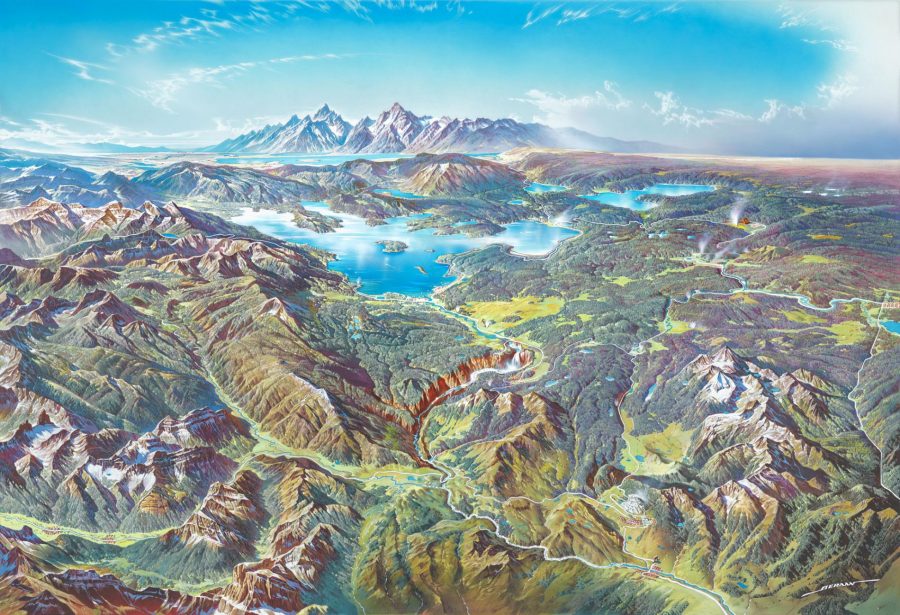

The United States of America’s national parks have been inspiring artists even before they were officially declared national parks. That goes not just for American artists such as the master landscape photographer Ansel Adams, but foreign artists as well. Take the Austrian painter Heinrich C. Berann, described by his official web site as “the father of the modern panorama map,” a distinctive form that allowed him to hybridize “old European painting tradition with modern cartography.”

Berann found his way to cartography after winning a competition to paint a map of Austria’s Grossglockner High Alpine Road, which opened in 1934, a couple years after Berann’s graduation from art school. “In the following years,” says the artist’s bio, “he improved this technique, created the modern panorama map and became famous all over the world for his maps that are in a class of their own.” Maps in a class of their own need geographical subjects in a class of their own, and America’s national parks fit that bill neatly.

Berann’s panoramas of Denali, North Cascades, Yellowstone, and Yosemite “were created in the 1980s and 90s as part of a poster program to promote the national parks,” writes National Geographic’s Betsy Mason. Just a few years ago, U.S. National Park Service senior cartographer Tom Patterson got to work on scanning the artworks in high resolution. When the project was complete, “the National Park Service released the new images on their newly redesigned online map portal, which also has more than a thousand maps that are freely available for the public to download.”

Berann’s 1994 painting of Denali National Park just above was his final work before retirement. It came at the end of a long and varied career in art that saw him paint not just the Alps, the Himalayas, the Virgin Islands, and the floor of the Pacific Ocean (as well as other impressive parts of the world under commission from the National Geographic society and six different Olympic Games) but travel posters and drawings of everything from landscapes to portraits to nudes.

But it is Berann’s panoramic paintings of America’s national parks, which you can download in high resolution here, that have done the most to make people see their subjects in a new way. Not least because, with an artistic sleight-of-hand that combines as many landmarks as possible into single vistas rendered with a strikingly wide range of colors, Berann provides them a series of vantage points entirely unavailable in real life. In one sense, these are all real national parks, but they’re national parks captured in a way even Ansel Adams never could have done.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Browse & Download 1,198 Free High Resolution Maps of U.S. National Parks

Download Iconic National Park Fonts: They’re Now Digitized & Free to Use

Yosemite National Park in All of Its Time-Lapse Splendor

Artist Re-Envisions National Parks in the Style of Tolkien’s Middle Earth Maps

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.