Sometimes I feel

The need to move on

So I pack a bag

And move on

Move on

–David Bowie, “Move On”

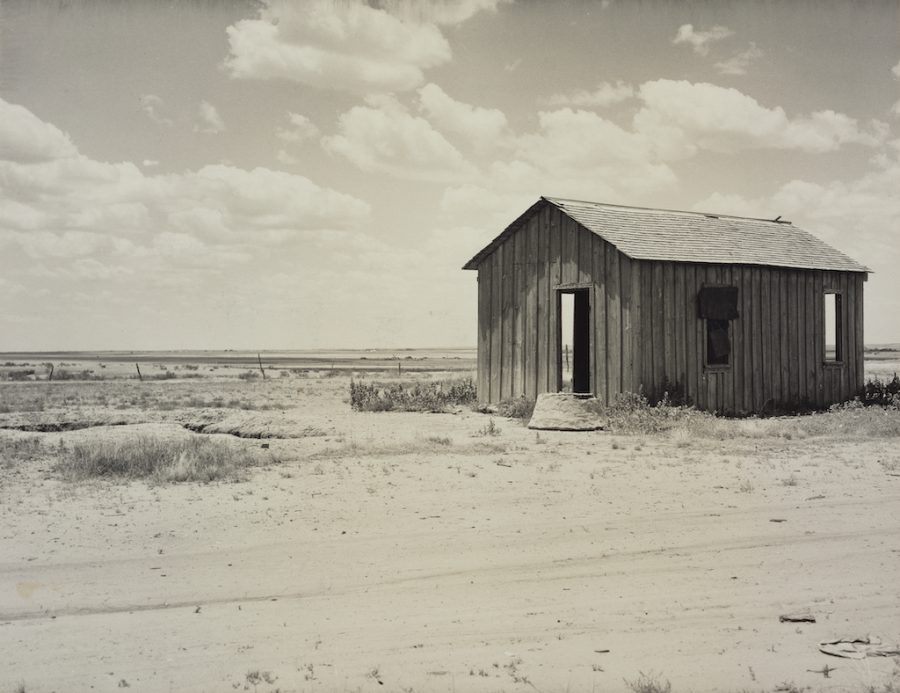

We might have been calling it the Lake Geneva Trilogy, given David Bowie’s recuperative sojourn in Switzerland after the emptiness he felt in L.A. The first album in the Berlin Trilogy, Low, was mostly recorded in France, and the last album of the trilogy, Lodger, in Montreaux in 1979. But they were almost all written in, around, and about Berlin, where Bowie found what he was looking for—a more rarified form of isolation—or as he puts it, “virtual anonymity…. For some reason Berliners just didn’t care. Well, not about an English rock singer, anyway.”

Bowie’s wife Angela remembers that “he chose to live in a section of the city as bleak, anonymous, and culturally lost as possible…. He took an apartment above an auto parts store and ate at the local workingman’s café. Talk about alienation.” The feeling pervades all three albums to different effect, but Lodger takes things in a far edgier, more cacophonous direction. Removed from Bowie’s time of soaking up krautrock and producing his roommate Iggy Pop’s solo albums, recorded as his marriage dissolved, it is the sound of jaded cultural and relational dislocation.

“A lot more chaos was intended” on Lodger says Tony Visconti, and it is on these rocks that composer Philip Glass foundered for 23 years. In the 90s, he began his own trilogy, of symphonies based on the renowned Bowie/Eno/Visconti collaborations. Lodger hung him up because it “didn’t interest me at all,” he tells the Los Angeles Times. Despite its wild experimentalism, he heard “no original ideas on that record.”

Glass gravitated towards the melodies of the first two albums, releasing his Low symphony in 1993 and the equally inspired Heroes in ’96. Finally, just this week, he premiered Lodger, with venerable American composer John Adams conducting, in Los Angeles on what would have been Bowie’s birthday, January 8th.

Though Glass never shared his thoughts about Lodger with Bowie, he may not have needed to. Bowie himself felt that “Tony [Visconti] lost heart a little” during the recording “because it never came together as easily as both Low and “Heroes” had. This had a lot to do with my being distracted by personal events in my life,” he says, though “I would still maintain thought that there are a number of really important ideas on Lodger.” It is on the ideas that Glass seized. “The writing was remarkable. It was someone who had created a political language for themselves.”

While Glass’s other Bowie symphonies drew directly from the albums’ music (the Low symphony opens with the cinematic theme from “Subterraneans”), “What I was going to do on Lodger,” says Glass, “had nothing to do with the music that was on the record.” He realized that he had been given “a whole piece by a very accomplished writer and artist who had a vision of the world” in the lyrics. Employing the unique voice of singer Angélique Kidjo, Glass made what he calls “a song symphony” using seven of the “texts” (he left off “Look Back in Anger,” “D.J.” and “Red Money”).

Glass takes these “poems” as he calls them and weaves them into his own musical fabric. He’s “unconcerned,” writes Randal Roberts at the L.A. Times “with what Bowie would have thought of his method,” but he remembers Bowie was most struck in his other symphonies by “the parts that didn’t sound very much like the original.” At the top of the post, hear “Warszawa” from Glass’s Low symphony and listen to his other Bowie-inspired pieces on Spotify. The Lodger symphony will make its European premier at the Southbank Centre in London in May of this year, and we should hope to see a recording released soon.

Related Content:

The “David Bowie Is” Exhibition Is Now Available as an Augmented Reality Mobile App That’s Narrated by Gary Oldman: For David Bowie’s Birthday Today

Stream David Bowie’s Complete Discography in a 19-Hour Playlist: From His Very First Recordings to His Last

David Bowie’s Top 100 Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness