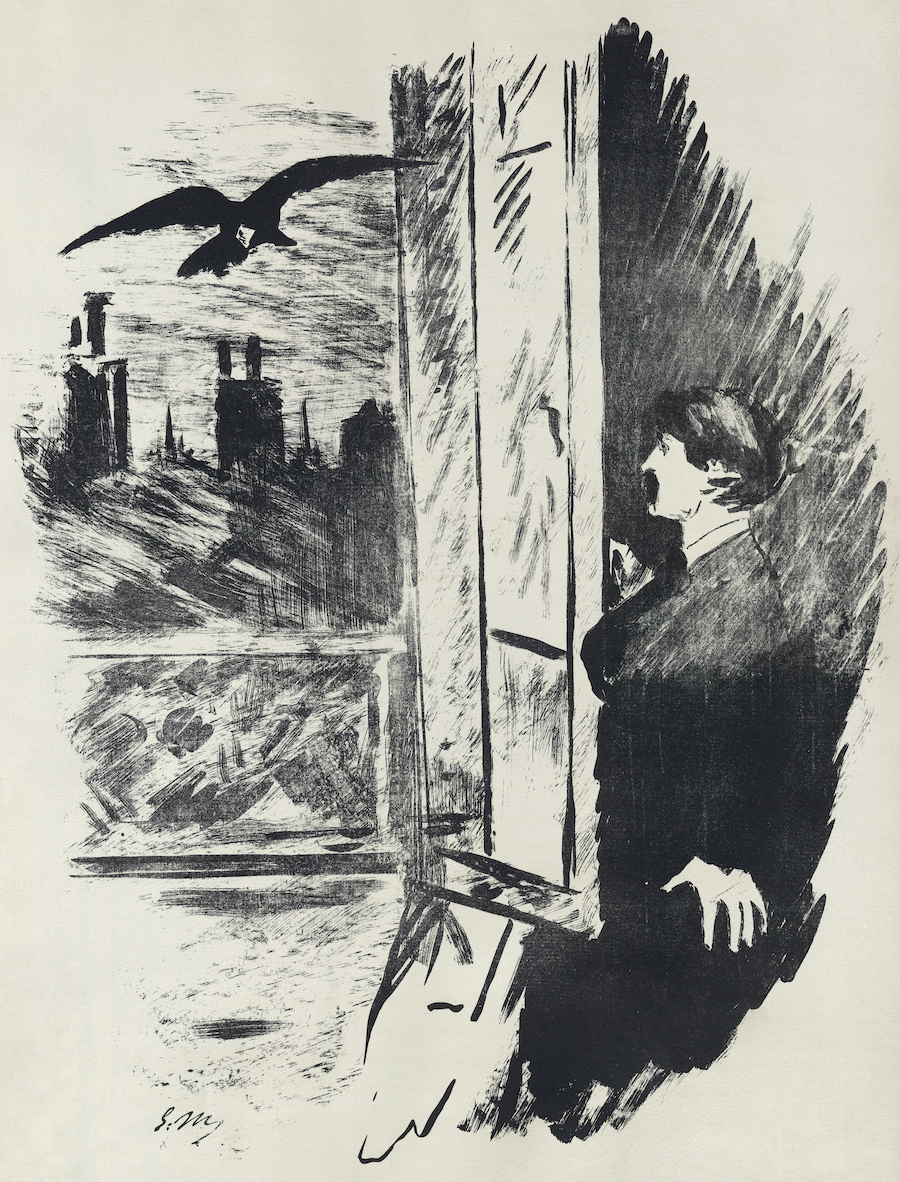

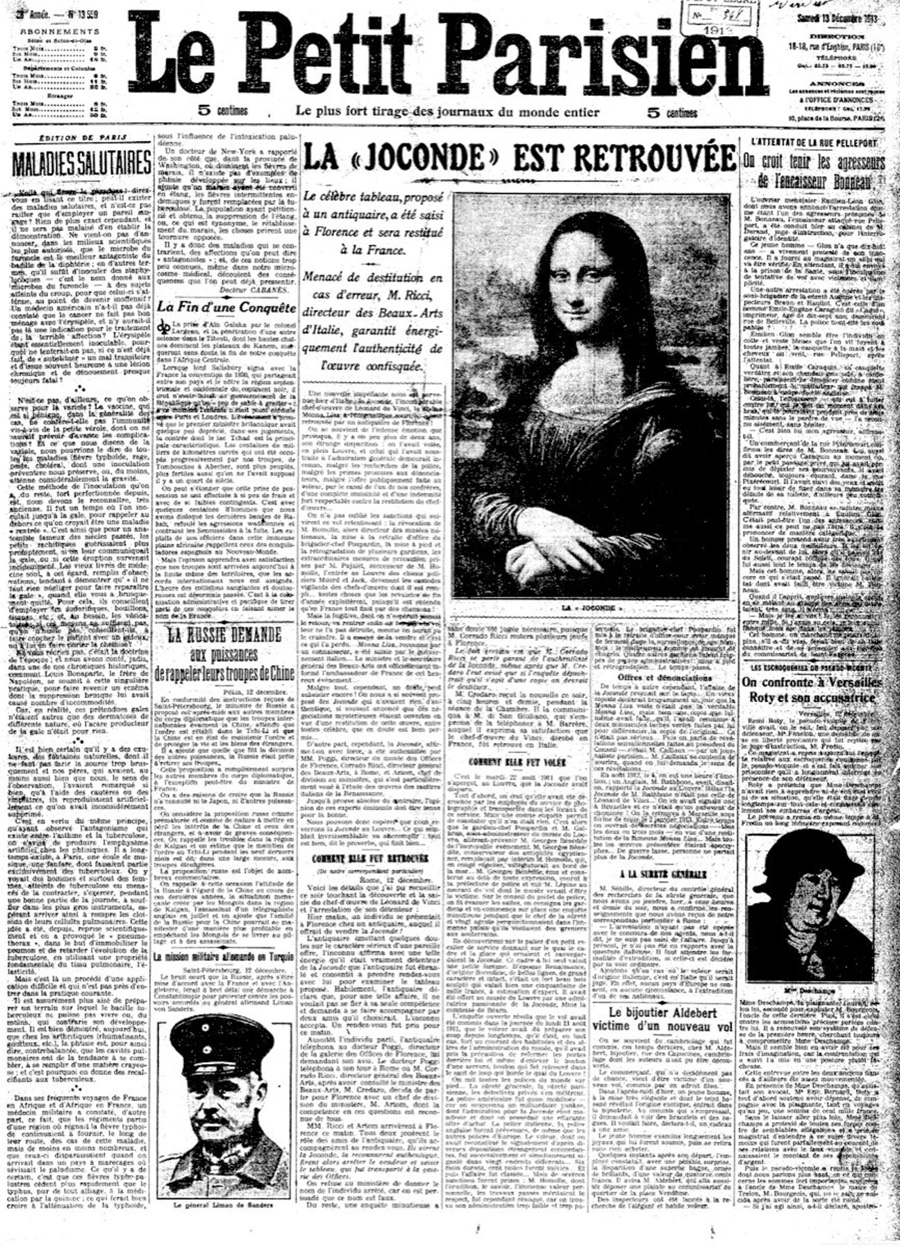

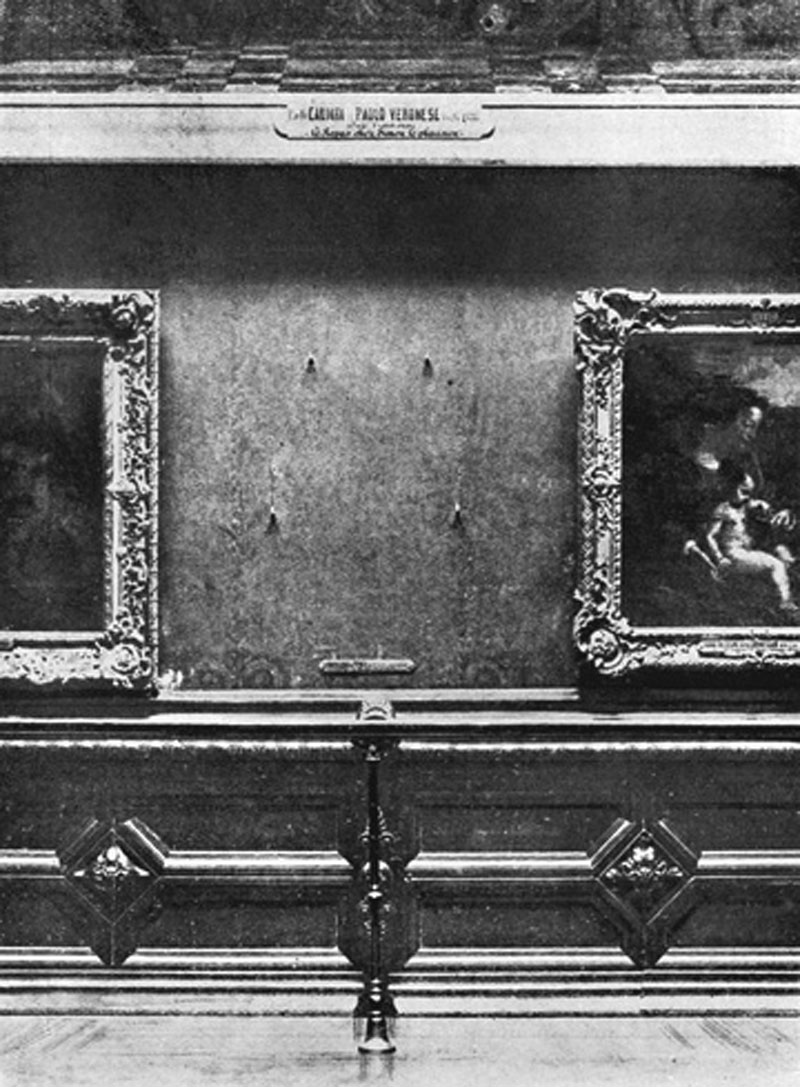

If you visit the Louvre today, you’ll notice two phenomena in particular: the omnipresence of security, and the throng of visitors obscuring the Mona Lisa. If you’d visited just over a century ago, neither would have been the case. And if you happened to visit on August 22nd, 1911, you wouldn’t have encountered Leonardo’s famed portrait at all. That morning, writes Messy Nessy, “Parisian artist Louis Béroud, famous for painting and selling his copies of famous artworks, walked into the Louvre to begin a copy of the Mona Lisa. When he arrived into the Salon Carré where the Da Vinci had been on display for the past five years, he found four iron pegs and no painting.”

Béroud “theatrically alerted the sleepy guards who fumbled around for several hours under the assumption the painting might have been borrowed for cleaning or photographing, until it was finally confirmed the Mona Lisa had been stolen.”

The immediate measures taken: “The Louvre was closed for an entire week, museum administrators lost their jobs, the French borders were closed as every ship and train was searched and a reward of 25,000 francs was announced for the painting.”

High on the list of suspects, thanks to the word of an art thief not involved in the heist named Joseph Géry Pieret: none other than Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire. Confessing to his habit of purloining small items from the Louvre, which then took no great pains to protect the cultural assets within its walls, Pieret informed the police that he had sold a couple of small Iberian statues to a “painter-friend.” Pieret, writes Artsy’s Ian Shank, “had left a clue — a nom de plume in one of his published confessions, pulled straight from the writings of avant-garde poet Apollinaire. (As police would later discover, Pieret was in fact the writer’s former secretary.)”

As the powers that be knew, “Apollinaire was a devout member of Picasso’s modernist entourage la bande de Picasso — a group of artistic firebrands also known around town as the ‘Wild Men of Paris.’ Here, police believed, was a ring of art thieves sophisticated enough to swipe the Mona Lisa.” Though the Spanish-born painter and Italian-born poet had nothing to do with the theft of the Mona Lisa, Picasso had indeed bought those stolen sculptures from Pieret, and in a panic nearly threw them into the Seine.

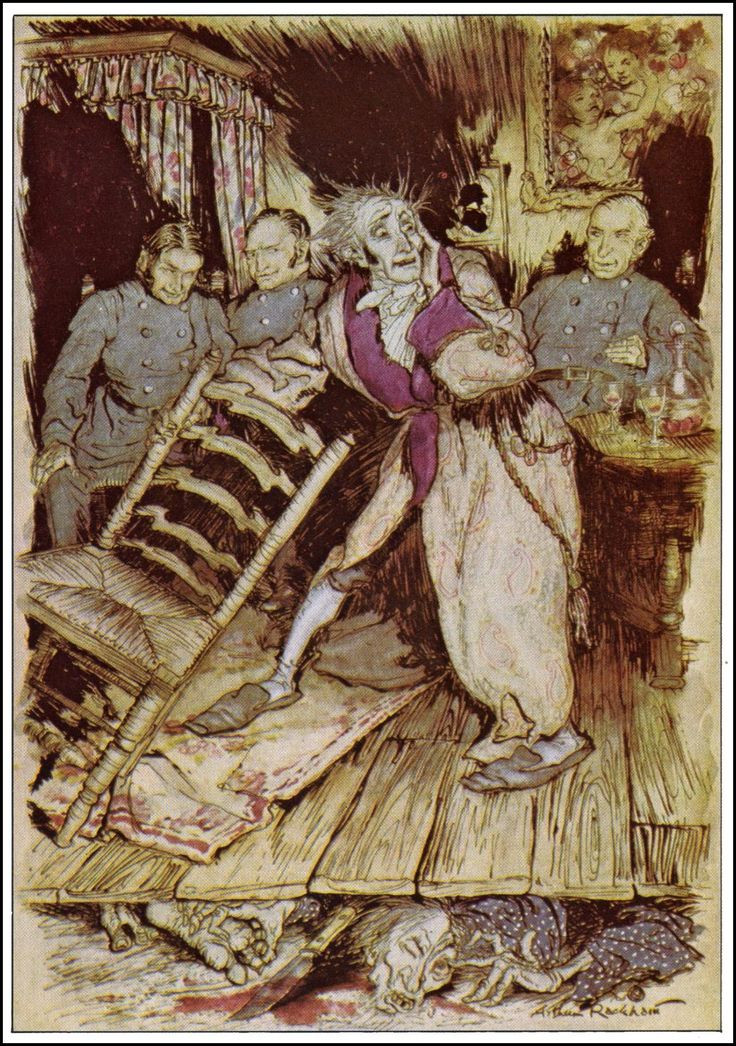

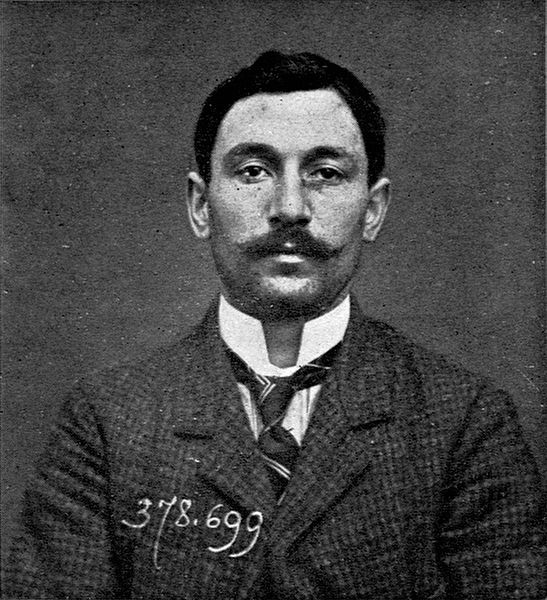

“Apollinaire confessed to everything,” writes Shank, while Picasso “wept openly in court, hysterically alleging at one point that he had never even met Apollinaire. Deluged with contradictory and nonsensical testimony the presiding Judge Henri Drioux threw out the case, ultimately dismissing both men with little more than a stern admonition.” Two years later, the identity of the real Mona Lisa thief came to light: a Louvre employee named Vincenzo Peruggia (shown right above), who had easily smuggled the canvas out and kept it in a trunk until such time — so he insisted — as he could repatriate the masterpiece to its, and his, homeland.

All this makes for an entertaining chapter in the history of art crime, but if you still believe that Picasso must have had a hand in the Mona Lisa’s disappearance, have a look at “All the Evidence That Picasso Actually Stole the Mona Lisa.” Compiled by the Huffington Post’s Sara Boboltz, the list includes such facts as “He was living in France at the time,” “He’d technically purchased stolen artworks before” — those little Iberian sculptures — and “He loved art, duh.” None could deny that last point, just as none could deny the Mona Lisa’s enduring status as something of a Holy Grail for art thieves. But what modern-day Peruggia — or Picasso, or Apollinaire, or as some theories hold, Béroud — would dare make an attempt on it now?

via Mental Floss/Artsy/Messy Nessy

Related Content:

The Adoration of the Mona Lisa Begins with Theft

Mona Lisa Selfie: A Montage of Social Media Photos Taken at the Louvre and Put on Instagram

Original Portrait of the Mona Lisa Found Beneath the Paint Layers of da Vinci’s Masterpiece

The Postcards That Picasso Illustrated and Sent to Jean Cocteau, Apollinaire & Gertrude Stein

Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.