Like many New Yorkers, retired sanitation worker Nelson Molina has a keen interest in his fellow citizens’ discards.

But whereas others risk bedbugs for the occasional curbside score or dumpster dive as an enviro-political act, Molina’s interest is couched in the curatorial.

The bulk of his collection was amassed between 1981 and 2015, while he was on active duty in Carnegie Hill and East Harlem, collecting garbage in an area bordered by 96th Street, Fifth Avenue, 106th Street, and First Avenue.

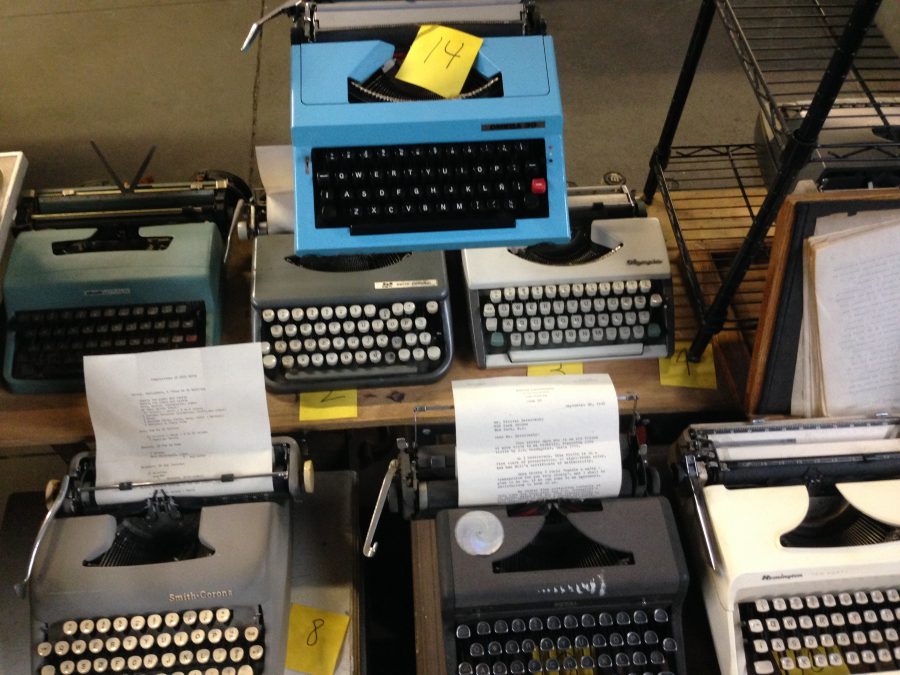

At the end of every shift, he stashed the day’s finds at the garage. With the support of his coworkers and higher ups, his hobby crept beyond the confines of his personal area, filling the locker room, and eventually expanding across the massive second floor of Manhattan East Sanitation Garage Number 11, at which point it was declared an unofficial museum with the unconventional name of Treasures in the Trash.

Because the museum is situated inside a working garage, visitors can only access the collection during infrequent, specially arranged tours. Hunter College’s East Harlem gallery and the City Reliquary have hosted traveling exhibits.

The Foundation for New York’s Strongest (a nickname originally conferred on the Department of Sanitation’s football team) is raising funds for an offsite museum to showcase Molina’s 45,000+ treasures, along with exhibits dedicated to “DSNY’s rich history.”

Molina’s former coworkers marvel at his unerring instinct for knowing when an undistinguished-looking bag of refuse contains an object worth saving, from autographed baseballs and books to keepsakes of a deeply personal nature, like photo albums, engraved watches, and wedding samplers.

There’s also a fair amount of seemingly disposable junk—obsolete consumer technology, fast food toys, and “collectibles” that in retrospect were mere fad. Molina displays them en masse, their sheer numbers becoming a source of wonder. That’s a lot of Pez dispensers, Tamagotchis, and plastic Furbees that could be cluttering up a landfill (or Ebay).

Some of the items Molina singles out for show and tell in Nicolas Heller’s documentary short, at the top, seem like they could have considerable resell value. One man’s trash, you know…

But city sanitation workers are prohibited from taking their finds home, which may explain why Department of Sanitation employees (and Molina’s wife) have embraced the museum so enthusiastically.

Even though Molina retired after raising his six kids, he continues to preside over the museum, reviewing treasures that other sanitation workers have salvaged for his approval, and deciding which merit inclusion in the collection.

Preservation is in his blood, having been raised to repair rather than discard, a practice he used to put into play at Christmas, when he would present his siblings with toys he’d rescued and resurrected.

This thrifty ethos accounts for a large part of the pleasure he takes in his collection.

As to why or how his more sentimental or historically significant artifacts wound up bagged for curbside pickup, he leaves the speculation to visitors of a more narrative bent.

Sign up for updates or make a donation to the Foundation for New York’s Strongest’s campaign to rehouse the collection in an open-to-the-public space here.

To inquire about the possibility of upcoming tours, email the NYC Department of Sanitation at to***@ds**.gov.

Photos of Treasures in the Trash by Ayun Halliday, © 2018

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Although she lives and works inside Nelson Molina’s former pick up zone, she has yet to see any of her discards on display. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley. Follow her @AyunHalliday.