By now we’ve all heard of Marie Kondo, the Japanese home-organization guru whose book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up became an international bestseller in 2011. Her advice about how to straighten up the home, branded the “KonMari” method, has more recently landed her that brass ring of early 21st-century fame, her own Netflix series. A few years ago we featured her tips for dealing with your piles of reading material, which, like all her advice, are based on discarding the items that no longer “spark joy” in one’s life. These include “Take your books off the shelves,” “Make sure to touch each one,” and that you’ll never read the books you mean to read “sometime.”

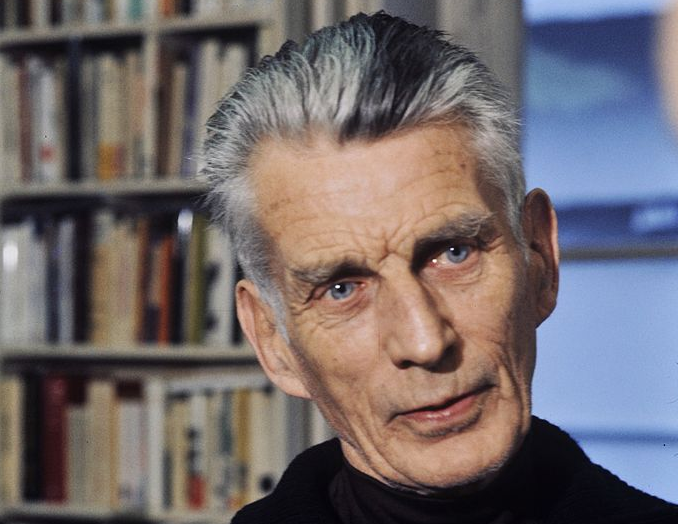

But as a big a fan base as Kondo now commands around the world, not everyone agrees with her methods, especially when she applies them to the bookshelf. “Do NOT listen to Marie Kondo or Konmari in relation to books,” the novelist Anakana Schofield posted to Twitter earlier this month. “Fill your apartment & world with them. I don’t give a shite if you throw out your knickers and Tupperware but the woman is very misguided about BOOKS. Every human needs a v extensive library not clean, boring shelves.” Furthermore, “the notion that books should spark joy is a LUDICROUS one. I have said it a hundred times: Literature does not exist only to comfort and placate us. It should disturb + perturb us. Life is disturbing.”

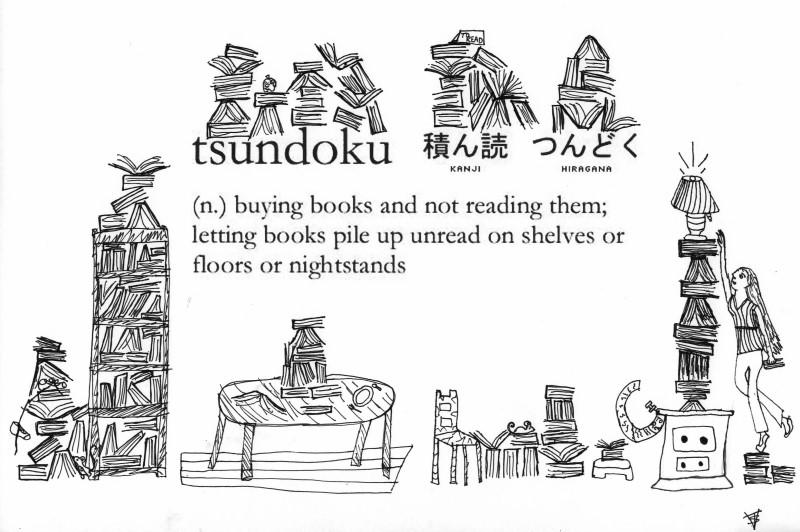

Washington Post book critic Ron Charles criticizes Kondo’s book policy from a different angle. “I have a single cabinet full of chipped mugs, but I have a house full of books — thousands of books. To take every single book into my hands and test it for sparkiness would take years. And during that time, so many more books will pour in.” That phenomenon will be familiar to readers of Open Culture, since we’ve previously featured tsundoku, a punnish Japanese compound word that means the books that amass unread here and there in one’s home.

Though they might have emerged from the same wider culture, the KonMari method and the concept of tsundoku could hardly be more directly opposed. But now that Schofield, Charles, and many others have voiced their perspectives, the battle lines are drawn: must books spark joy in the moment to earn their keep, or can they be allowed to pile up in the name of potential future usefulness — or at least useful disturbance and perturbation?

Related Content:

Change Your Life! Learn the Japanese Art of Decluttering, Organizing & Tidying Things Up

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.