What do you do after you’ve helped create one of the “first anti-heroes in Western comics”; pioneered the underground comics industry and heavy metal album covers; won the enduring admiration of Federico Fellini, Stan Lee, and Hayao Miyazaki; and brought your distinctive creative style to the look of sci-fi classics like Blade Runner, Alien, Tron, and The Abyss?

Sit back, have a coffee, and design a series of ads for Maxwell House. Why not? You’re Moebius. You can draw whatever you want. No one’s going to accuse Alejandro Jodorowsky’s partner in the legendary never-made Dune film and The Incal comics of selling out—not when contemporary comic art, science fiction, and fantasy could hardly have existed without him.

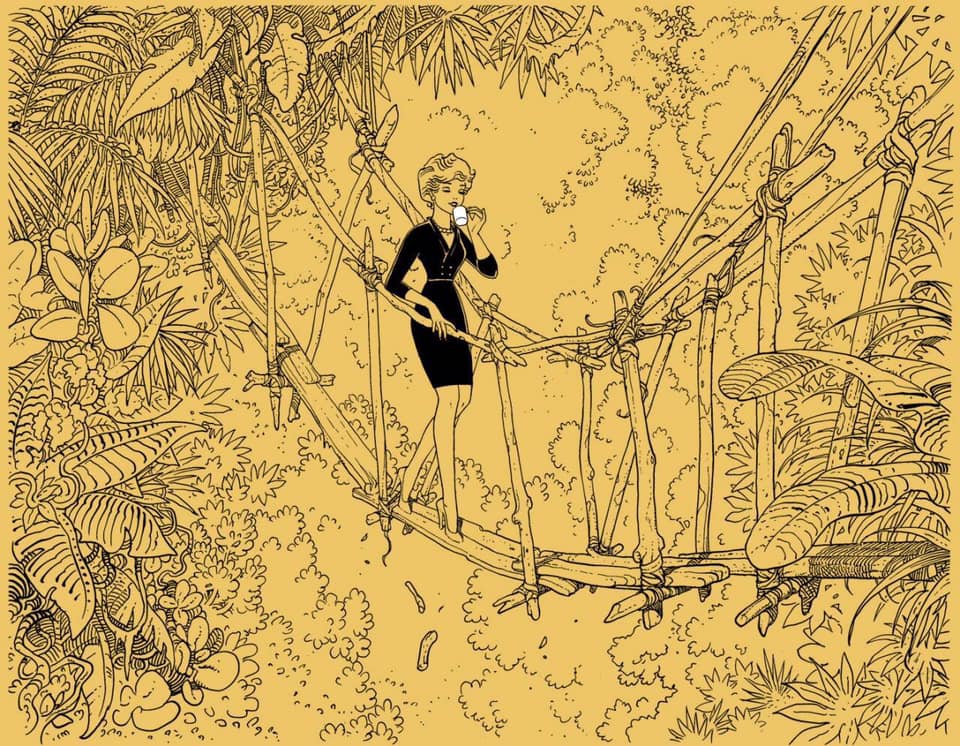

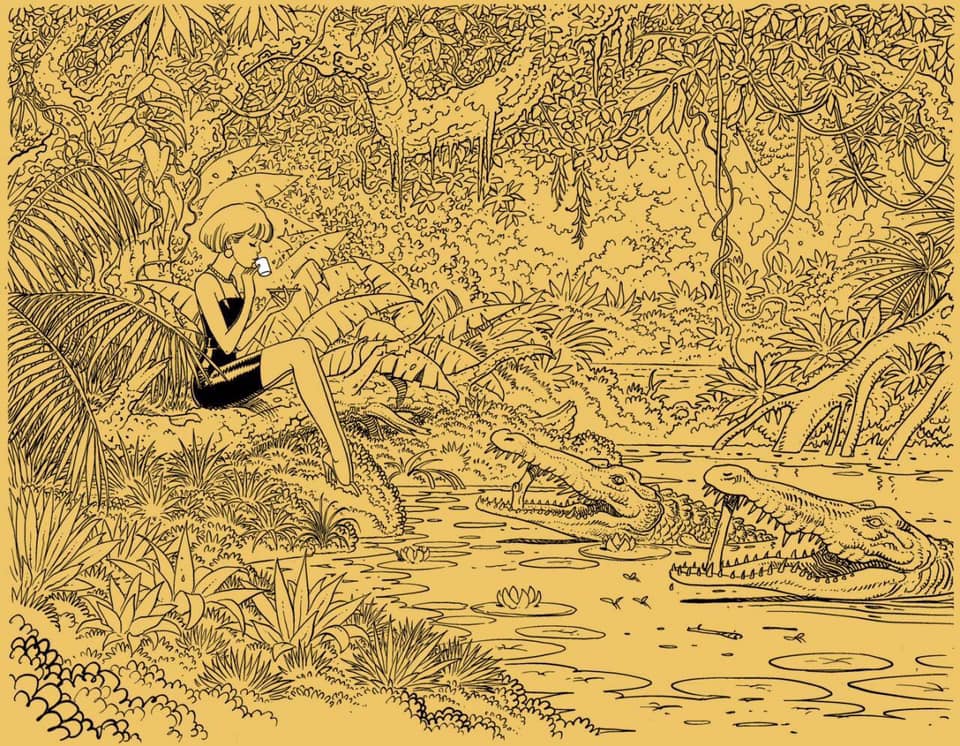

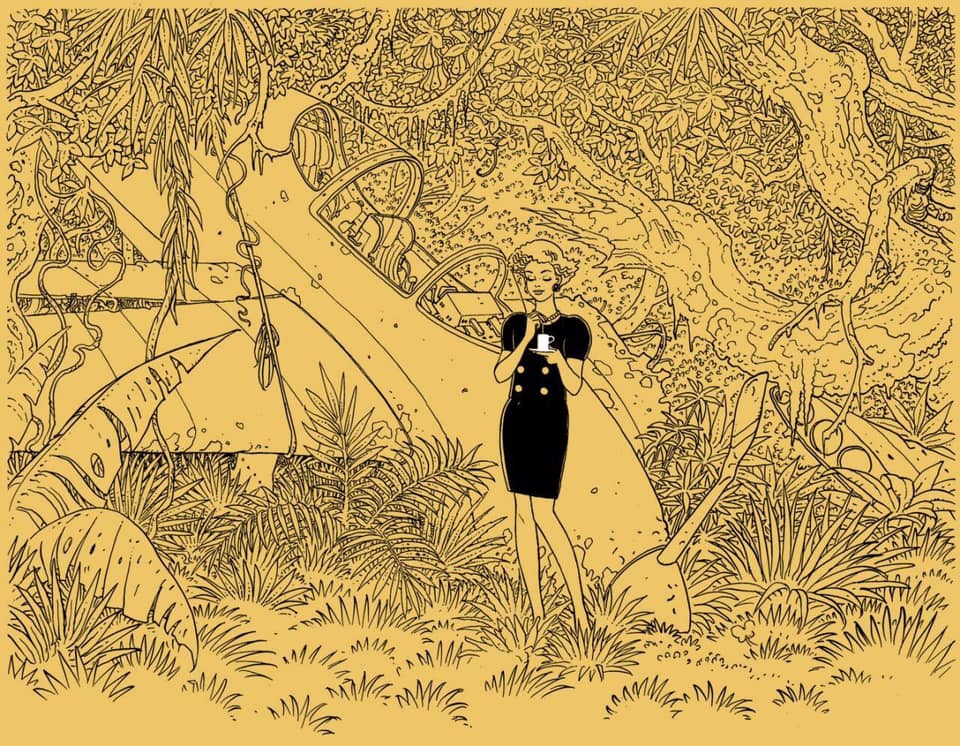

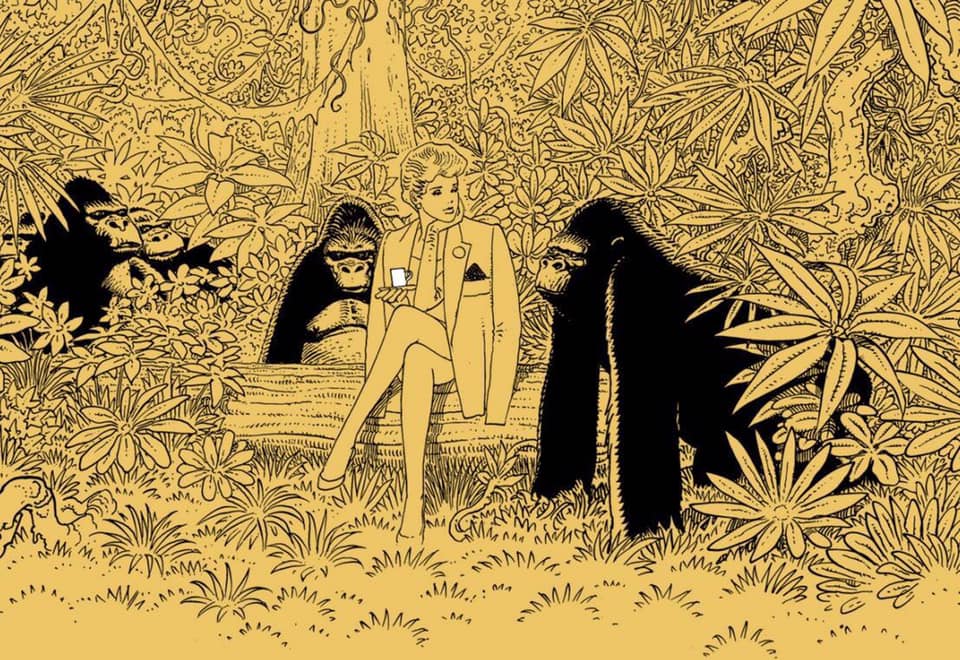

“Probably the most important fantasy comic artist of all time,” as Art Futura dubs him, the man originally known by his birth name Jean Giraud began his career as an illustrator for the youth press Fleurus, who were the first in France to publish fellow bande dessinées artist Herge’s Adventures of Tintin. The Maxwell House ads here, drawn in 1989, recall those early days of Franco-Belgian comic art, when adventurers raced around the colonies, braving wild animals and surly natives.

