By the late 1970s, New York City had fallen into such a shambolic state that nobody could have been expected to notice the occasional streak of additional spray paint here and there. But somehow the repeated appearance of the word “SAMO” caught the attention of even jaded Lower Manhattanites. That tag signified the work of Al Diaz and Jean-Michel Basquiat, the latter of whom would create work that, four decades later, would sell for over $110 million at auction, a record-breaking number for an American artist. But by then he had already been dead for nearly 20 years, brought down by a heroin overdose at 27, an age that reflects not just his rock-star status in life but his increasingly legendary profile after it.

“Born in 1960 to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat spent his childhood making art and mischief in Boerum Hill,” Brooklyn, says University of Maryland art history professor Jordana Moore Saggese in the animated Ted-Ed introduction above. “While he never attended art school, he learned by wandering through New York galleries, and listening to the music his father played at home.”

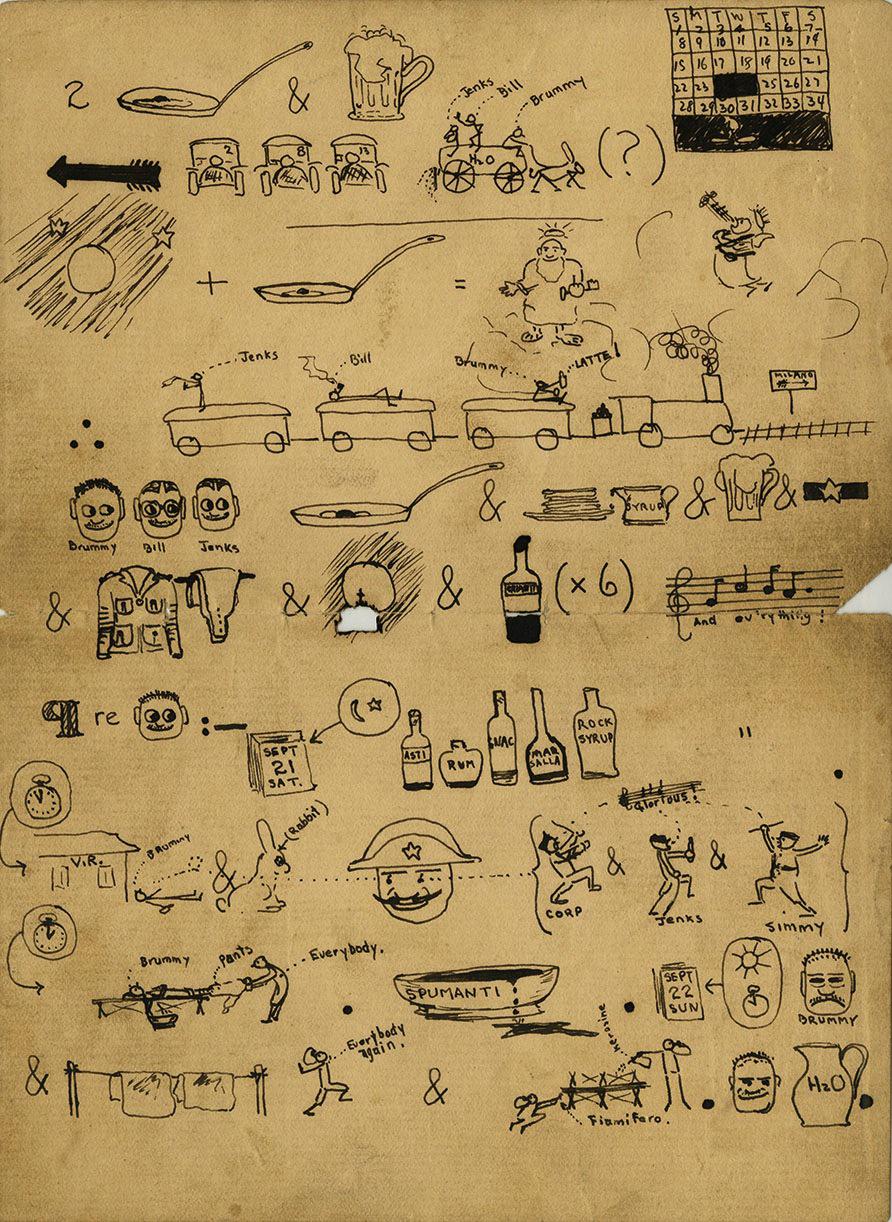

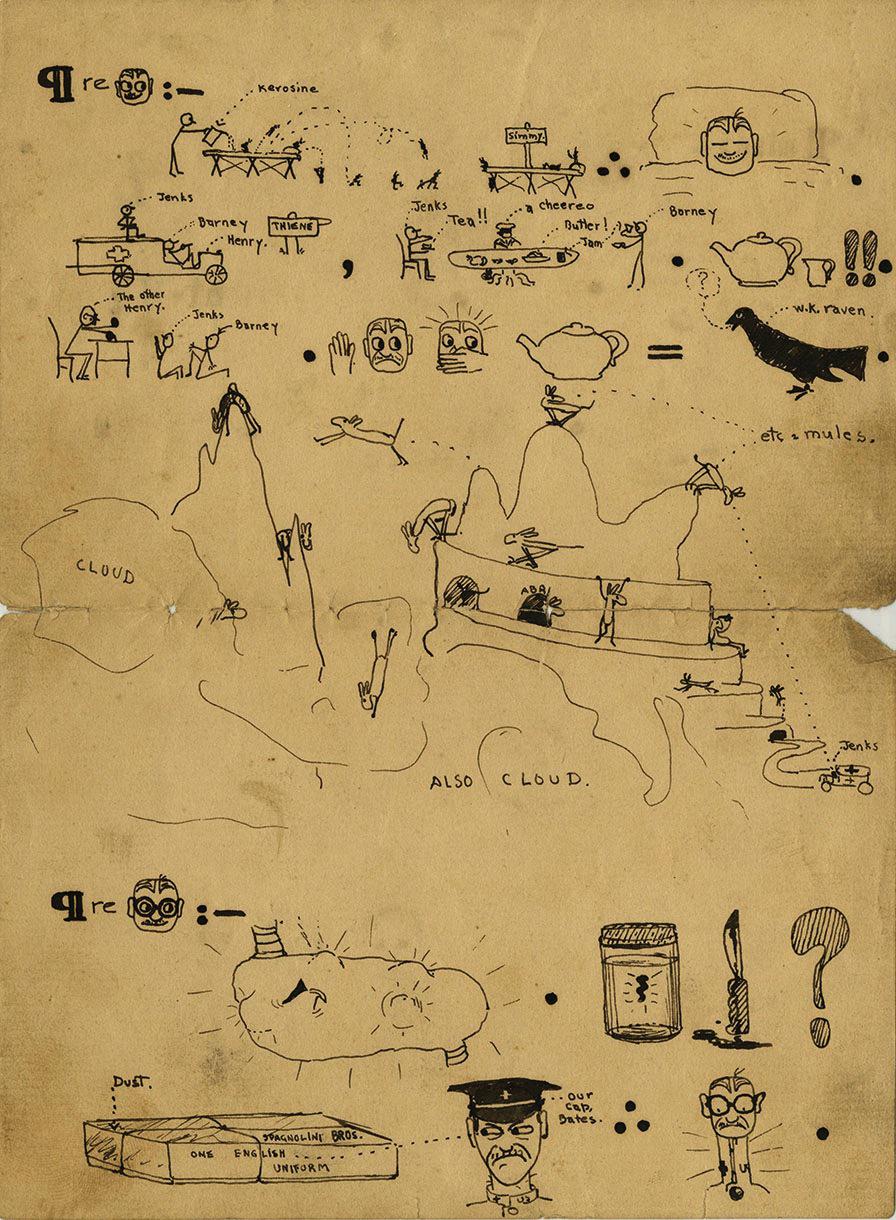

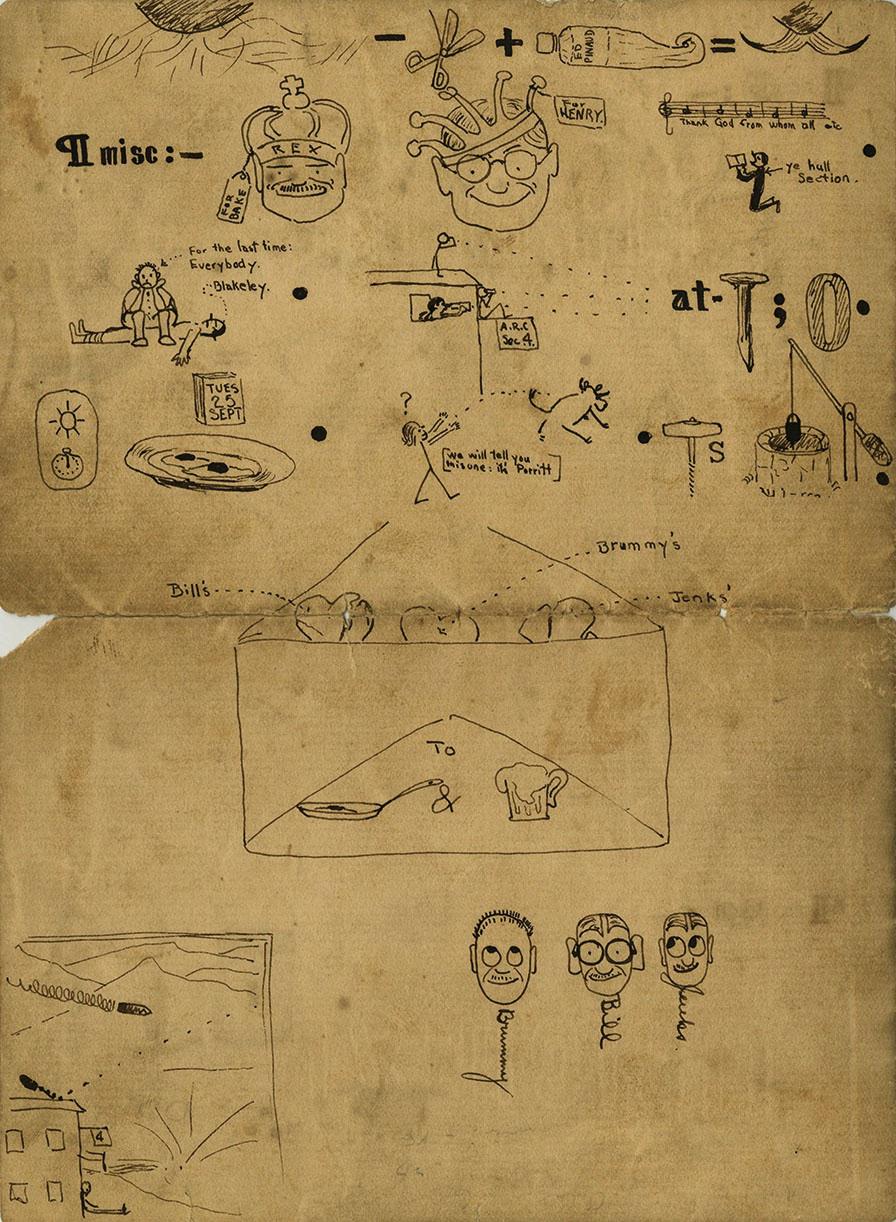

He seems to have drawn inspiration from everything around him, “scribbling his own versions of cartoons, comic books and biblical scenes on scrap paper from his father’s office” (leading to a method that has something in common with William Burroughs’ cut-up techniques). He also spent a great deal of artistically formative time laid up in the hospital after a car accident, poring over a copy of Gray’s Anatomy given to him by his mother, which “ignited a lifelong fascination with anatomy that manifested in the skulls, sinew and guts of his later work.”

A skull happens to feature prominently in that $110 million painting of Basquiat’s, but he also made literally thousands of other works in his short life, having turned full-time to art after SAMO hit it big on the Soho art scene. The day job he quit was at a clothing warehouse, a position he landed, after a period of unemployment and even homelessness, when the company’s founder spotted him spray-painting a building at night. Success came quickly to the young Basquiat, but it certainly didn’t come without effort: still, when we regard his paintings today, don’t we feel compelled by not just what Saggesse calls a distinctive “inventive visual language” and hyper-referential “physical evidence of Basquiat’s restless and prolific mind,” but also of the glimpse they offer into the rare life lived at maximum productivity, maximum intensity, and maximum speed?

To delve deeper into the world of Basquiat, you can watch two documentaries online: Basquiat: Rage to Riches, and Jean Michel Basquiat-The Radiant Child.

Related Content:

The Odd Couple: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 1986

Google Puts Online 10,000 Works of Street Art from Across the Globe

Big Bang Big Boom: Graffiti Stop-Motion Animation Creatively Depicts the Evolution of Life

How to Jumpstart Your Creative Process with William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.