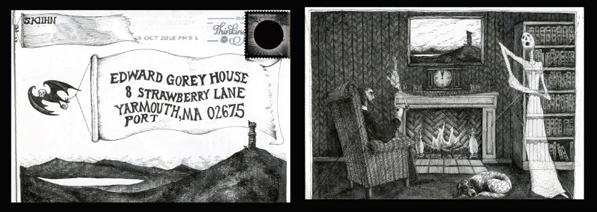

What a delight it must have been to have been one of Edward Gorey’s correspondents, or even a postal worker charged with handling his outgoing mail.

The late author and illustrator had a penchant for embellishing envelopes with the hairy beasts, poker-faced children, and cats who are the mainstays of his darkly humorous aesthetic.

(A number of these envelopes and some 60 postcards and sketches are included in Floating Worlds: The Letters of Edward Gorey and Peter F. Neumeyer, which documents the correspondence-based friendship between Gorey and the author with whom he collaborated on three children’s books, including the delightfully macabre Donald Has a Difficulty.)

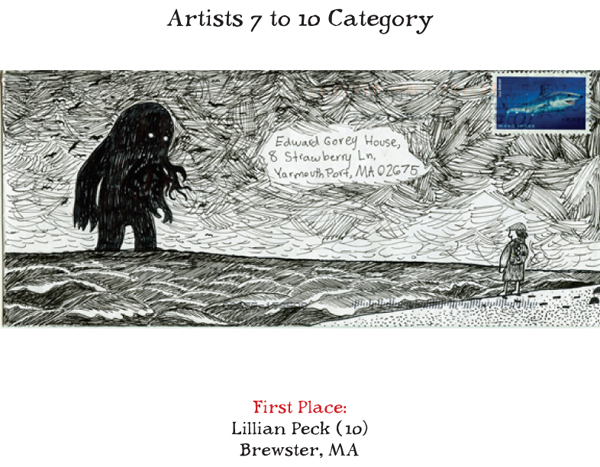

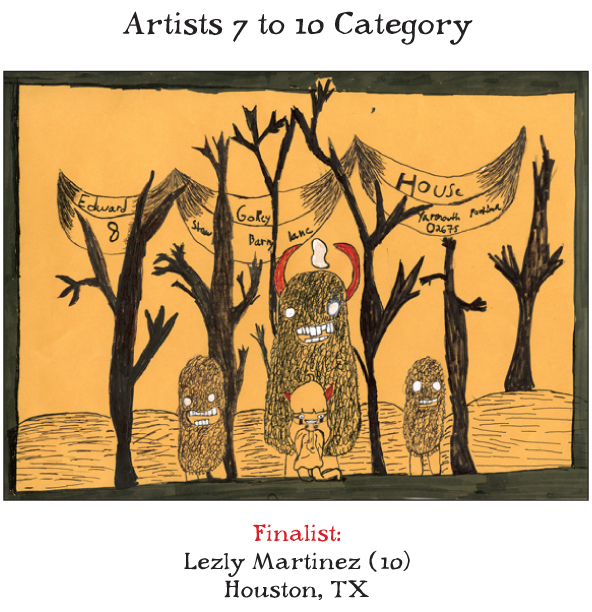

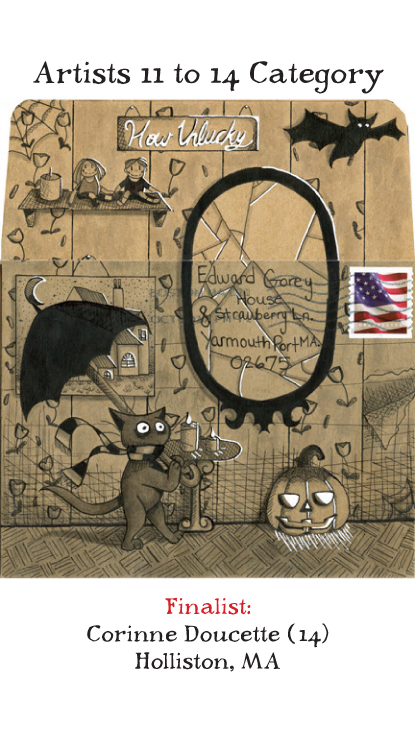

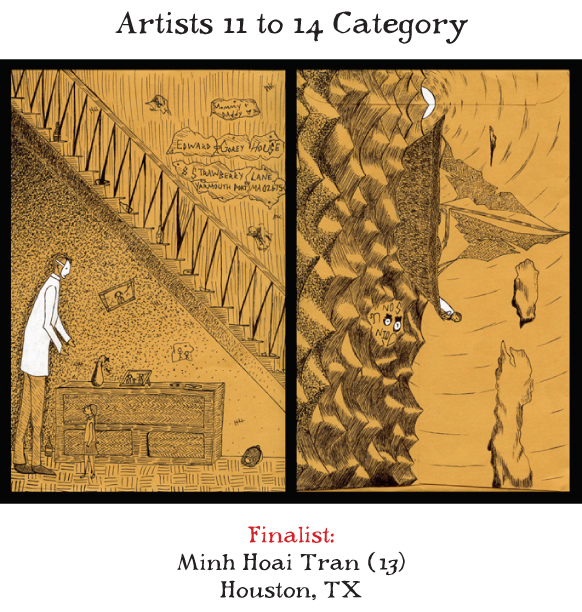

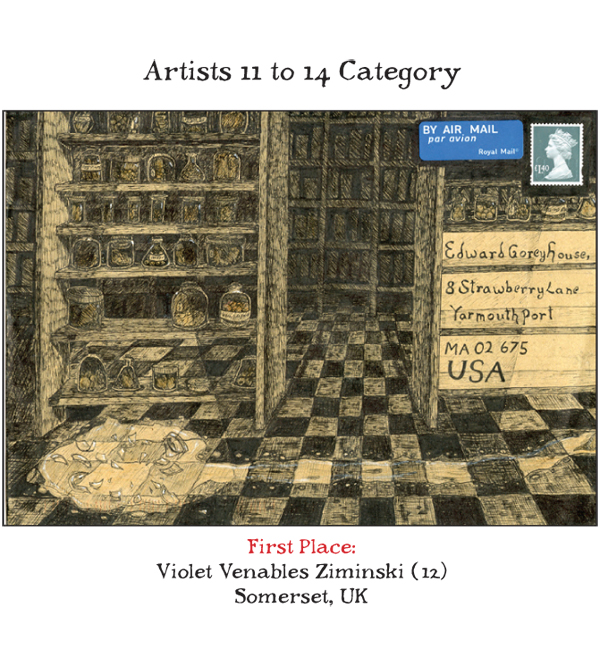

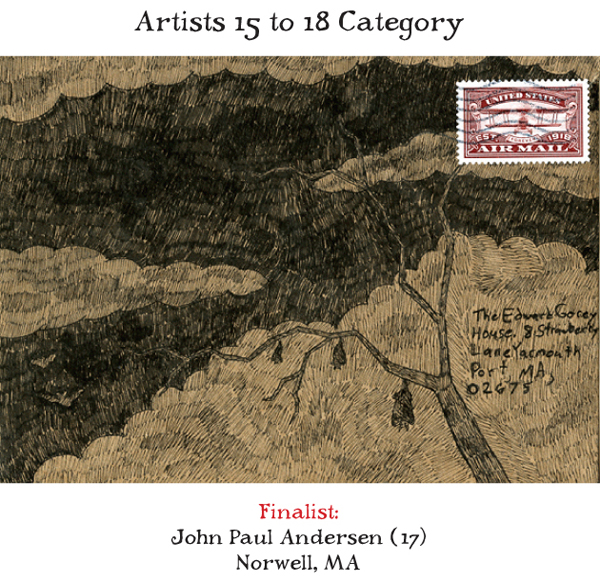

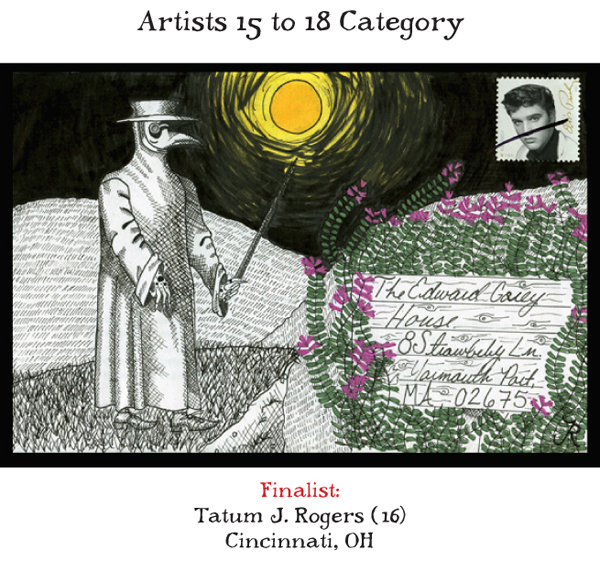

The Edward Gorey House, a beloved Cape Cod residence turned museum, has been keeping the tradition alive with its annual Halloween Envelope Art Contest.

Competitors of all ages vie for the opportunity to have their winning (and runners up and “very-close-to-being-runners-up”) Gorey-inspired entries displayed in the Gorey House and its digital extensions.

2019’s theme is the highly evocative “Uncomfortable Creatures” … and depending on the speed with which you can execute a brilliant idea and deliver it to the post office, you may still have a shot—entries must be postmarked by Monday, October 21, with winners to be announced on Halloween.

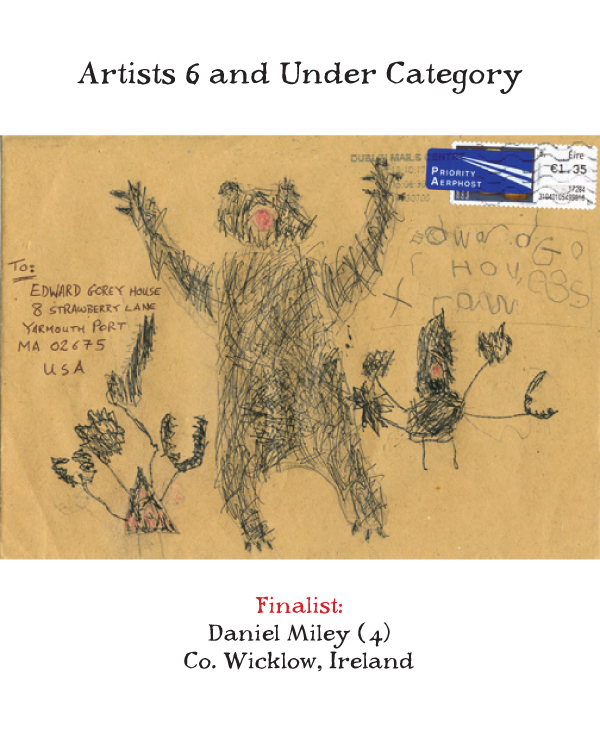

In addition to Stef Kiihn Aschenbrenner’s winning envelope from the 2018 contest’s over-18 category (top), some of our favorites from past years are reproduced here. Our inky-black hearts are especially warmed to see the spirit of the master kindling the imaginations of the youngest entrants—special shout out to Daniel Miley, aged 4.

View five years’ worth of notable Halloween Envelope Contest entries on the Edward Gorey House website (2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014) or download the official entry form and race to the post office with your bid for 2019 glory.

Entries must be postmarked by Monday, October 21 and addressed to Edward Gorey House, 8 Strawberry Lane, Yarmouth Port, MA 02675 USA.

Related Content:

Lemony Snicket Reveals His Edward Gorey Obsession in an Upcoming Animated Documentary

Edward Gorey Talks About His Love Cats & More in the Animated Series, “Goreytelling”

Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, November 4 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates Louise Jordan Miln’s “Wooings and Weddings in Many Climes (1900). Follow her @AyunHalliday.