“Though hardly a cinematic masterpiece,” film critic Andre Soares writes, “or even a good film,” Al Jolson’s 1927 The Jazz Singer will forever bear the distinction of “the first time in a feature film that synchronized sound and voices could be heard in musical numbers and talking segments.” What usually goes unremarked in film history is that Indian cinema was never far behind its U.S. counterpart. The country’s first feature sound film appeared just four years after The Jazz Singer. Now lost, the love story Alam Ara debuted in March of 1931 and initiated a venerable tradition with its several songs, including the first major filmi music hit.

The movie was so popular, one historian notes, “police aid had to be summoned to control the crowds.” Its director Ardeshir Irani was inspired by another early Hollywood part-talkie musical, 1929’s Show Boat, which, like his film, used the Movietone system to record sound, rather than the Vitaphone system used in The Jazz Singer. Movietone, or Fox Movietone, as it came to be known after William Fox bought the patents in 1926, was also responsible for another early film development, the sound newsreel, a technology that made its way to India almost as soon as it debuted in the U.S.

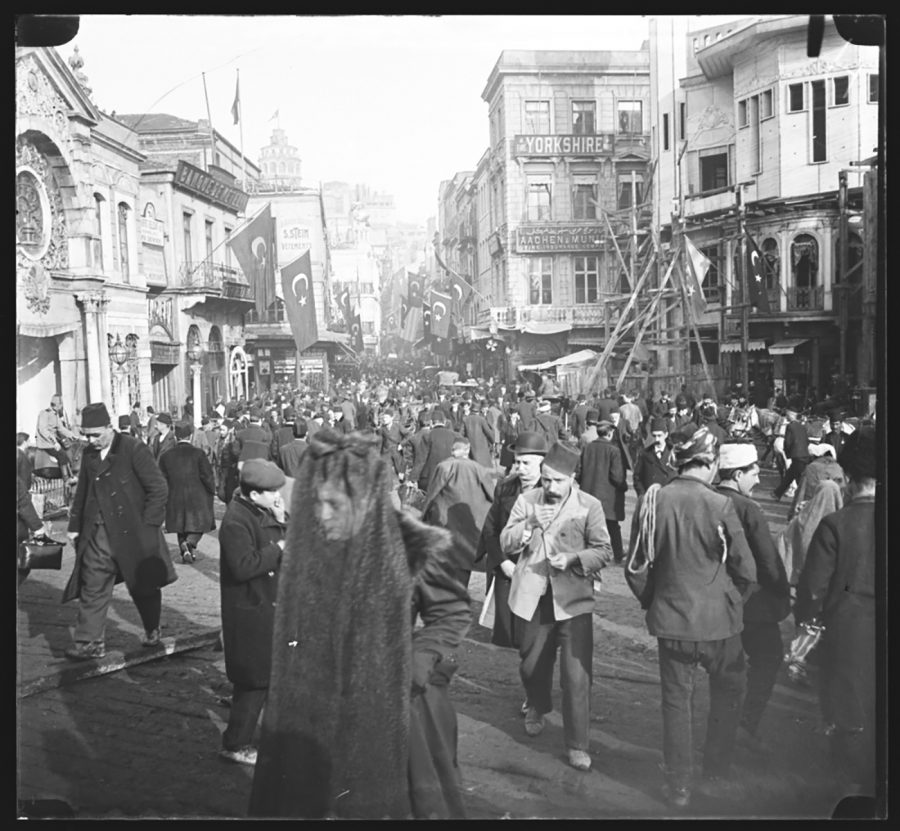

The first sound newsreel, showing footage of Charles Lindbergh’s taking off in the “Spirit of St. Louis,” debuted in 1927 in New York. In November 1929, Fox opened the first exclusive newsreel theater on Broadway, and in January of that same year, a Movietone camera captured the street scenes of Bombay (now Mumbai) that you see above, over 13 minutes of footage complete with live audio recording of bustling crowds, busy vendors and laundry workers, honking automobiles, and clip-clopping horses.

This incredible document preserves the sights and sounds of a significant Indian slice of life from 90 years ago, and shows how early the technology for making sound films arrived on the subcontinent. When Ardeshir Irani began filming his groundbreaking musical the following year, he would use exactly this same technology, shooting all of the dialogue and music live, on a closed set late at night to avoid unwanted noise like the street sounds you hear above.

Learn more of the Fox Movietone newsreel story here, and here, learn how Indian cinema began in Mumbai in 1899 when Indian photographers, writers, theater impresarios, and entrepreneurs like Irani took the new technology and used it to build a cultural empire of their own.

Related Content:

India on Film, 1899–1947: An Archive of 90 Historic Films Now Online

Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911

Download 6600 Free Films from The Prelinger Archives and Use Them However You Like

Free: British Pathé Puts Over 85,000 Historical Films on YouTube

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness