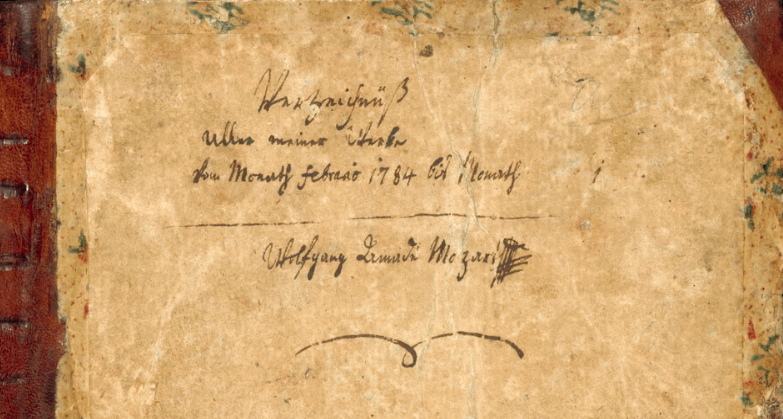

What place does the paper book have in our increasingly all-digital present? While some utilitarian arguments once marshaled in its favor (“You can read them in the bathtub” and the like) have fallen into disuse, other, more aesthetically focused arguments have arisen: that a work in print, for example, can achieve a state of beauty as an object in and of itself, the way a file on a laptop, phone, or reader never can. In a sense, this case for the paper book in the 21st century comes back around to the case for the paper book from the 12th century and even earlier, the age of the illuminated manuscript.

Bookmakers back then had to concentrate on prestige products, given that they couldn’t make books in anything like the numbers even the humblest, most antiquated printing operation can run off today.

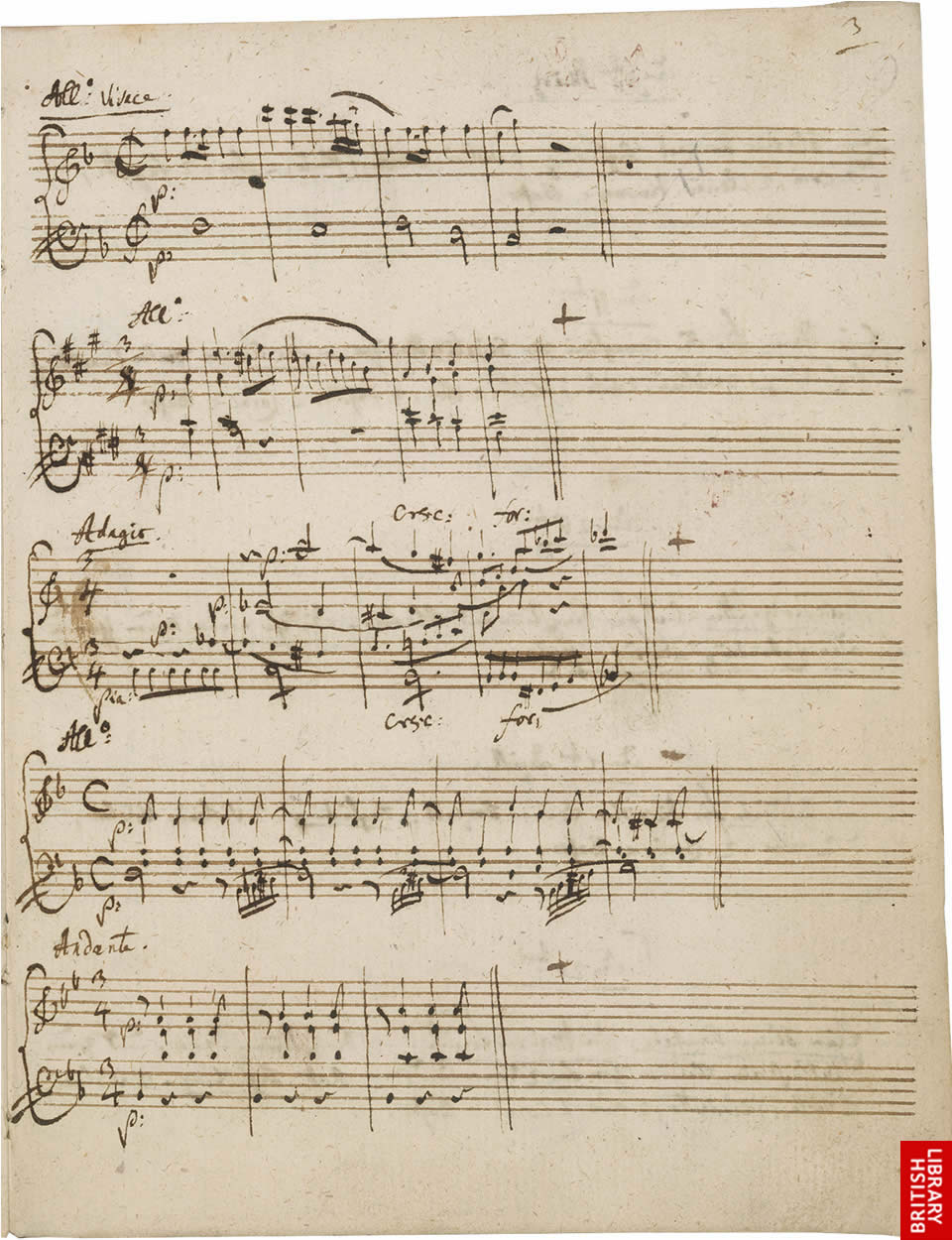

In the video above, the Getty Museum reveals the painstaking physical process behind the medieval illuminated manuscript: the sourcing, soaking, and stretching of animal skin for the parchment; the conversion of feathers into the quills and nuts into the ink with which scribes would write the text; the application of gold leaf and other colors by the illuminator as they drew in their designs; and the sewing of the binding before encasing the whole package tightly between clasped leather covers.

Some illuminated manuscripts also bear elaborate cover designs sculpted of precious metal, but even without those, these elaborate books — what with all the art and craft that went into them, not to mention all those pricey materials — came out even more valuable, at the time, than even the most coveted laptop, phone, reader, or other consumer electronic device today. Most of us in the developed world can now buy one of those, but the non-institutional patrons willing and able to commission the most splendid illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance included mostly “society’s rulers: emperors, kings, dukes, cardinals, and bishops.”

To fully understand the making of the devices we use to read electronically today would require years and years of study, and so there’s something satisfying in the fact that we can grasp so much about the making of illuminated manuscripts with relative ease: see, for example, the two-minute Getty video just above, “The Structure of a Medieval Manuscript.” A fuller understanding of the nature of illuminated manuscripts, both in the sense of their construction and their place in society, makes for a fuller understanding of how rare the chance was to own beautiful books of their kind in their own time — and how much rarer the exact combination of skills needed to create that beauty.

Related Content:

How the Brilliant Colors of Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts Were Made with Alchemy

1,600-Year-Old Illuminated Manuscript of the Aeneid Digitized & Put Online by The Vatican

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.