Vincent van Gogh never went to Japan, but he did spend quite a bit of time in Arles, which he considered the Japan of France. What made him think of the place that way had to do entirely with aesthetics. The Netherlands-born painter had moved to Paris in 1886, but two years later he set off for the south of France in hopes of finding real-life equivalents of the “clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects” of Japanese prints. These days, we’ve all seen at least a few examples of that kind of art and can imagine more or less exactly what he was talking about. But how did the man who painted Sunflowers and The Starry Night come to draw such inspiration from what must have felt like such exotic art of such distant a provenance?

“There was huge admiration for all things Japanese in the second half of the nineteenth century,” says the Van Gogh Museum’s visual essay on the painter’s relationship with Japan. “Very few artists in the Netherlands studied Japanese art. In Paris, by contrast, it was all the rage. So it was there that Vincent discovered the impact Oriental art was having on the West, when he decided to modernise his own art.”

Having got a deal on about 660 Japanese woodcuts in the winter of 1886–87, apparently with an intent to trade them, he ultimately held on to them, copied them, and even used their elements as backgrounds for his own portraits.

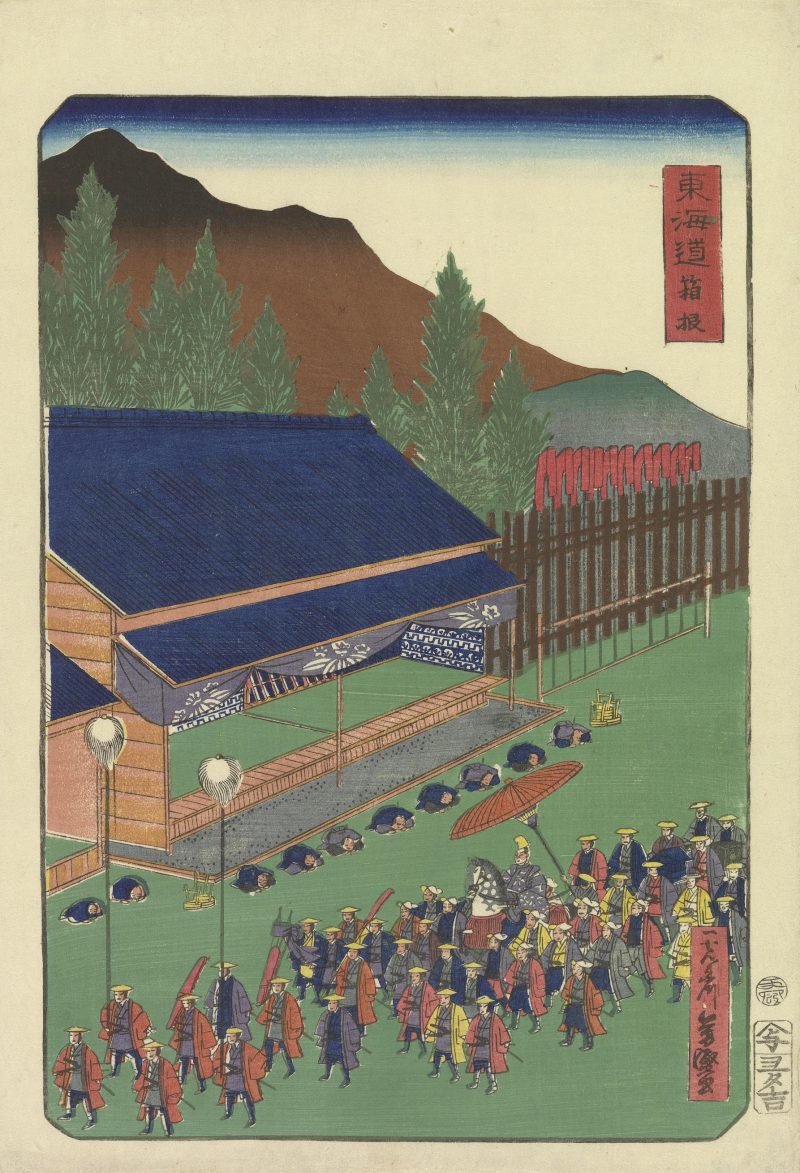

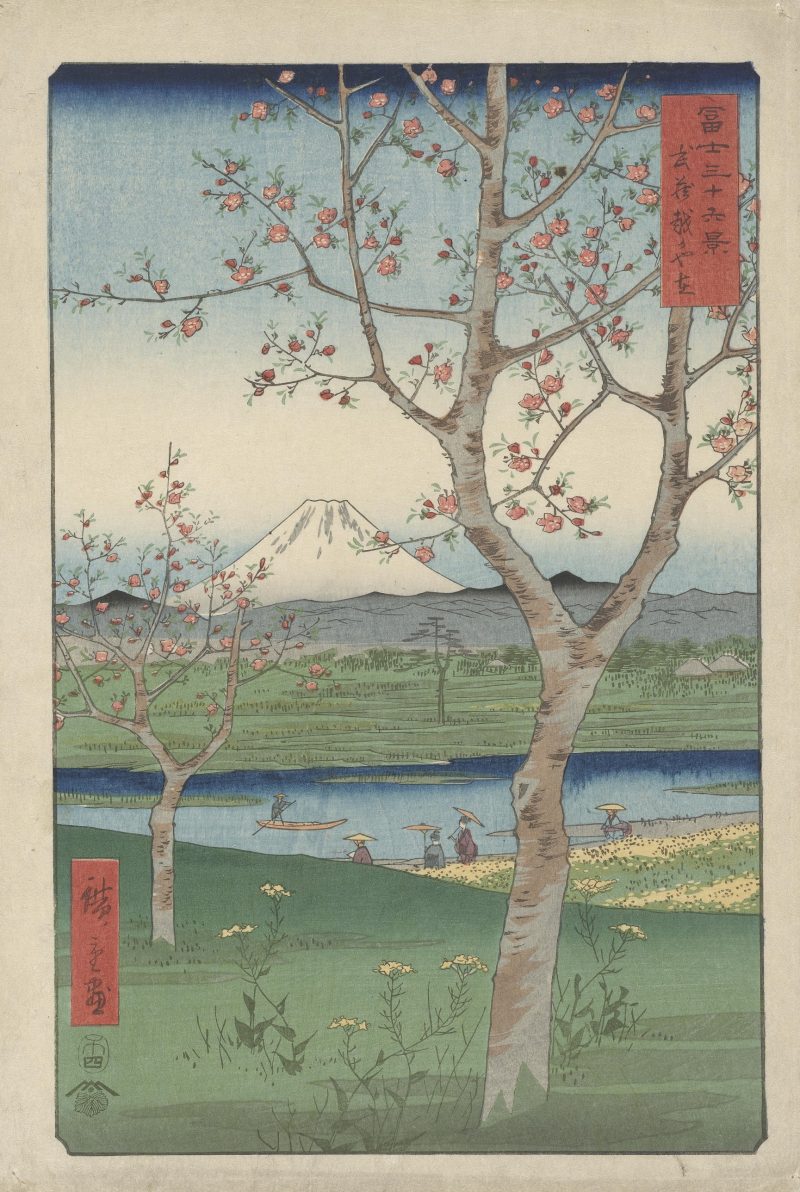

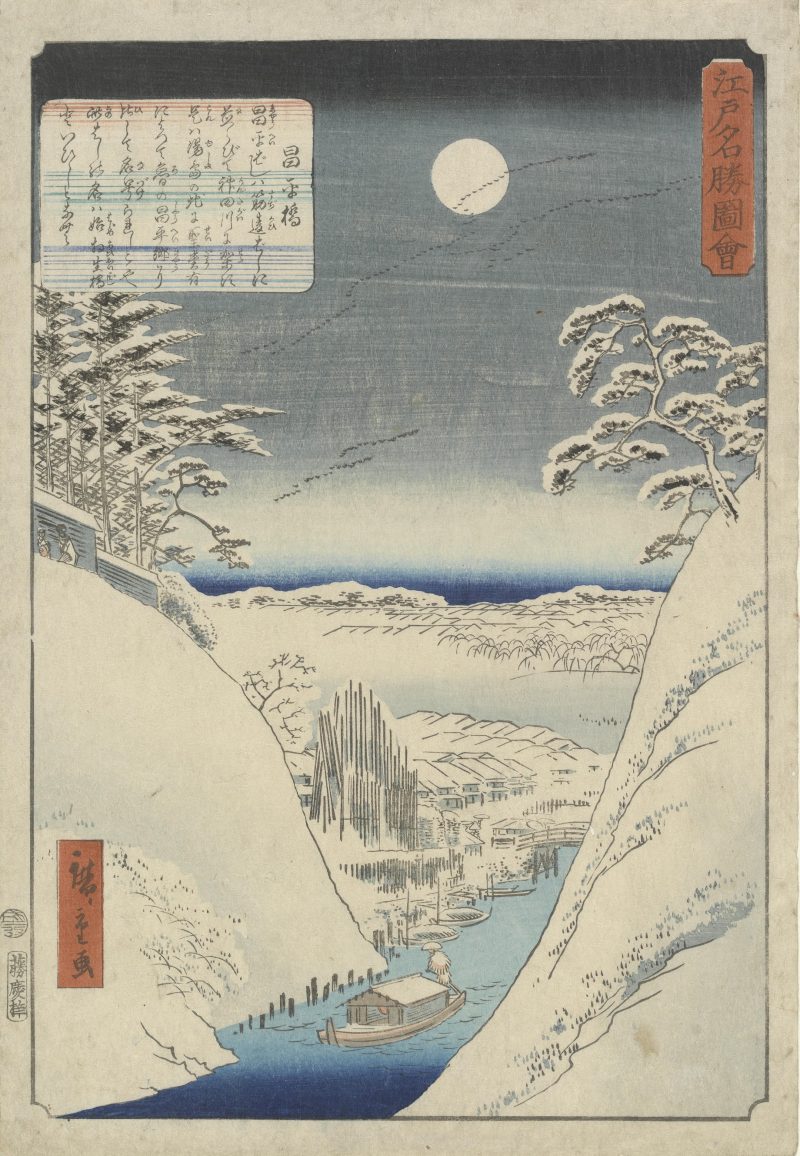

“My studio’s quite tolerable,” he wrote to his brother Theo, “mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting. You know, those little female figures in gardens or on the shore, horsemen, flowers, gnarled thorn branches.” More than a diversion, he saw in their radical difference from the rigorously realistic, convention-bound traditional European painting a way toward “the art of the future,” which he was convinced “had to be colourful and joyous, just like Japanese printmaking.” As he developed what he called a “Japanese eye” while living in Arles, “his compositions became flatter, more intense in colour, with clear lines and decorative patterns.”

The Van Gogh Museum has digitized and made available to download Van Gogh’s Japanese art collection, or at least most of them: you can read about the hundred or so “missing” works here, and you can view the 500 the museum has retained here. Every time you reload the front page, the selection it presents reshuffles; otherwise, you can browse the collection by subject, person and institution, technique, object type, and style. Some of the best-represented categories include landscape, actor print, spring, and female beauty. Whether the Japan-inspired Van Gogh (or colleagues who shared his interest, chiefly Paul Gauguin) succeeded in creating the art of the future is up to art historians to debate, but no one who sees his collection of Japanese art will ever be able to unsee its influence on his own work. Not that Van Gogh didn’t admit it himself: “All my work,” he wrote in a later letter to Theo, “is based to some extent on Japanese art.”

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution

Simon Schama Presents Van Gogh and the Beginning of Modern Art

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.