“The nones are growing,” we hear all the time, a reference to the huge increase in people who check the “none” box in documents that ask about religious beliefs. In the U.S., at least, the response to this news seems to be fivefold: fear, denial, anger, celebration, and speculation that can seem to go beyond what the data warrants. National Geographic, for example, trumpets “The World’s Newest Major Religion: No Religion,” though it’s not exactly clear what no religion means.

Checking “none” does not signify holding specific convictions or affiliations. It can be an irritated reaction from those who find the question intrusive, an evasion from those who refuse to think about the issue, a response from those whose beliefs are not reflected in any of the choices offered, a confident statement of thoroughgoing philosophical naturalism…. One way to look at the data is that it’s inconclusive.

But it could tell some big stories as well, such as “the secularizing West and the rapidly growing rest” (a story complicated by China, the country with the largest “atheist/agnostic” population). While the internet has made it easier for atheists and agnostics to connect and organize, these labels do not name any consistent set of beliefs or non-beliefs, and they can apply to secular humanists as well as to certain adherents of forms of Buddhism, Taoism, paganism, etc., who may not explicitly identify as religious but who have some spiritual practices…

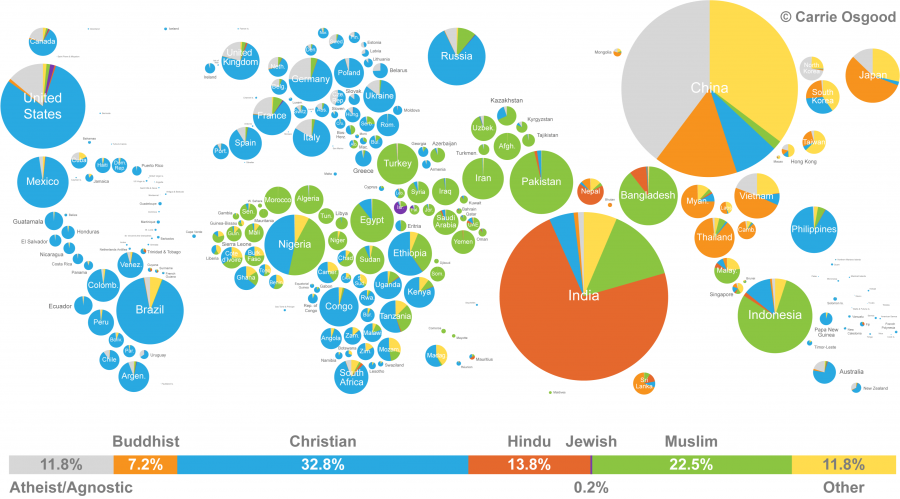

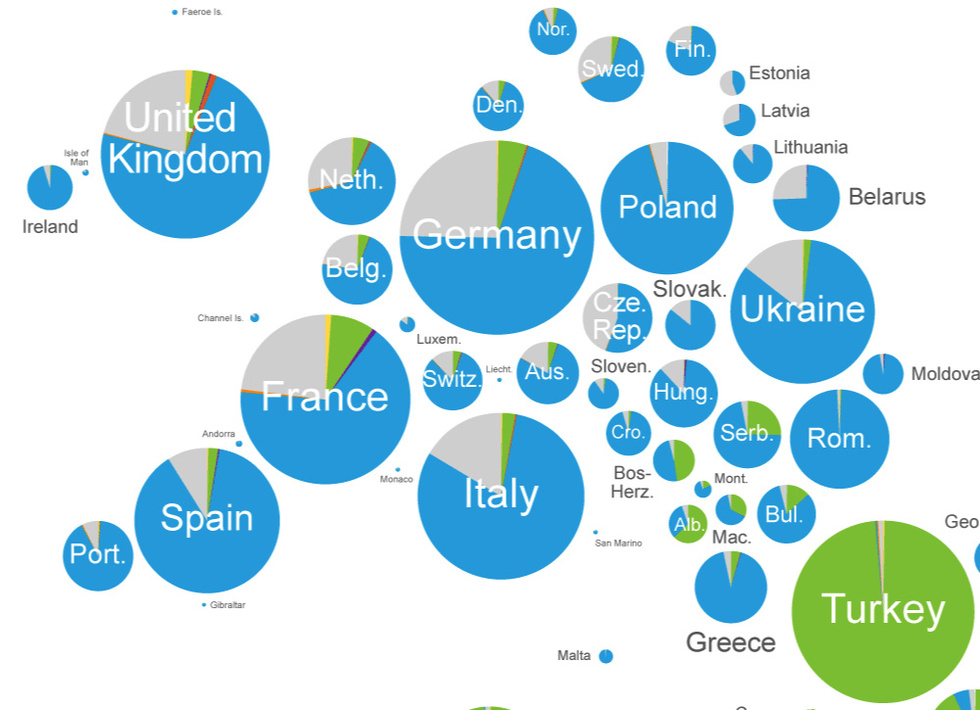