Moebius’ confident hand leaves a signature in the dense patterns of the foliage and slender jawline of the elegant, coffee-sipping damsel, who does not seem remotely in distress, downed plane and curious gorillas notwithstanding. But the settings are just as reminiscent of Tintin’s juvenile conceptions of the Amazon and “darkest Africa,” though Moebius leaves out the swashbucklers and ugly native caricatures.

Giraud’s own travels took him through Mexico—where he joined his mother as a teenager and saw for the first time the magnificent Western landscapes he had always dreamed of—and through Algeria, where he worked as an illustrator for the French army magazine while finishing his military service. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he portrayed non-European nations and people with sympathy and respect.

Though he first took the name Moebius in 1974 in order to pursue more fantasy-oriented work after drawing the Western Blueberry for over a decade, some of Giraud’s ‘70s comic stories under the name drew upon real events, like the murder of a North African immigrant, Wounded Knee, and the famous speech of Chief Seattle.

The Maxwell House panels keep things light and sweet, so to speak, though where the cream and sugar might be hiding is anyone’s guess. The heroine of the series, named Tatiana, is “a self-possessed and fashionable young woman who happens to find herself alone on a desert jungle island or the like,” as Martin Schneider writes at Dangerous Minds. Unperturbed, she takes more interest in her coffee than the wildness around her.

At Dangerous Minds you’ll find alternate unused images and the ad campaign’s droll captions describing Tatiana taking coffee breaks from some mundane errand or chore. The commentary, though amusing, is hardly necessary. We can imagine dozens of stories embedded in each panel. The ability to create such complex and evocative illustrations, every one a world within a world, has always set Moebius ahead of his peers and many imitators.

via TripWire/Dangerous Minds

Related Content:

Watch Groundbreaking Comic Artist Mœbius Draw His Characters in Real Time

Behold Moebius’ Many Psychedelic Illustrations of Jimi Hendrix

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness