It is maybe easy for those unfamiliar with the study of religion to reduce the academic discipline to a ponderous exercise—self-serious, obsessed with tradition, rendered suspect by histories of violence and highly implausible, contradictory claims. But this is a mistake. For one thing, as scholar of religion Wilfred Cantwell Smith once wrote, “the study of religion is the study of persons”—quite broadly, he suggests, to study religion is to study humanity: anthropology, sociology, history, art, literature, philosophy, mythology, psychology, etc. Studying religion can also be—contrary to certain stereotypes—a great deal of fun.

In what other scholarly pursuit, after all, can one read Reginald Scot, Esquire’s 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, L. Austine Waddell’s 1805 The Buddhism of Tibet, and J.G. Frazer’s 1894 The Golden Bough, inspiration for T.S. Eliot’s poetry and spiritual ancestor to Joseph Campbell’s popular comparative work The Hero with a Thousand Faces?

But of course, not many an advanced scholar would find him or herself immersed in all of these texts, specializing, as they must, in one particular area. Those of us who are merely curious, however, or insatiably curious, can do as we please in the theology library, thumbing through whatever strikes our fancy.

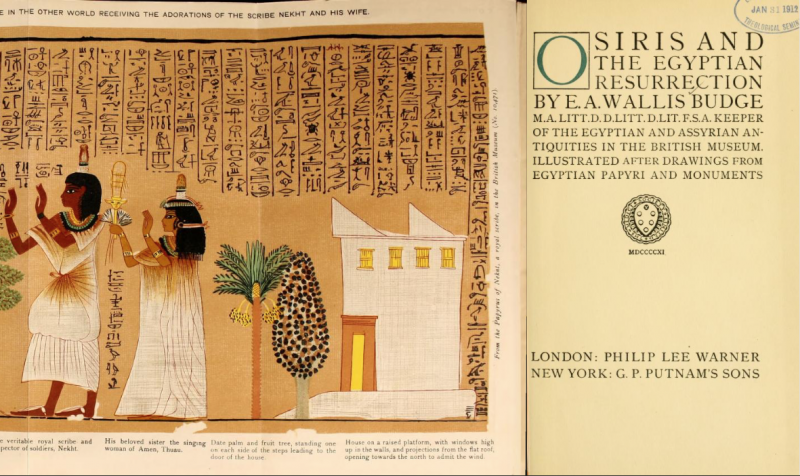

We may do so from the comfort of wherever we can get wifi thanks to Princeton Theological Seminary’s Theological Commons’ project with the Internet Archive, which has digitized over 70,000 texts from the Princeton Theological Seminary Library, spanning hundreds of years and nearly every conceivable religious subject. Yes, there are shelves of hymnals, hardly the kind of thing to generate much interest among any but the most devout or the most deeply-down-a-scholarly-rabbit-hole. But there are also many fascinating gems like Jacob Grimm’s 1882–88 Teutonic Mythology in four volumes (translated into English), like E.A. Wallis Budge’s beautifully illustrated 1911 Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, and like Wesleyan minister Charles Roberts’ 1899 The Zulu-Kafir Language Simplified for Beginners.

Like many texts written by colonial observers and Orientalist scholars, some of these books may tell us as much or more about their authors than about the purported subjects—we encounter in religious scholarship no more nor less bias than in any other field, though piety is given license to take more overt forms. Unfortunately, as Cantwell Smith wrote, “the traditional form of Western scholarship in the study of other men’s religion was that of an impersonal presentation of an ‘it.’” But these outdated views are themselves instructive—as part of a process towards a wider humanist understanding, “the gradual recognition of what was always true in principle, but was not always grasped.”

For students and professional scholars, the Princeton digital library is obviously, well… a godsend. For the merely—or insatiably—curious, it is an open invitation to explore strange new worlds, so to speak, and to realize, again and again, that they’re all the same world, seen in innumerably different ways. In this archive, you’ll find primary texts and commentaries on Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Greek and Egyptian religions, indigenous faiths of all kinds, and, of course, given the source, plenty of Christianity (like the 1606, pre-King James Bible at the top). “The next step,” writes Cantwell Smith, in moving the study of religion forward, “is a dialogue.… If there is listening and mutuality… the culmination of this progress is when ‘we all’ are talking with each other about ‘us.’”

Enter the online Princeton Theological Seminary Library here.

Related Content:

Harvard Launches a Free Online Course to Promote Religious Tolerance & Understanding

Philosophy of Religion: A Free Online Course

Free Online Religion Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness