Given that you’re reading this on the Internet, we presume you’ll be able to define many of the over 800 words that were added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 2018:

biohacking

bougie

bingeable

guac

hangry

Latinx

mocktail

zoodles

But what about some of the humdingers lexicographer Kory Stamper, former associate editor for Merriam-Webster and author of Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries, unleashes in the above video?

prescriptivism

etymological fallicist

(Bonus: bird strike)

And here we thought we were fluent in our native tongue. Face palm, to use another newish entry and an example of descriptivism. (It’s when the dictionary follows the culture’s lead, according novelty its due by officially recognizing words that have entered the parlance, rather than prescribing the way citizens should be speaking.)

To hear Stamper tell it, dictionary writing is a dream gig for readers as well as word lovers.

Part of every day is spent reading, flagging any unfamiliar words that may pop up for further research.

Did teenage slang give rise to it?

Was it born of business trends or tech industry advances?

Stamper is adamant that language is not fixed, but rather a living organism. Words go in and out of fashion, and take on meanings beyond the ones they sported when first included in the dictionary. (Have a look at “extra” to see some evolutionary effects of the English language and back it up with a peek inside the Urban Dictionary.)

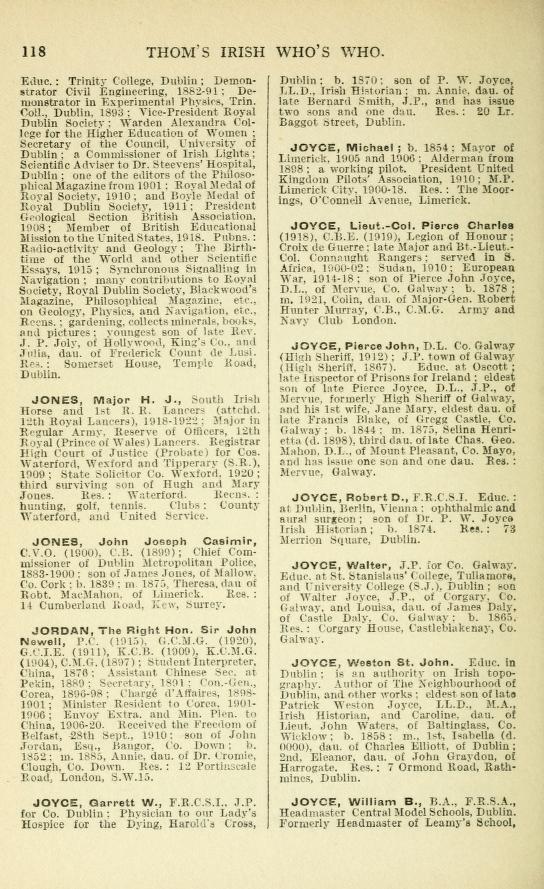

Before a word passes dictionary muster, it must meet three criteria: it must have crossed into widespread use, it seems likely to stick around for a while, and it must have some sort of substantive meaning, as opposed to being known solely for its length (“antidisestablishmentarianism”), or some other structural wonder.

“Iouea” contains all five regular vowels and no other letters. The fact that it exists to describe a genus of sea sponges may seem somewhat beside the point to all but marine biologists.

What new words will enter the lexicon in 2019?

Perhaps we should look to the past. We set Merriam-Webster’s Time Traveler dial back 100 years to discover the words that debuted in 1919. There’s an abundance of goodies here, some of whose WWI-era context has already expanded to accommodate modern meaning (anti-stress, fanboy, superpimp, unbuffered). Readers, care to take a stab at freshening up some other candidates:

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. See her onstage in New York City January 14 as host of Theater of the Apes book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.