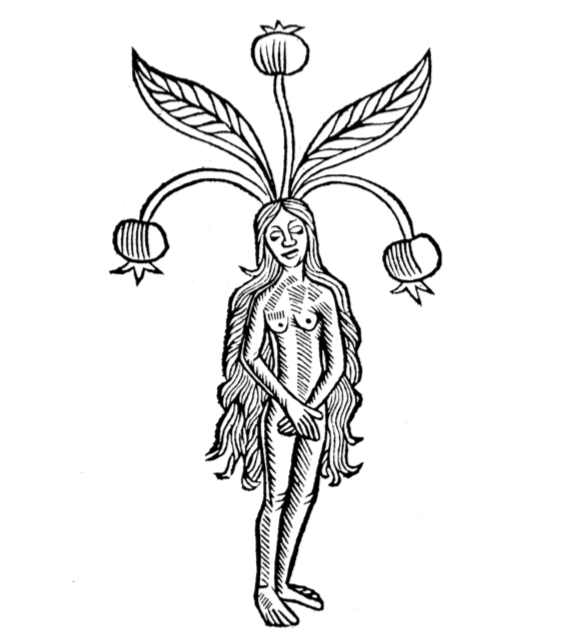

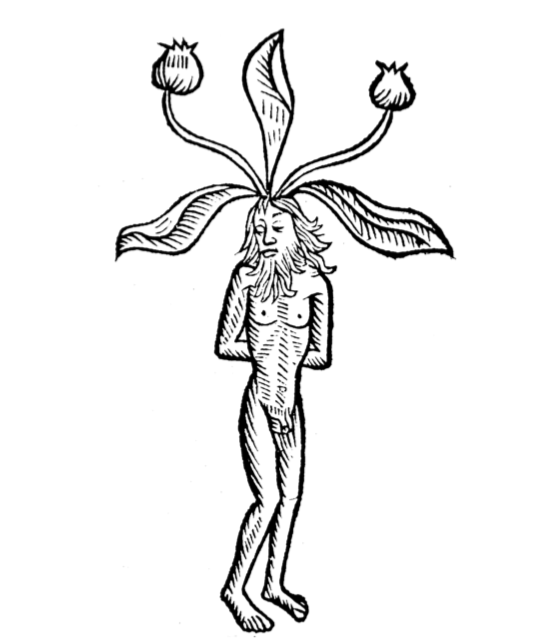

One can only color so many floral-trimmed affirmations before one begins to crave something slightly more perverse. An emaciated, naked, anthropomorphized mandrake root, say or…

Thy wish is our command, but be prepared to hustle, because today is the final day of Color Our Collections, a compellingly democratic initiative on the part of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Since 2016, the Academy has made an annual practice of inviting other libraries, archives, and cultural institutions around the world to upload PDF coloring pages based on their collections for the public’s free download.

This year 113 institutions took the bait.

Our host, the New York Academy of Medicine kicks things off with the aforementioned mandrakes, and then some.

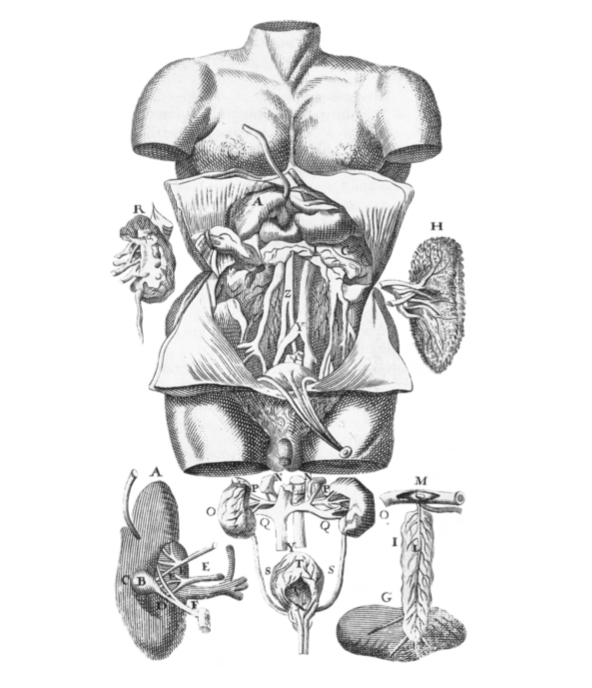

Medical subjects are a popular theme here. You’ll find plenty of organs and other relevant details to color, compliments of Boston’s Countway Library’s Center for the History of Medicine, London’s Royal College of Physicians, and the Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (aka the Mütter Museum).

The coloring book of the Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center at the Davenport Public Library is a bit more all-ages. They certainly remind me of my childhood. The work of native son, Patrick J. Costello, above, figures heavily here. Either he deserves a lot of credit for developing the School House Rock aesthetic, or he was one of a number of hard working illustrators tapping into the cartoon‑y, thick-nibbed zeitgeist

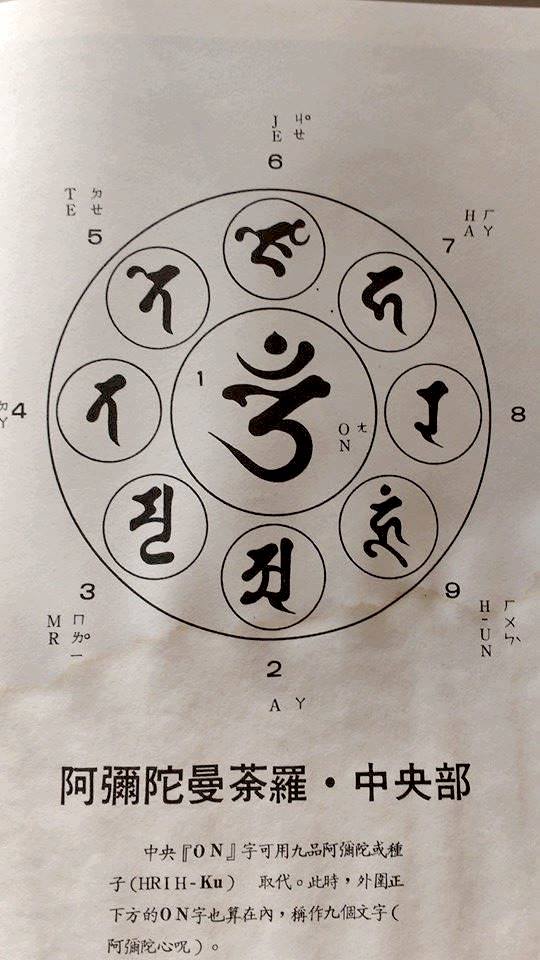

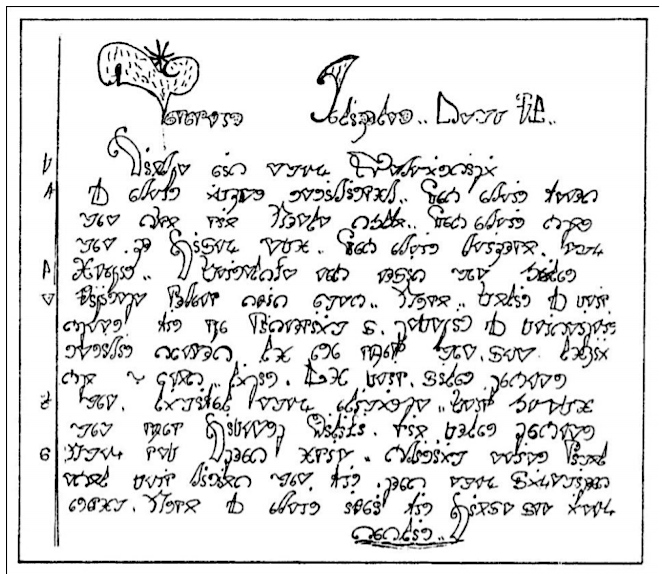

The Andover-Harvard Theological Library’s coloring book has some divine options for those who would use their coloring pages as DIY 16th-century bookplates or alphabet primers.

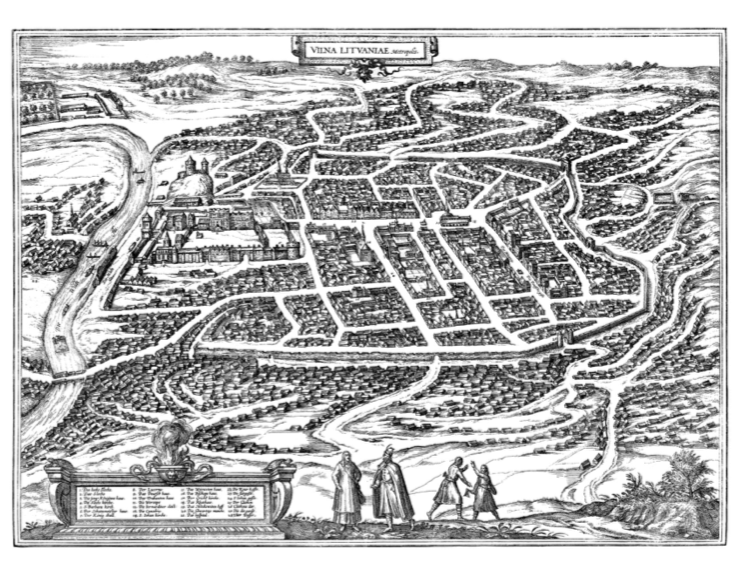

Those who need something more complex will appreciate the intricate maps of the Lithuanian Art Museum’s coloring book. Coloring Franz Hogenberg’s 1581 map of Vilnius is the emotional equivalent of walking the labyrinth for god knows how many hours.

As befits a content website-cum-digital-National-Library, the Memoria Chilena Coloring Book 2019 has something for every taste: flayed anatomical studies, 1940’s fashions, curious kitty cats, and a heaping helping of jesters.

Check out all your options here.

Once you’ve had your way with the Crayolas, please share your creations with the world, using the hashtag #ColorOurCollections.

Participating Institutions 2019

The New York Academy of Medicine Library

Royal College of Physicians, London

OHSU Historical Collections & Archives

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Special Collections

Swarthmore College Libraries

South Carolina State Library

Shenandoah County Library, Truban Archives

Biblioteca de la Universidad de Zaragoza

Christ’s College Library, Cambridge

Tower Hill Botanic Garden

University of Waterloo Special Collections & Archives

Wageningen University & Research

Brunel University Special Collections

Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

Washington State Library

Saint Francis de Sales Parish United by the Most Blessed Sacrament Parish History Archives

Getty Research Institute

Auckland Museum

Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Collections

Seton Hall University Libraries

Bibliotheque interuniversitaire de Sante, Paris

Digital Library at Villanova University

West Virginia and Regional History Center

Bass Library, Yale University Library

University of Kansas Libraries

Medical Heritage Library

The Ohio State University Health Sciences Library

University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

Rutgers University Special Collections and University Archives

University of British Columbia Library

National Library of Medicine

Science History Institute

Ricker Library of Architecture and Art at the University of Illinois

Chautauqua Institution Archives

Bibliotheque et Archives nationales du Quebec

The LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden

Auburn University Special Collections and Archives

Open Museum, Academia Sinica Center for Digital Cultures

Les Champs Libres

Lithuanian Art Museum

Memoria Chilena

Barret Library, Rhodes College

Wales Higher Education Libraries Forum (WHELF)

Royal Anthropological Institute

Delaware Museum of Natural History

James Madison University Libraries

Utah State University Libraries Special Collections & Archives

Stevens Institute of Technology / Archives & Special Collections

Waring Historical Library of the Medical University of South Carolina

Bernard Becker Medical Library at Washington University in St. Louis

University of Puget Sound

Drexel University College of Medicine Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections

Queens’ College Library, Cambridge

Stadtbibliothek Koeln

Andover-Harvard Theological Library

Rare Book and Manuscript CRAI Library at University of Barcelona

Newberry Library

Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Lambeth Palace Library

Folger Shakespeare Library

University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections

John J. Burns Library

Biodiversity Heritage Library

The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa Digital Library

Tennessee State Museum

Center for the History of Medicine, Countway LIbrary

Russian State Library

South Carolina Historical Society

Library Company of Philadelphia

The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary

Pratt Institute Archives

The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis

Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine, University of Minnesota Libraries

Washington University Libraries Julian Edison Department of Special Collections

Libraries and Cultural Resources, University of Calgary

Leonard H. Axe Library, Pittsburg State University

Susquehanna University, Blough-Weis Library

Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center, Davenport Public Library

Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogy

Findlay-Hancock County Public Library

Northern Illinois University

Escuela Superior de Artes de Yucatan

Lake County Public Library

United Nations Library Geneva

Jeleniorskie Centrum Informacji i Edukacji Regionalnej Ksiaznica Karkonoska

Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago

Grand Portage National Monument Archives Collection

Jagiellonian Library

Botanical Research Institute of Texas

University of North Texas Libraries

Lehigh University Libraries Special Collections

Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Massachusetts General Hospital Archives & Special Collections

Clark Special Collections, McDermott Library, USAFA

Bibliotheque nationale de France

Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art Archive & Library

Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design

British Library

Western University Archives and Special Collections

Europeana

Denver Botanic Gardens

MedChi, The Maryland State Medical Society

Grinnell College Libraries

University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC)

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

National Library of Russia

Eastern Kentucky University Special Collections & Archives

Numelyo

Louisiana State University Special Collections

New York State Library

North Carolina Pottery Center

Royal Horticultural Society Libraries

Library of Virginia

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. See her onstage in New York City this Monday as host of Theater of the Apes book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.