A huge treasure trove of songs and interviews recorded by the legendary folklorist Alan Lomax from the 1940s into the 1990s have been digitized and made available online for free listening. The Association for Cultural Equity, a nonprofit organization founded by Lomax in the 1980s, has posted some 17,000 recordings.

“For the first time,” Cultural Equity Executive Director Don Fleming told NPR’s Joel Rose, “everything that we’ve digitized of Alan’s field recording trips are online, on our Web site. It’s every take, all the way through. False takes, interviews, music.”

It’s an amazing resource. For a quick taste, here are a few examples from one of the best-known areas of Lomax’s research, his recordings of traditional African American culture:

- “John Henry” sung by prisoners at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, Parchman Farm, in 1947.

- “Come Up Horsey,” a children’s lullaby sung in 1948 by Vera Hall, whose mother was a slave.

- “In a Shanty in Old Shanty Town” performed by Big Bill Broonzy, 1952.

- “Story of a slave who asked the devil to take his master,” told by Bessie Jones in 1961.

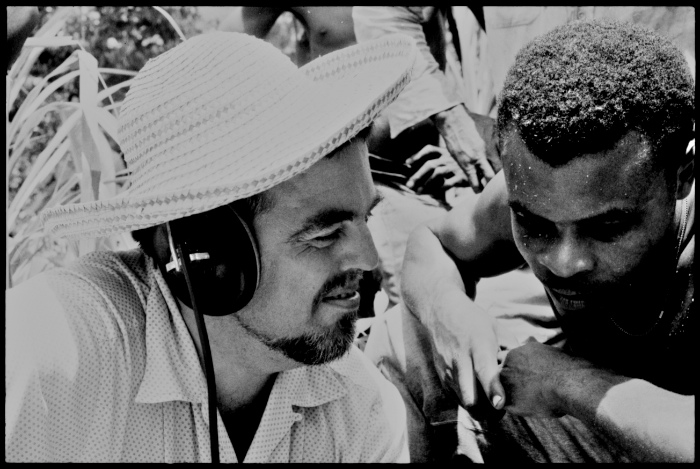

But that’s just scratching the surface of what’s inside the enormous archive. Lomax’s work extended far beyond the Deep South, into other areas and cultures of America, the Caribbean, Europe and Asia. “He believed that all cultures should be looked at on an even playing field,” his daughter Anna Lomax Wood told NPR. “Not that they’re all alike. But they should be given the same dignity, or they had the same dignity and worth as any other.”

You can listen to Rose’s piece about the archive on the NPR website, as well as a 1990 interview with Lomax by Terry Gross of Fresh Air, which includes sample recordings from Woody Guthrie, Jelly Roll Morton, Lead Belly and Mississippi Fred McDowell. To dive into the Lomax audio archive, you can search the vast collection by artist, date, genre, country and other categories.

Note: An earlier version of this post originally appeared on our site in March 2012.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content: