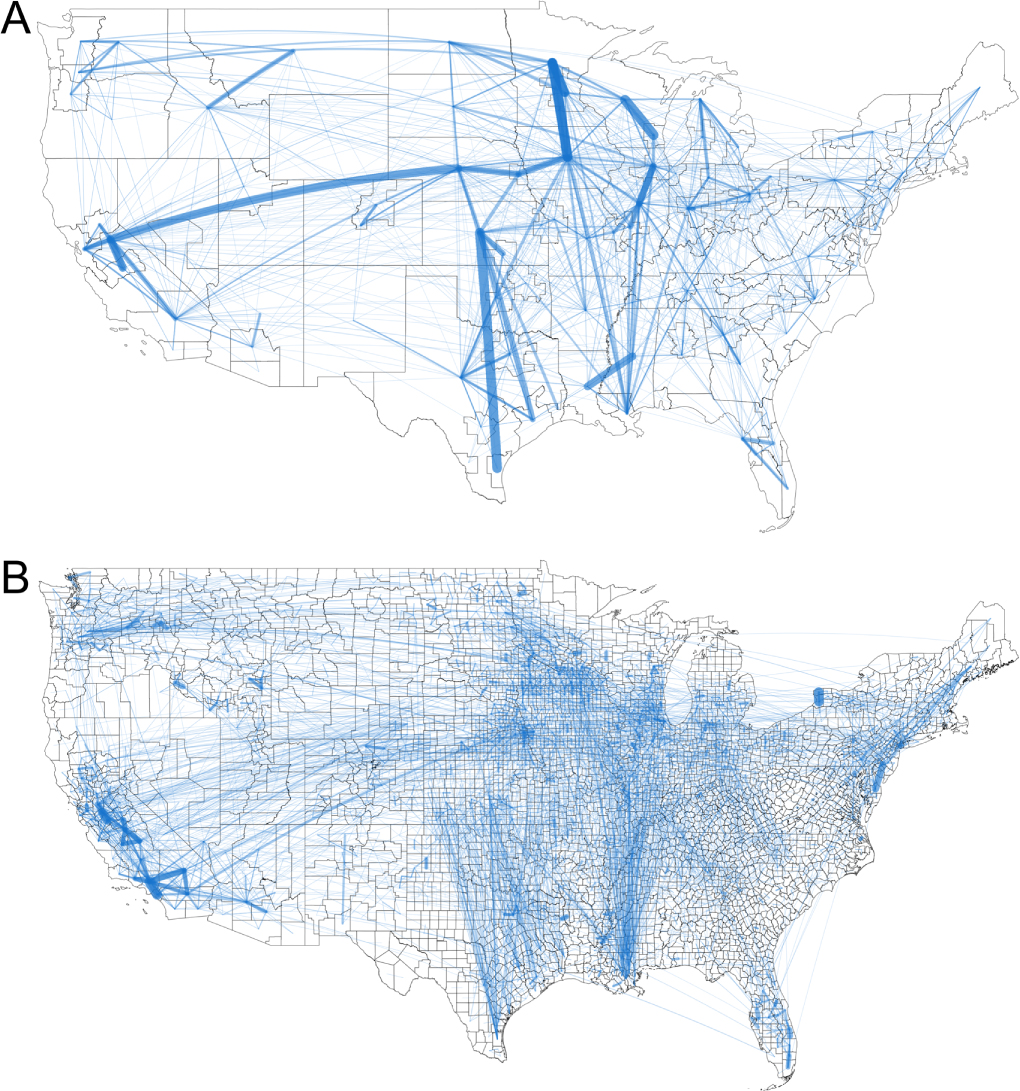

The phrase “farm to table” has enjoyed vogue status in American dining long enough to be facing displacement by an even trendier successor, “farm to fork.” These labels reflect a new awareness — or an aspiration to awareness — of where, exactly, the food Americans eat comes from. A vast and fertile land, the United States produces a great deal of its own food, but given the distance of most of its population centers from most of its agricultural centers, it also has to move nearly as great a deal of food over long domestic distances. Here we have the very first high-resolution map of that food supply chain, created by researchers at the University of Illinois studying “food flows between counties in the United States.”

“Our map is a comprehensive snapshot of all food flows between counties in the U.S. – grains, fruits and vegetables, animal feed, and processed food items,” writes Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Megan Konar in an explanatory post at The Conversation. (The top version shows the total tons of food moved, and the bottom one is broken down to the county scale.)

“All Americans, from urban to rural are connected through the food system. Consumers all rely on distant producers; agricultural processing plants; food storage like grain silos and grocery stores; and food transportation systems.” The map visualizes such journeys as that of a shipment of corn, which “starts at a farm in Illinois, travels to a grain elevator in Iowa before heading to a feedlot in Kansas, and then travels in animal products being sent to grocery stores in Chicago.”

Konar and her collaborators’ research arrives at a few surprising conclusions, such as that Los Angeles county is both the largest shipper and receiver of food in the U.S. Not only that, but almost all of the nine counties “most central to the overall structure of the food supply network” are in California. This may surprise anyone who has laid eyes on the sublimely huge agricultural landscapes of the Midwest “Cornbelt.” But as Konar notes, “Our estimates are for 2012, an extreme drought year in the Cornbelt. So, in another year, the network may look different.” And of the grain produced in the Midwest, much “is transported to the Port of New Orleans for export. This primarily occurs via the waterways of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.”

Konar also warns of troubling frailties: “The infrastructure along these waterways—such as locks 52 and 53—are critical, but have not been overhauled since their construction in 1929,” and if they were to fail, “commodity transport and supply chains would be completely disrupted.” The analytical minds at Hacker News have been discussing the implications of the research shown on this map, including whether the U.S. food supply chain is really, as one commenter put it, “very brittle and contains many weak points.” The American Society of Civil Engineers, as Konar tells Food & Wine, has given the country’s civil engineering infrastructure a grade of D+, which at least implies considerable room for improvement. But against what from some angles look like long odds, food keeps getting from American farms to American tables — and American forks, American mouths, American stomachs, and so on.

Related Content:

Download 91,000 Historic Maps from the Massive David Rumsey Map Collection

View and Download Nearly 60,000 Maps from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.