannot. “We historians were baptized with the dust of archives,” says Daston. “The future may be different.” The future of Venice, in real life, might be uncertain. But thanks to the Venice Time Machine, its past is poised take on thriving new life. See previews of the Time Machine in the videos further up, learn more about the project here, and see Kaplan explain the “information time machine” in his TED talk above.

Related Content:

How Venice Works: 124 Islands, 183 Canals & 438 Bridges

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness