The American West has never been a place so much as a constellation of events—incursion, settlement, seizure, war, containment, and extermination in one order or another. These bloody histories, sanitized and seen through anti-indigenous ideology, formed the backdrop for the American Western—a genre that depends for its existence on creating a convincing sense of place.

But where most Westerns are supposed to be set—Colorado, California, Texas, Kansas, or Montana—seems less important than that their scenery conform to a stereotype of what The West should look like. That image has, in film after film, been supplied by the towering buttes of Monument Valley. The Vox video above tells the story of how this particular place became the symbol of the American West, beginning with the ironic fact that Monument Valley isn’t actually part of the U.S., but a tribal park on the Navajo Nation reservation, inside the states of Utah and Arizona.

“For centuries, only Native Americans, specifically the Paiute and Navajo, occupied this remote landscape, fielding conflicts with the U.S. government.” That would change when settlers and sheep traders Harry and Leone “Mike” Goulding set up a trading post right outside Navajo territory on the Utah side. Goulding tried tirelessly to attract tourists to Monument Valley during the Great Depression but didn’t get any traction until he took photos of the landscape to Hollywood.

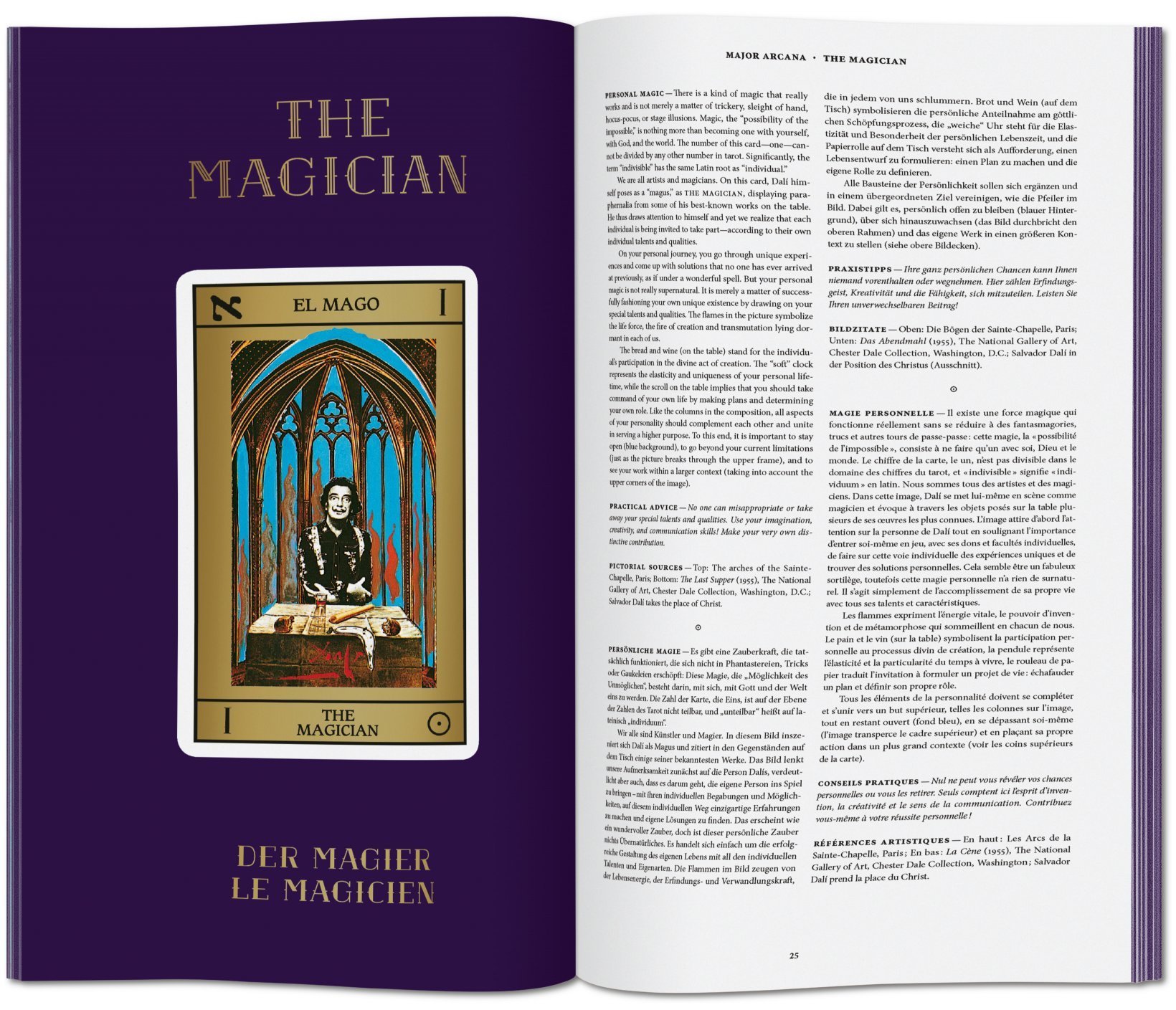

The movie world immediately saw potential, and Western directing legend John Ford chose the stunning location for his 1939 film Stagecoach. It would be the first of scores of films shot in Monument Valley and the origin of cinematic iconography now inseparable from our idea of the rugged American West. The landscape, and Ford’s vision, elevated the Western from low-budget pulp to “one of Hollywood’s most popular genres for the next 20 years.”

Photo by Dsdugan, via Wikimedia Commons

Stagecoach provided the “breakout role for American icon John Wayne” (who once declared that Native people “selfishly tried to keep their land” for themselves and thus deserved to be dispossessed.) And just as Wayne became the face of the Western hero, Monument Valley became the central icon of its mythos. Ford used Monument Valley seven more times in his films, most notably in The Searchers, set in Texas, widely praised as one of the best Westerns ever made.

Ford’s final film to feature the landscape takes place all over the country, appropriately, given its title, How the West Was Won. Its all-star cast, including Wayne, sold this major 1962 epic, marketed with the tagline “24 great stars in the mightiest adventure ever filmed.” But it wouldn’t have been a true Western at that point, or not a true John Ford Western, without Monument Valley as one of its many landscapes. The imagery may have become cliché, but “clichés are useful for storytelling,” signaling to audiences “what kind of story this is.”

From Stagecoach to Marlboro Ads to Thelma and Louise to The Lego Movie to the Cohen Brothers’ comic classic Western tribute The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the image of Monument Valley has become shorthand for freedom, adventure, and the risks of the frontier. But like other iconic places in other forbidding landscapes around the world, the myth of Monument Valley covers over the historical and present-day struggles of real people. We get a little bit of that story in the Vox explainer, but mostly we learn how Monument Valley became an endlessly repeating “backdrop” that “could be anywhere in the West.”

Related Content:

The Great Train Robbery: Where Westerns Began

John Wayne: 26 Free Western Films Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness