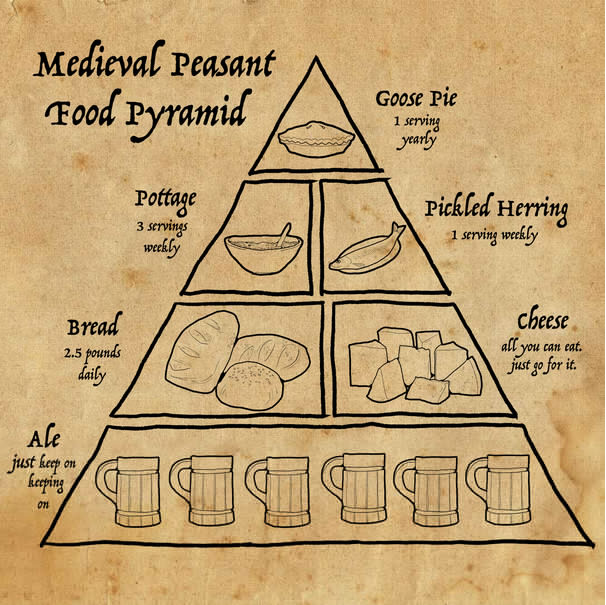

In 2005, the U.S. Department of Agriculture revised its famous food pyramid, jettisoning the familiar hierarchical graphic in favor of vertical rainbow stripes representing the various nutritional groups. A stick figure bounded up a staircase built into one side, to reinforce the idea of adding regular physical activity to all those whole grains and veggies.

The dietary information it promoted was an improvement on the original, but nutritional scientists were skeptical that the public would be able to parse the confusing graphic, and by and large this proved to be the case.

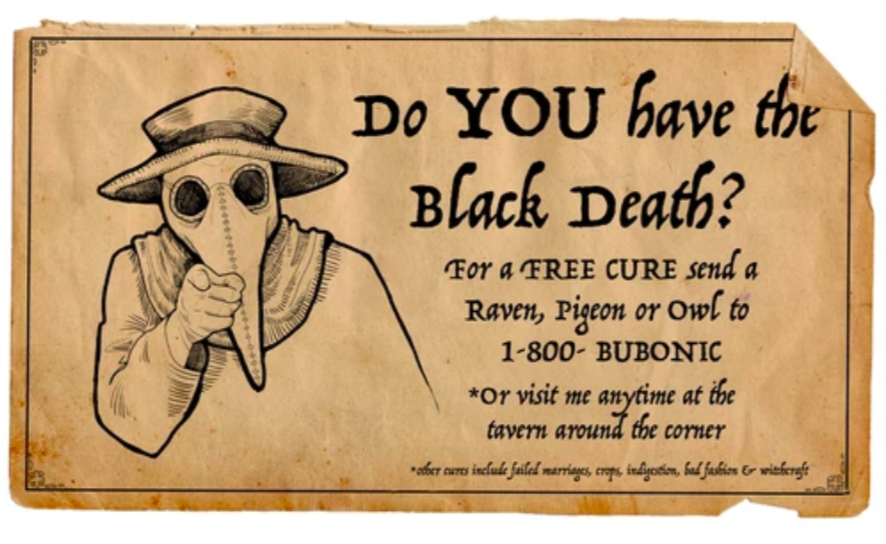

Artist Tyler Gunther, however, was inspired:

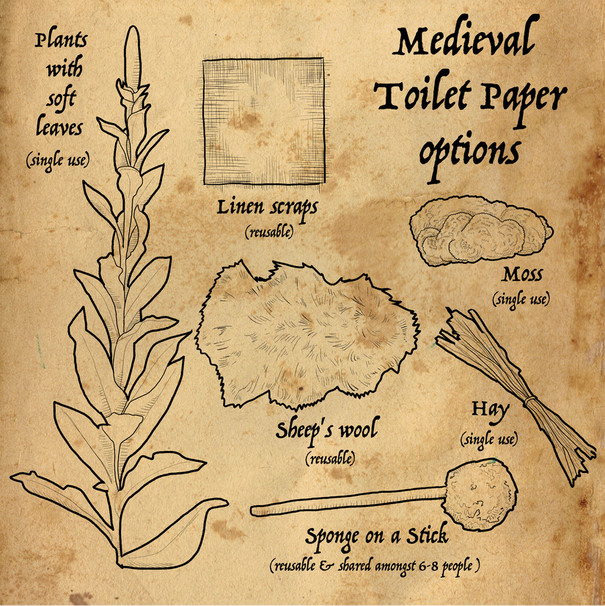

I started thinking about the messaging school children in 1308 were force fed to believe was part of a heart healthy diet, only to have the rug pulled out from under them 15 years later when some monk rearranged the whole thing.

In other words, you’d better dig into that annual goose pie, kids, while you’ve still got 6 glasses of ale to wash it down.

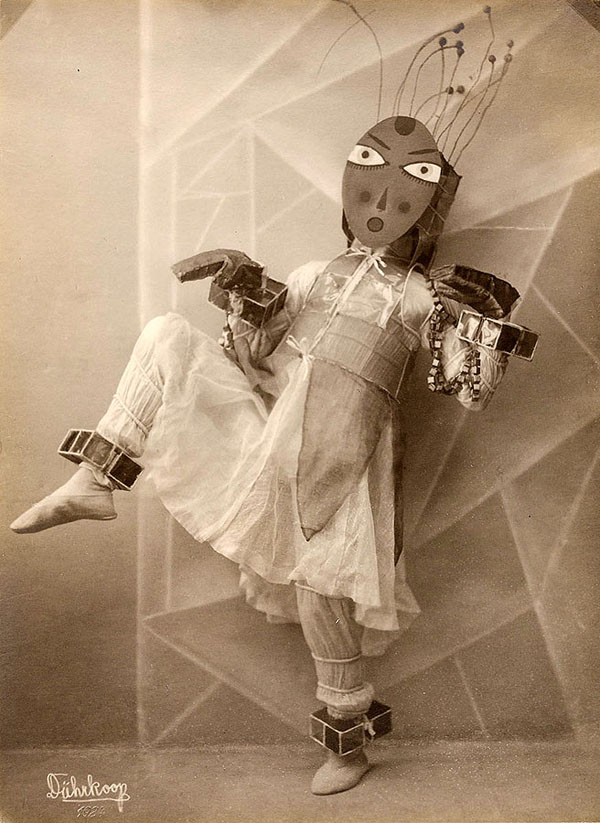

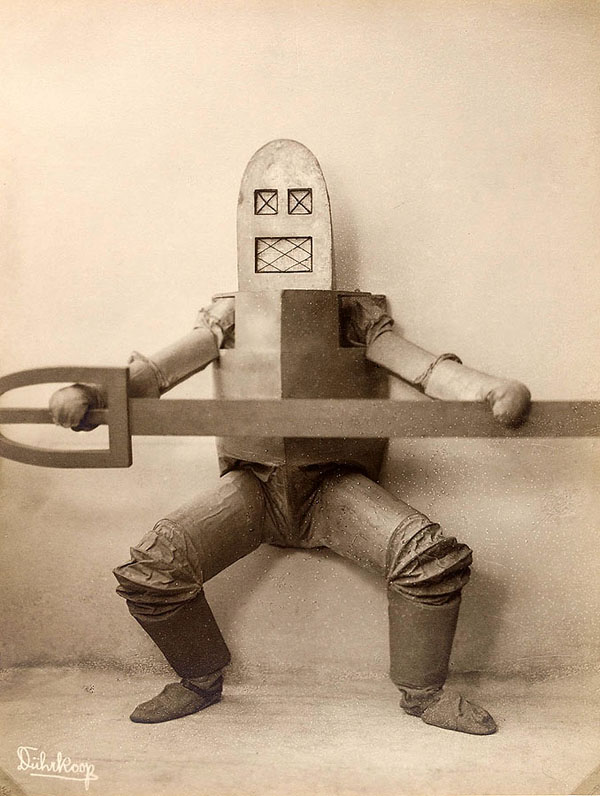

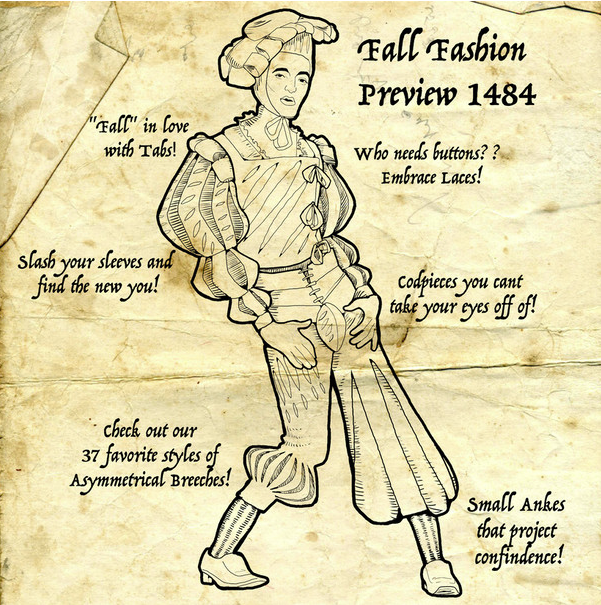

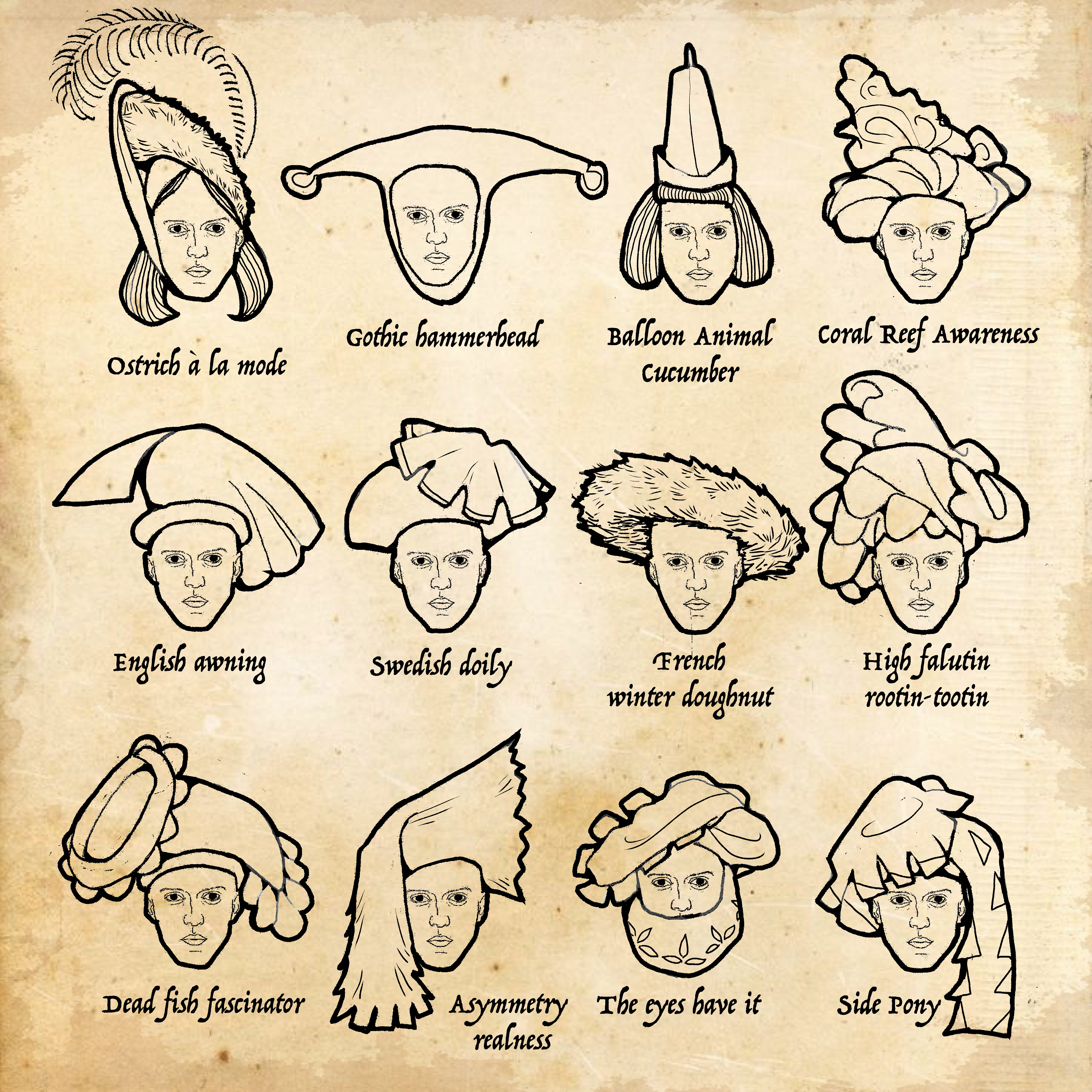

The imagined overlap between the modern and the medieval is a fertile vein for Gunter, whose MFA in Costume Design is often put to good use in his hilarious historical comics:

Modern men’s fashion is so incredibly boring. A guy wears a pattered shirt with a suit and he gets lauded as though he won the super bowl of fashion. But back in the Middle Ages men made bold, brave fashion choices and I admire them greatly for this. It’s so exciting to me to think of these inventive, strange, fantastic creations being a part of the everyday masculine aesthetic.

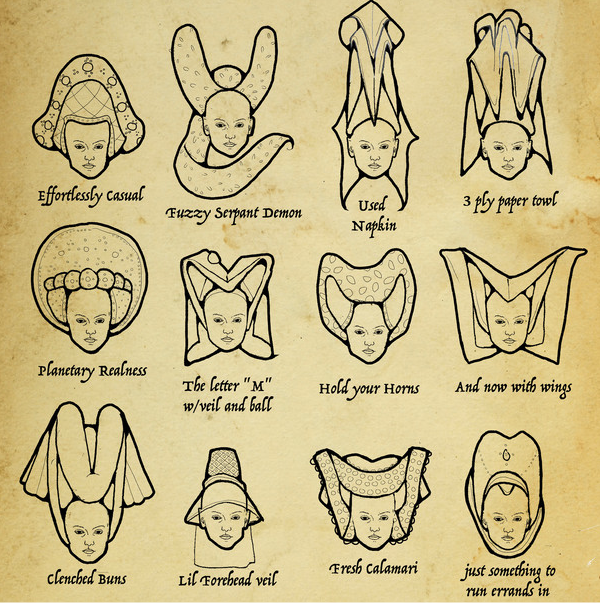

The shapes and structures of women’s headwear in the dark ages are truly inspiring. Where were these milliners drawing inspiration from? How were they engineered? How comfortable were they to wear? How did they fit through the majority of doorways? What was it like to sit behind a particularly large one in church? I’m still scrolling through many an internet history blog to find the answers.

Kathryn Warner’s Edward II blog has proved a helpful resource, as has Anne H. van Buren’s book Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands.

The Brooklyn-based, Arkansas-born artist also makes periodic pilgrimages to the Cloisters, where the Metropolitan Museum houses a vast number illuminated manuscripts, panel paintings, altar pieces, and the famed Unicorn Tapestries:

On my first trip to The Cloisters I saw a painting of St. Michael and the devil almost immediately. I don’t think my life or art has been the same since. None of us know what the devil looks like. But you wouldn’t know that based on how confidently this artist portrays his likeness. After gazing at this painting for an extended period of time I wanted so badly to understand the imagination of whoever could imagine an alligator arms/face crotch/dragon ponytail combo. I don’t think I’ve come close to scratching the surface.

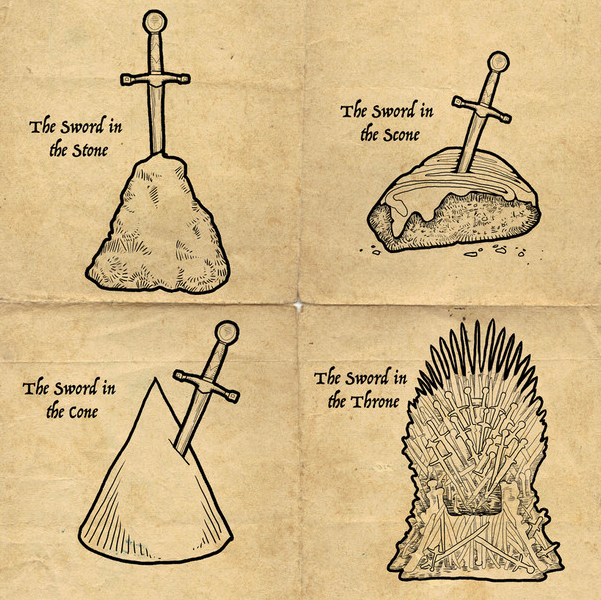

Every time I go to that museum I think, “Wow it’s like I’m on Game of Thrones” and then I have to remind myself kindly that this was real life. Almost everything there was an object that people interacted with as part of their average daily life and that fascinates me as someone who lives in a world filled with mass produced, plastic objects.

Gunther’s drawings and comics are created (and aged) on that most modern of conveniences—the iPad.

The British monarchy and the First Ladies are also sources of fascination, but the middle ages are his primary passion, to the point where he recently costumed himself as a page to tell the story of Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall and Edward II’s darling, aided by a garment rack he’d retooled as a medieval pageant cart-cum-puppet theater.

See the rest of Tyler Gunther’s Medieval Comics on his website and don’t forget to surprise your favorite hygienist or oral surgeon with his Medieval Dentist print this holiday season.

All images used with permission of artist Tyler Gunther

Related Content:

How to Make a Medieval Manuscript: An Introduction in 7 Videos

Medieval Monks Complained About Constant Distractions: Learn How They Worked to Overcome Them

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley, with a special appearance by Tyler Gunther. Follow her @AyunHalliday.