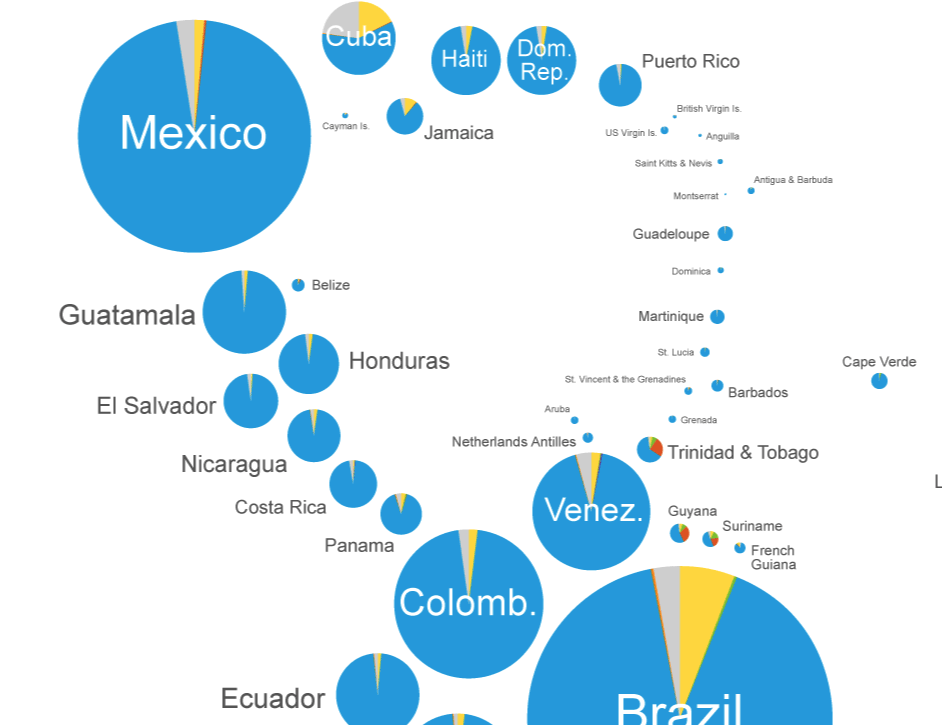

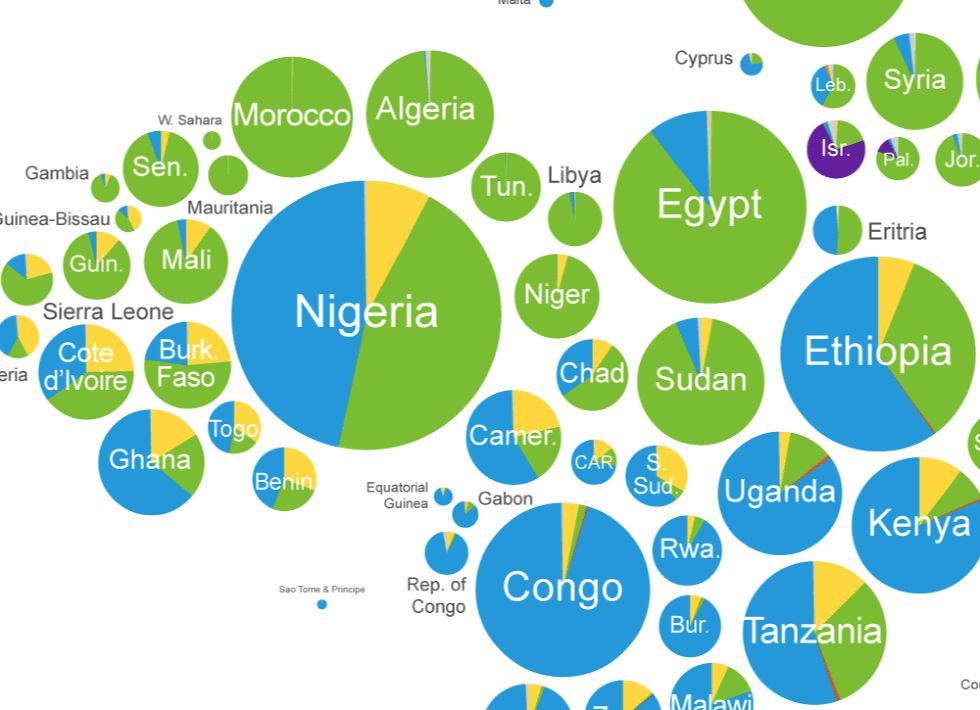

But whoever they are, the “nones” do appear to be growing, accounting for around a quarter of the population in the U.S. and Europe—where in some countries, such as the Czech Republic, closer to half the population identifies as nonreligious. The story of the nones is counterbalanced by the massive spread of religion, mostly Christianity but also Islam, among the “rest” of the world. Designer Carrie Osgood of the world travel site Carrie On Adventures has given us a handy visual reference (view in a large format here) for the global situation in the infographic above.

Drawing on data from the United Nations Population Fund—which she previously used to create a series of population and urbanization maps—and from the World Religion Database, Osgood visualizes the relative populations of each country by sizing them as proportional pie charts, with their major religions represented by different colors. (These numbers are based on 2010 figures and may have changed considerably in the past decade.) Christianity is still the world’s largest religion, at 32.8%, with Islam close behind at 22.5%.

Yet as Frank Jacobs points out at Big Think, such sweeping generalizations—like those about the “nones”—miss critical details needed in any discussion about world religions. “The map bands together various Christian and Islamic schools of thought,” writes Jacobs, “that don’t necessarily accept each other as ‘true believers,’” and may even view each other as enemies and heretics. Large, thriving religious groups like Sikhs are lumped in with “others,” a category that can include numerically marginal or disappearing belief systems.

Likewise, “there’s that whole minefield of nuance between those who practice a religion (but may do so out of social coercion rather than personally held belief), and those who believe in something (but don’t participate in the rituals of any particular faith).” Especially in countries with a majority faith—and with painful social or legal penalties for those who don’t subscribe—the question of how many people really identify out of true conviction cannot be ignored.

Which brings us back to the “nones,” a category, however fuzzy, that may be far larger than the numbers show, and could include millions more in majority-faith countries, if those people lived under a secular government, in a pluralistic society, and felt free to speak their minds. The “nones” have maybe always been around. Only now, in much of the world at least, they’re far more visible. But that’s just one possible story among the many we can tell about this data.

View and download a larger version of the infographic map at Osgood’s site and see a detailed breakdown of the data at Big Think.

Related Content:

Animated Map Shows How the Five Major Religions Spread Across the World (3000 BC – 2000 AD)

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Introduction to the Old Testament: A Free Yale Course

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness