What makes the Beatles the best-known rock band in history? None can deny that they composed songs of unsurpassed catchiness, a quality demonstrated as soon as those songs hit the airwaves. But the past 55 or so years have shown us that they also possess an enduring power to inspire: how many beginning musicians, fired up by their enjoyment of the Beatles, play their first notes each day? The tributes to the music of the Beatles keep coming in non-musical forms as well: take, for example, these Beatles songs turned into vintage book covers and magazine pages by screenwriter and self-described “graphic-arts prankster” Todd Alcott.

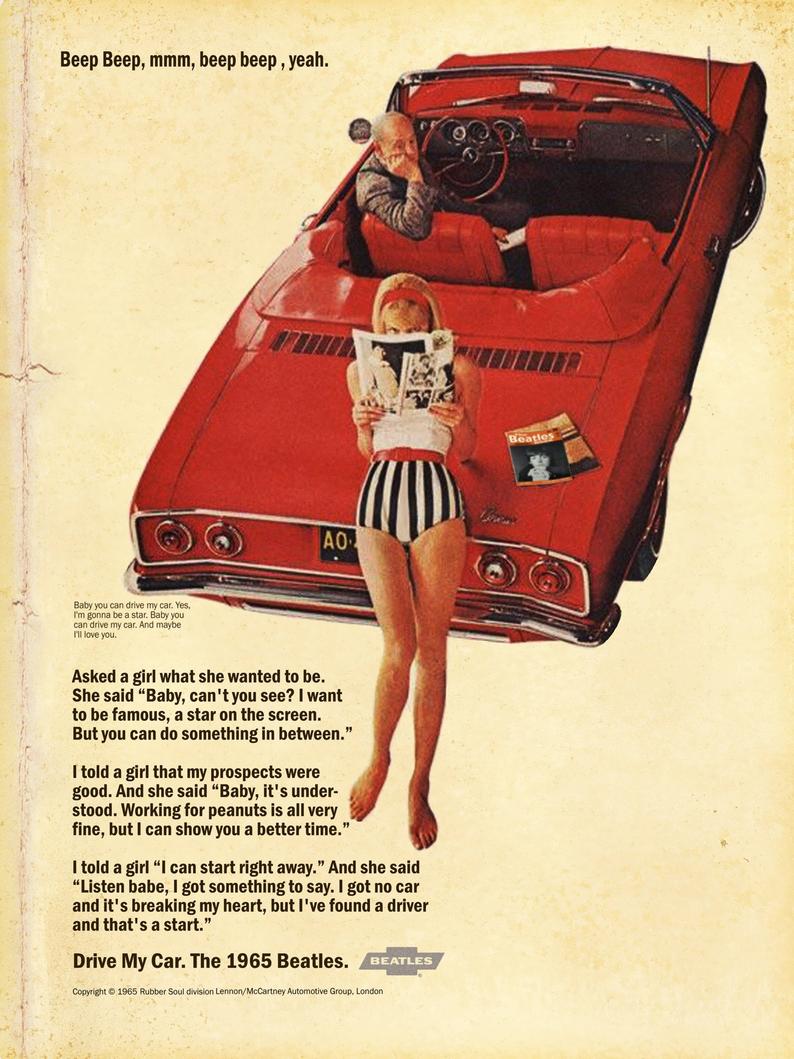

“ ‘Drive My Car’ re-imagines the classic 1965 Beatles song as a classic 1965 advertisement for an actual car,” Alcott writes of the work at the top of the post, “mashing up the image from an ad for a 1966 Chevrolet Corvair with the lyrics from the song.”

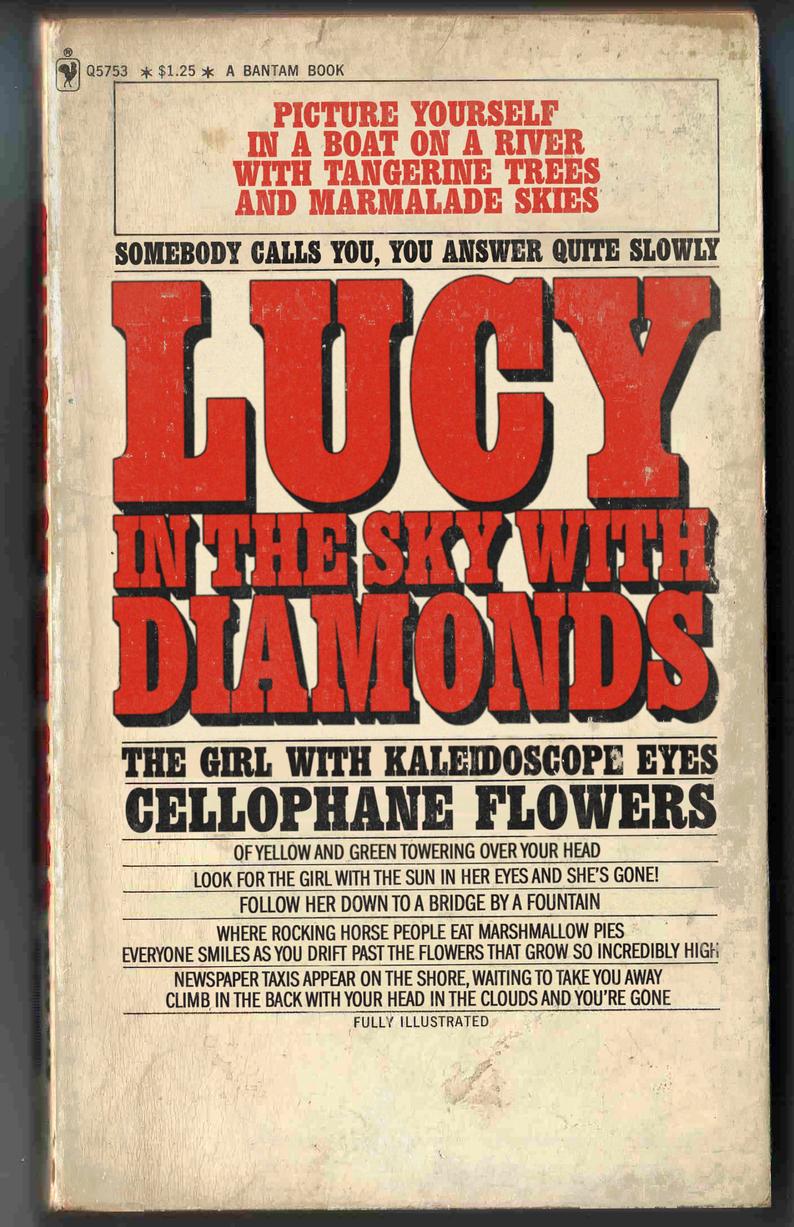

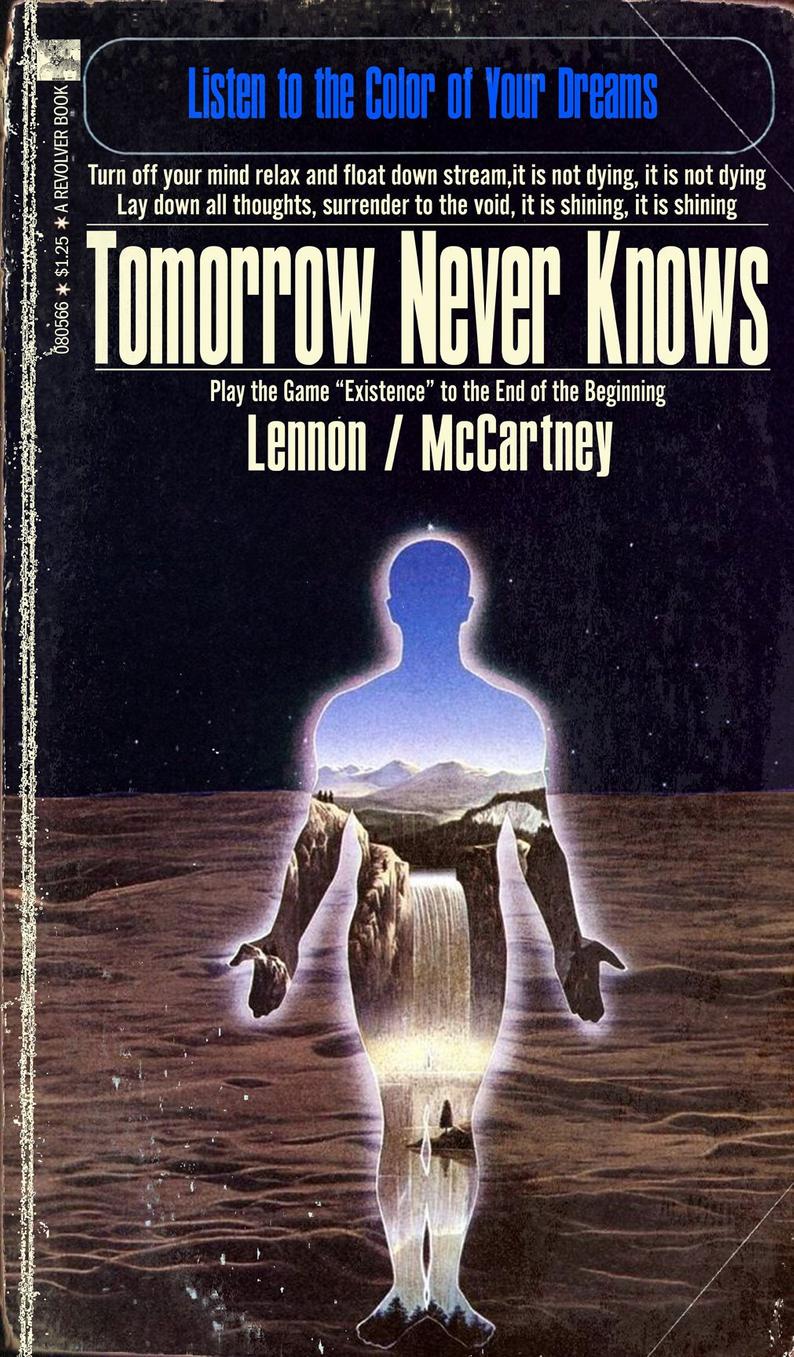

Below that, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” makes of that number a mass-market book cover “in the style of Erich von Daniken’s classic 1970s alien-visitation book Chariots of the Gods?” Below, Alcott’s interpretation of “Tomorrow Never Knows” perfectly re-creates the look (and, with that visible cover wear, the feel) of a heady 1960s science-fiction novel.

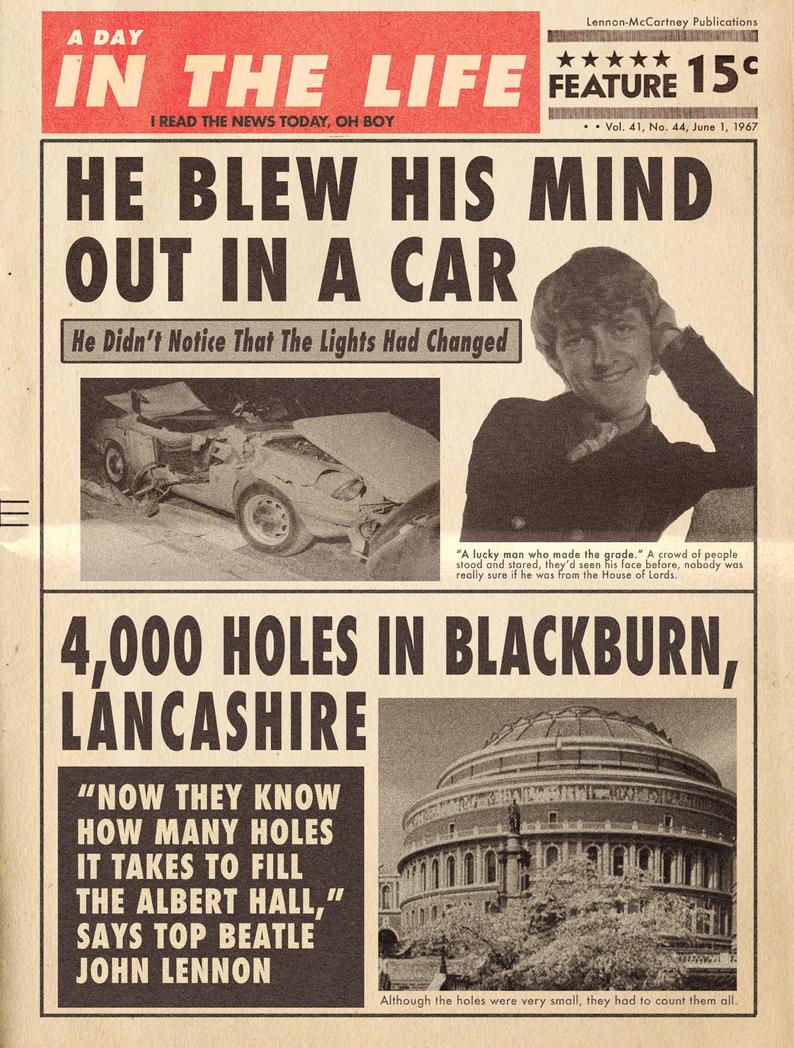

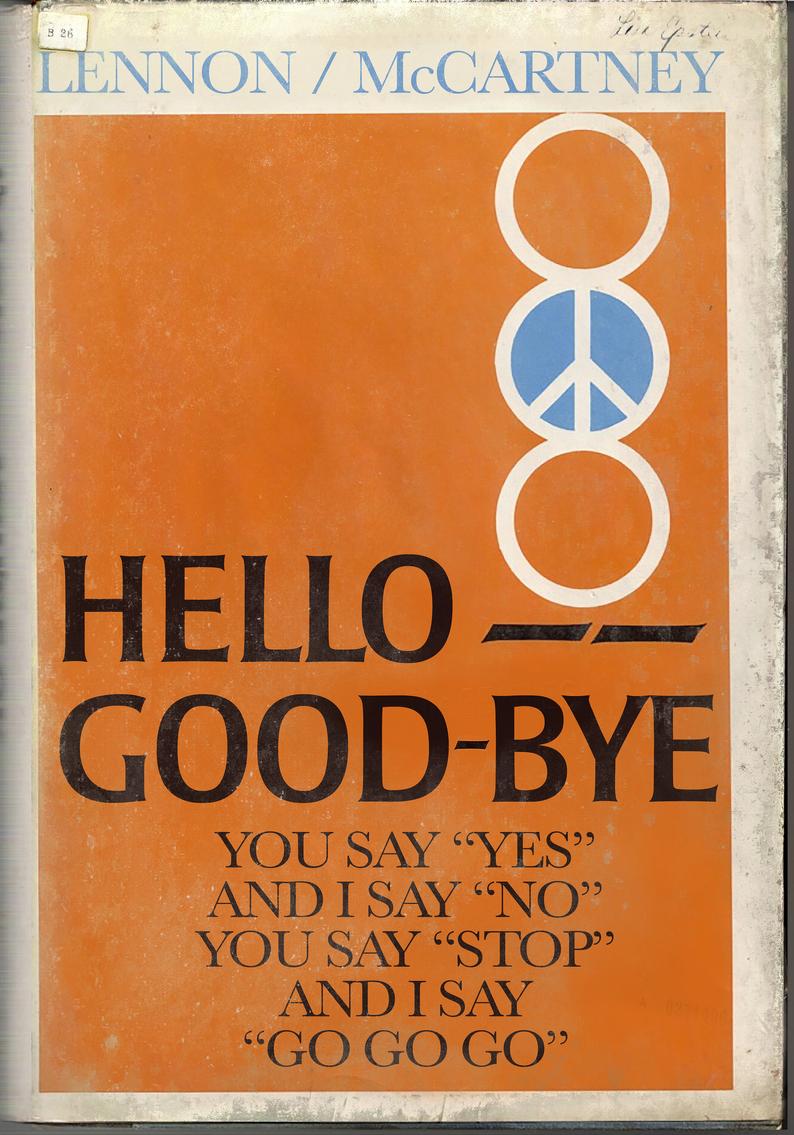

Tomorrow Never Knows does sound like a plausible piece of speculative fiction from that era, but Alcott has made use of much more than these songs’ titles. Even casual Beatles fans will notice how much of their lyrical content he manages to work into his designs, for which the 1967 National Enquirer cover pastiche he put together for the 1967 single “A Day in the Life” (“complete with photos of Tory Browne, the Guinness heir about whom the song was written”) offered an especially rich opportunity. Just when the Beatles broke up in real life, the era of the new-age self-help book began, and after seeing what Alcott did with “Hello Goodbye” using the distinctive visual branding of that publishing trend, you’ll wonder why no one cashed in on such a combination at the time.

You can see all of Alcott’s Beatles book cover and magazine page designs, and buy prints of them in various sizes, over at Etsy. Other selections include “Rocky Raccoon” as an 1880s dime novel (publishers of which included a firm named Beadles) and “Revolution” as a Soviet history book. Open Culture readers will know Alcott from his previous forays into retro music-to-book graphic design, which took the songs of David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Radiohead and others and re-imagined them as sci-fi novels, pulp-fiction magazines, and other artifacts of print culture from times past. In the case of the Beatles, Alcott’s formidable skill at evoking a highly specific era of recent history with an image underscores, by contrast, the timelessness of the songs that inspired them.

Related Content:

A Short Film on the Famous Crosswalk From the Beatles’ Abbey Road Album Cover

How The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Changed Album Cover Design Forever

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.