Despite their enormous popularity, the enigmatic works of Dutch artist M.C. Escher have not, perhaps, received their due in the high art world. But he is beloved by college-dorm-room-decorators, Haight-Ashbury hippies, mathematicians, doctors, and dentists, who put his art on their walls, says Micky Pillar, former curator of the Escher Museum in The Hague, because “they think it’s a great way of getting people engaged and forgetting about reality.” Mathematical giants Roger Penrose and HSM Coxeter “were dazzled by Escher’s work as students in 1954,” notes The Guardian’s Maev Kennedy. Mick Jagger was a huge fan, though Escher turned him down when asked to draw an album cover, annoyed at being addressed by his first name (Maurits).

Escher, says Ian Dejardin—director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London—“may have been the only person in the world who had never heard of the Rolling Stones.” It wasn’t that he ignored the world around him, but that he focused his career on inventing another one, taking inspiration first from the Italian countryside and cityscapes, after settling in Rome, and later turning to what he called “mental imagery”: the paradoxical portraits, fantastical shifting shapes, and mind-bending patterns, so absorbing that people in waiting rooms forget their discomfort and anxiety when looking at them.

One of the most famous of such works, 1939’s Metamorphosis II, owes its creation to the historical pressures of Italian fascism and the geometric fascinations of Islamic art. After leaving Rome in 1935 as political tensions rose, Escher found himself inspired by his second visit to The Alhambra in Spain. Its “lavish tile work,” as the National Gallery of Art writes, “suggested new directions in the use of color and the flattened patterning of interlocking forms.” So intricate and technically dazzling is the four-meter-long print that it merits an in-depth look at its context and composition.

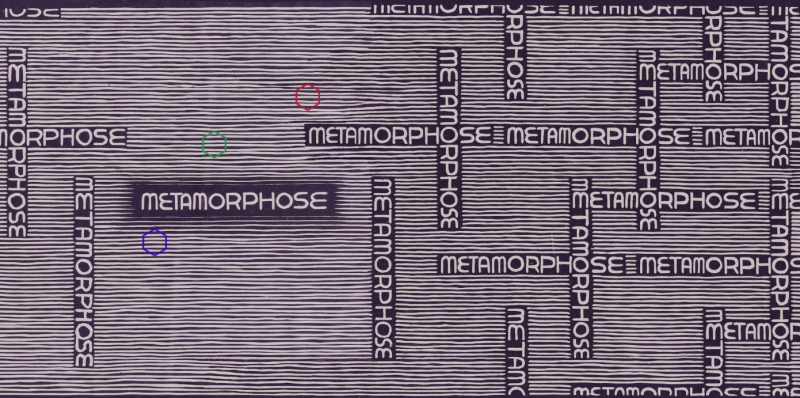

That’s exactly what you’ll find at a new “interactive documentary” on Metamorphosis II, by the makers of a similar feature on Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. The online resource lets users scroll across the print, zooming in to an extraordinary level of detail, or zooming out to see how it transitions section by section, from the word “metamorphose,” to a checkerboard pattern, to lizards, honeycombs, bees, hummingbirds, fish, etc.. Along the way, you can click on little colored hexagons (that transform into cubes) and bring up short articles on Escher’s life and aspects of the work at hand. Each of these featurettes is narrated (in the English version) by British filmmaker and artist Peter Greenaway. Once you open one of these explanatory windows, a navigation tool (above) appears at the bottom of the screen.

We see how the various animals in Escher’s “systematic tessellations,” as he called them, were chosen by virtue of their shape as well as Escher’s interest in their life cycles and methods of organization. “Nature was a source of wondrous beauty for Escher,” the documentary explains. “In his journals and letters, he often wrote about what surprised, amazed or moved him” in the natural world. Some of the Metamorphosis II sections appeared in later works like 1943’s Reptiles. Escher drew attention both to the natural world’s variety and its genius for repeated patterns. But the movement from one animal to the next has nothing to do with zoology.

Escher delighted in playing “mind association games.” We learn that as a child, “he would lie in bed and think of two subjects for which he had to create a logical connection.” In one example he gave, he would attempt to find his way from “a tram conductor to a kitchen chair.” Metamorphosis II gives us a visual representation of such games, mental leaps that challenge our sense of the order of things. The documentary situates this fascinating work in a historical and aesthetic context that allows us to make sense of it while adding to our appreciation for its strangeness, offering several different ways of approaching the work, as well as an invitation to make your own.

One feature, the “Metamorphosis Machine,” lets you choose from a selection of starting and ending patterns. Then it fills in the transformation in the middle. The results are hardly Escher-quality, but they are a fun and accessible way of understanding the work of an artist whose vision can seem forbidding, with its impossible spaces and disorienting transformations. Enter the Metamorphosis II interactive documentary here.

Related Content:

M.C. Escher Cover Art for Great Books by Italo Calvino, George Orwell & Jorge Luis Borges

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness