Image by Farrin Abbott/SLAC, via Flickr Commons

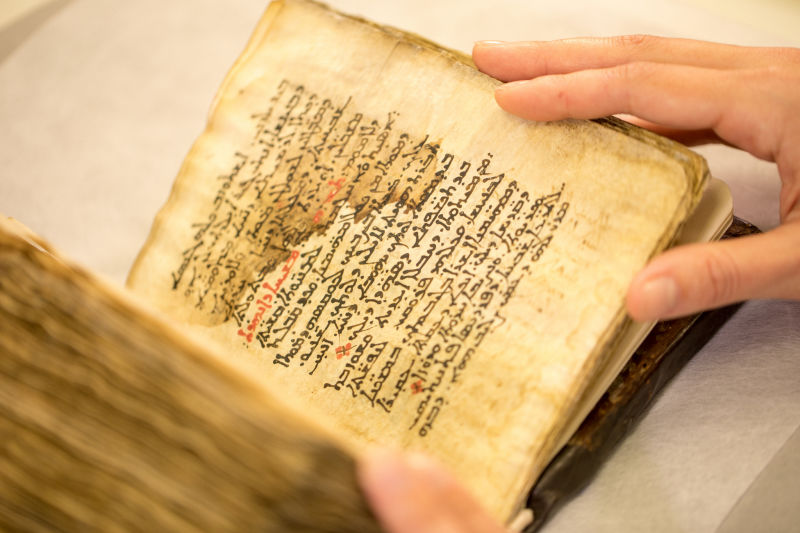

Long before humanity had paper to write on, we had papyrus. Made of the pith of the wetland plant Cyperus papyrus and first used in ancient Egypt, it made for quite a step up in terms of convenience from, say, the stone tablet. And not only could you write on it, you could rewrite on it. In that sense it was less the paper of its day than the first-generation video tape: given the expense of the stuff, it often made sense to erase the content already written on a piece of papyrus in order to record something more timely. But you couldn’t completely obliterate the previous layers of text, a fact that has long held out promise to scholars of ancient history looking to expand their field of primary sources.

The decidedly non-ancient solution: particle accelerators. Researchers at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) recently used one to find the hidden text in what’s now called the Syriac Galen Palimpsest. It contains, somewhere deep in its pages, “On the Mixtures and Powers of Simple Drugs,” an “important pharmaceutical text that would help educate fellow Greek-Roman doctors,” writes Amanda Solliday at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Originally composed by Galen of Pergamon, “an influential physician and a philosopher of early Western medicine,” the work made its way into the 6th-century Islamic world through a translation into a language between Greek and Arabic called Syriac.

Image by Farrin Abbott/SLAC, via Flickr Commons

Alas, “despite the physician’s fame, the most complete surviving version of the translated manuscript was erased and written over with hymns in the 11th century – a common practice at the time.” Palimpsest, the word coined to describe such texts written, erased, and written over on pre-paper materials like papyrus and parchment, has long since had a place in the lexicon as a metaphor for anything long-historied, multi-layered, and fully understandable only with effort. The Stanford team’s effort involved a technique called X‑ray fluorescence (XRF), whose rays “knock out electrons close to the nuclei of metal atoms, and these holes are filled with outer electrons resulting in characteristic X‑ray fluorescence that can be picked up by a sensitive detector.”

Those rays “penetrate through layers of text and calcium, and the hidden Galen text and the newer religious text fluoresce in slightly different ways because their inks contain different combinations of metals such as iron, zinc, mercury and copper.” Each of the leather-bound book’s 26 pages takes ten hours to scan, and the enormous amounts of new data collected will presumably occupy a variety of experts on the ancient world — on the Greek and Islamic civilizations, on their languages, on their medicine — for much longer thereafter. But you do have to wonder: what kind of unimaginably advanced technology will our descendants a millennium and a half years from now be using to read all of the stuff we thought we’d erased?

Related Content:

The Turin Erotic Papyrus: The Oldest Known Depiction of Human Sexuality (Circa 1150 B.C.E.)

Try the Oldest Known Recipe For Toothpaste: From Ancient Egypt, Circa the 4th Century BC

Learn Ancient Greek in 64 Free Lessons: A Free Course from Brandeis & Harvard

Introduction to Ancient Greek History: A Free Online Course from Yale

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.