The history of Hollywood film before 1968 breaks down into two eras: “pre-Code” and “post-Code.” The “Code” in question is the Motion Picture Production Code, better known as the “Hays Code,” a reference to Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America president Will H. Hays. The organization we now know as the MPAA hired Hays in 1922, tasking the Presbyterian deacon and former chairman of the Republican National Committee and Postmaster General with “cleaning up” early Hollywood’s sinful image. Eight years into Hays’ presidency came the Code, a pre-emptive act of self-censorship meant to dictate the morally acceptable — and more importantly, the morally unacceptable — content in American film.

“The code sets up high standards of performance for motion-picture producers,” NPR’s Bob Mondello quotes Hays as saying at the Code’s 1930 debut. “It states the considerations which good taste and community value make necessary in this universal form of entertainment.” No picture, for example, should “lower the moral standards of those who see it,” and “the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.” There was also “an updated, much-expanded list of ‘don’ts’ and ‘be carefuls,’ with bans on nudity, suggestive dancing and lustful kissing. The mocking of religion and the depiction of illegal drug use were prohibited, as were interracial romance, revenge plots and the showing of a crime method clearly enough that it might be imitated.”

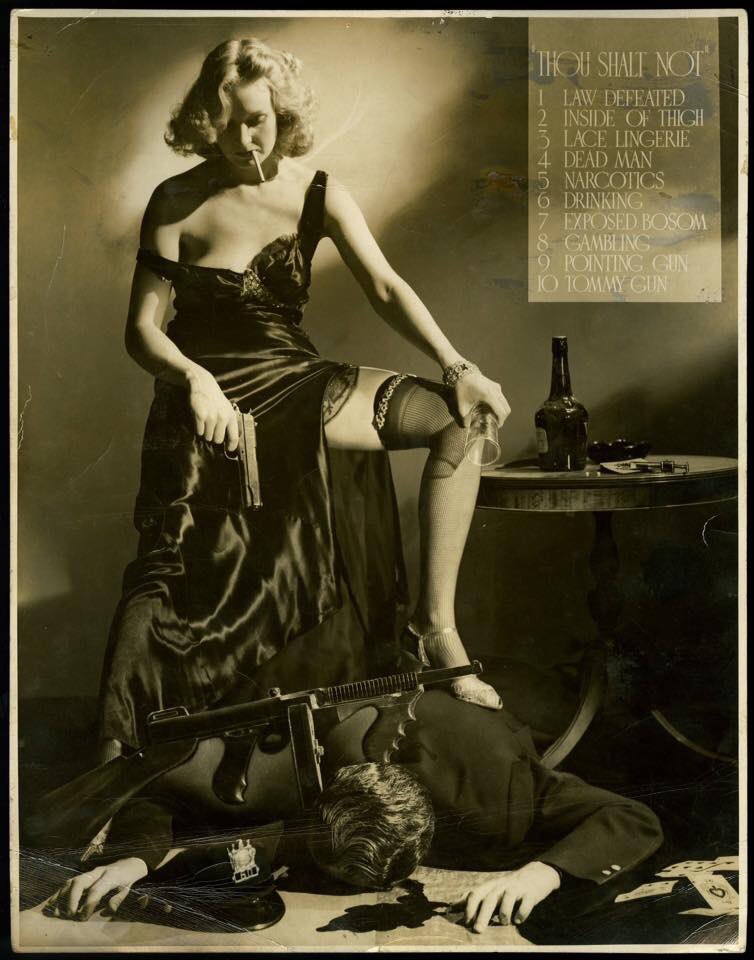

Serious enforcement of the Code commenced in 1934, and it didn’t take long thereafter for Hollywood filmmakers to start flouting it. “American film producers are inured by now to the Hays Office which regulates movie morals,” says a Life article from 1946. Indeed, “knowing that things banned by the code will help sell tickets,” those producers “have been subtly getting around the code for years.” In other words, they “observe its letter and violate its spirit as much as possible.” Atop the article appears an enormous photograph, taken by Paramount photographer A. L. “Whitey” Schafer, that “shows, in one fell swoop, many things producers must not do,” or rather must not depict: the defeat of the law, the inside of the thigh, narcotics, drinking, an “exposed bosom,” a tommy gun, and so on.

For 1941’s inaugural Hollywood Studios’ Still Show, “Schafer decided to create a novelty shot to satirically slap at the Production Code, the censorship standards of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Assn,” writes Hollywood historian Mary Mallory. “His satirical image, entitled, “Thou Shalt Not,” displayed the top 10 faux-pas disallowed by industry censors, who approved every photographic image shot by studios before they could be distributed.” When “outraged organizers pulled the image from the competition” and threatened Schaefer with a fine, he explained that “all the judges were hoarding the 18 prints submitted for the show.” Few of us today would feel so titillated, let alone morally corrupted, by Schafer’s image, but as filmmaker Aislinn Clarke recently demonstrated on Twitter, it may offer more pure entertainment value than ever.

(via @AislinnClarke)

Related Content:

A Brief History of Hollywood Censorship and the Ratings System

The 5 Essential Rules of Film Noir

The Essential Elements of Film Noir Explained in One Grand Infographic

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.