Why is it, as Brian Gilmore writes at JazzTimes, that “even people who hardly listen to jazz adore this album”? Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue hardly needs an introduction. Many thousands of words have been written about its legendary composition and recording, about the extraordinary ensemble responsible for its existence—Davis, John Coltrane, “Cannonball” Adderley, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb, and a young Bill Evans—and about the year of its release, 1959, a watershed moment in the history of jazz, and of nearly all modern music.

“It’s no longer necessary to remind music lovers that Kind of Blue is essential listening,” argues The Guardian’s John Fordham, “and that everybody who wants to make sense of the music of our time ought to have at least some idea of what’s good about it.” Should your education in Kind of Blue be lacking, you can get caught up on the basics in the Polyphonic video just above, which quickly gets to the heart of Davis’ musical innovation: making the definitive break with bebop and setting the standard for modal jazz, and thus the explosion of free jazz innovations to come.

Where most forms of jazz had built increasingly complex chord changes over which soloists improvised, Davis shifted to using modes (the seven modes of modern music) as the basis for song structure. Without needing to get overly technical with music theory, you can understand immediately upon listening to the album that modal composition allowed Davis and his band to slow down, simplify, and create subtle, complex shifts in mood that can be at once lilting, cool, and kind of… blue. Davis had experimented with blues-based modal forms before. Here, he integrates that knowledge with classical ideas and improvisatory brilliance.

“As is now part of jazz folklore,” notes Fordham, “the New York sessions that produced this remarkable album were completed in a handful of takes over just a few hours, with a minimum of compositional materials.” From there, a revolution. It is “The most exquisitely refined of ambient music,” writes Richard Williams in his definitive monograph The Blue Moment, and the one record many music fans would rescue “from a burning house.” It may be the best-selling jazz album of all time. Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen called it “the Bible.” Quincy Jones called his “orange juice,” because he listens to it every day

“No one could disagree with Williams when he connects this with the developments of John Coltrane,” writes Sholto Byrnes, from his “shocking demolition of the dainty brickwork of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘My Favorite Things,’ ” to his masterpiece A Love Supreme. Its influence, according to Williams, runs through the work of Ornette Coleman Steve Reich, John Cale, the Velvet Underground, James Brown, Sly Stone, Soft Machine, Brian Eno, Moby, and so on and so on. If you’ve never quite understood what makes Kind of Blue so great, get a crash course in the video explainer above. Then sit down and listen to it a few hundred times.

Related Content:

Hear a 65-Hour, Chronological Playlist of Miles Davis’ Revolutionary Jazz Albums

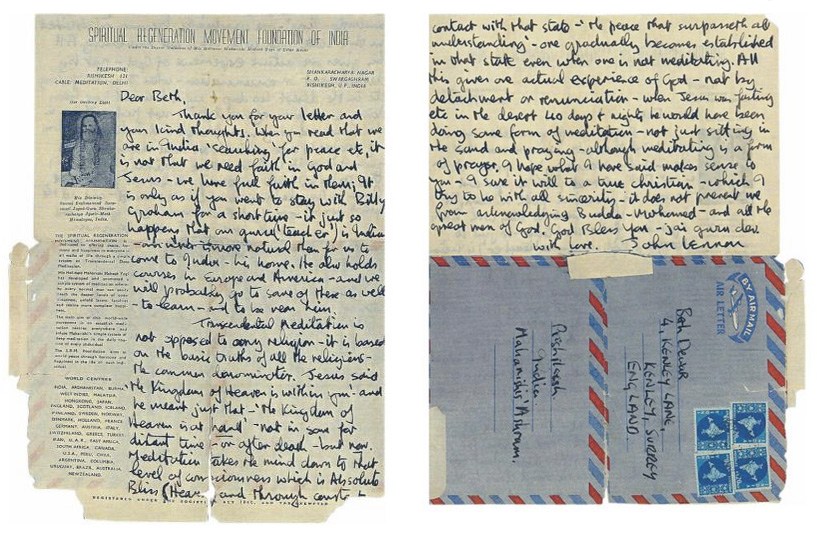

John Coltrane’s Handwritten Outline for His Masterpiece A Love Supreme (1964)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness