In the spring of 1934, a young man who wanted to be a writer hitchhiked to Florida to meet his idol, Ernest Hemingway.

Arnold Samuelson was an adventurous 22-year-old. He had been born in a sod house in North Dakota to Norwegian immigrant parents. He completed his coursework in journalism at the University of Minnesota, but refused to pay the $5 fee for a diploma. After college he wanted to see the country, so he packed his violin in a knapsack and thumbed rides out to California. He sold a few stories about his travels to the Sunday Minneapolis Tribune.

In April of ’34 Samuelson was back in Minnesota when he read a story by Hemingway in Cosmopolitan, called “One Trip Across.” The short story would later become part of Hemingway’s fourth novel, To Have and Have Not. Samuelson was so impressed with the story that he decided to travel 2,000 miles to meet Hemingway and ask him for advice. “It seemed a damn fool thing to do,” Samuelson would later write, “but a twenty-two-year-old tramp during the Great Depression didn’t have to have much reason for what he did.”

And so, at the time of year when most hobos were traveling north, Samuelson headed south. He hitched his way to Florida and then hopped a freight train from the mainland to Key West. Riding on top of a boxcar, Samuelson could not see the railroad tracks underneath him–only miles and miles of water as the train left the mainland. “It was headed south over the long bridges between the keys and finally right out over the ocean,” writes Samuelson. “It couldn’t happen now–the tracks have been torn out–but it happened then, almost as in a dream.”

When Samuelson arrived in Key West he discovered that times were especially hard there. Most of the cigar factories had shut down and the fishing was poor. That night he went to sleep on the turtling dock, using his knapsack as a pillow. The ocean breeze kept the mosquitos away. A few hours later a cop woke him up and invited him to sleep in the bull pen of the city jail. “I was under arrest every night and released every morning to see if I could find my way out of town,” writes Samuelson. After his first night in the mosquito-infested jail, he went looking for the town’s most famous resident.

When I knocked on the front door of Ernest Hemingway’s house in Key West, he came out and stood squarely in front of me, squinty with annoyance, waiting for me to speak. I had nothing to say. I couldn’t recall a word of my prepared speech. He was a big man, tall, narrow-hipped, wide-shouldered, and he stood with his feet spread apart, his arms hanging at his sides. He was crouched forward slightly with his weight on his toes, in the instinctive poise of a fighter ready to hit.

“What do you want?” said Hemingway. After an awkward moment, Samuelson explained that he had bummed his way from Minneapolis just to see him. “I read your story ‘One Trip Across’ in Cosmopolitan. I liked it so much I came down to have a talk with you.” Hemingway seemed to relax. “Why the hell didn’t you say you just wanted to chew the fat? I thought you wanted to visit.” Hemingway told Samuelson he was busy, but invited him to come back at one-thirty the next afternoon.

After another night in jail, Samuelson returned to the house and found Hemingway sitting in the shade on the north porch, wearing khaki pants and bedroom slippers. He had a glass of whiskey and a copy of the New York Times. The two men began talking. Sitting there on the porch, Samuelson could sense that Hemingway was keeping him at a safe distance: “You were at his home but not in it. Almost like talking to a man out on a street.” They began by talking about the Cosmopolitan story, and Samuelson mentioned his failed attempts at writing fiction. Hemingway offered some advice.

“The most important thing I’ve learned about writing is never write too much at a time,” Hemingway said, tapping my arm with his finger. “Never pump yourself dry. Leave a little for the next day. The main thing is to know when to stop. Don’t wait till you’ve written yourself out. When you’re still going good and you come to an interesting place and you know what’s going to happen next, that’s the time to stop. Then leave it alone and don’t think about it; let your subconscious mind do the work. The next morning, when you’ve had a good sleep and you’re feeling fresh, rewrite what you wrote the day before. When you come to the interesting place and you know what is going to happen next, go on from there and stop at another high point of interest. That way, when you get through, your stuff is full of interesting places and when you write a novel you never get stuck and you make it interesting as you go along.”

Hemingway advised Samuelson to avoid contemporary writers and compete only with the dead ones whose works have stood the test of time. “When you pass them up you know you’re going good.” He asked Samuelson what writers he liked. Samuelson said he enjoyed Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. “Ever read War and Peace?” Hemingway asked. Samuelson said he had not. “That’s a damned good book. You ought to read it. We’ll go up to my workshop and I’ll make out a list you ought to read.”

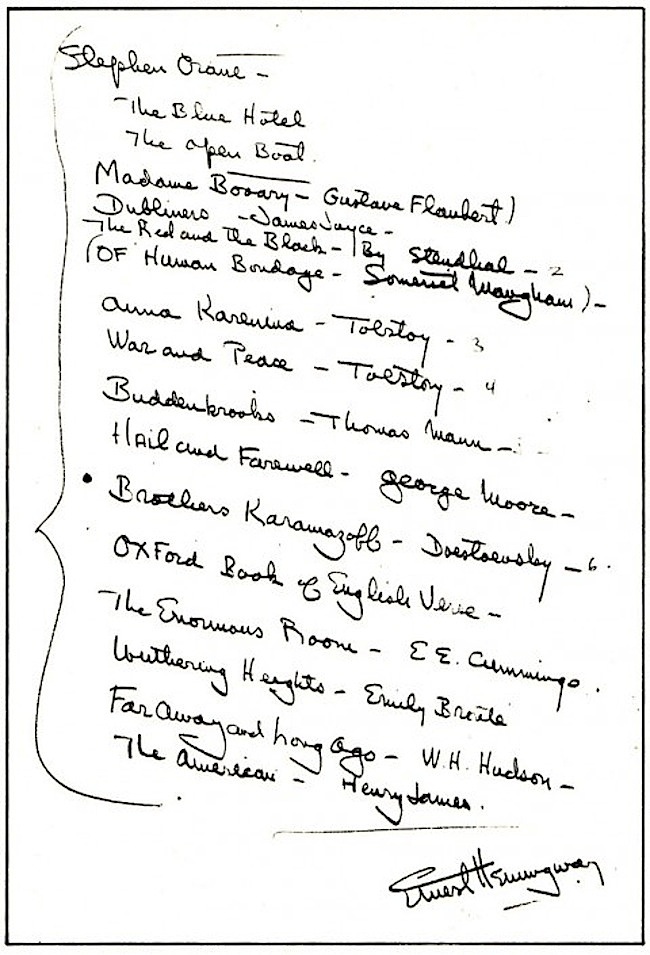

His workshop was over the garage in back of the house. I followed him up an outside stairway into his workshop, a square room with a tile floor and shuttered windows on three sides and long shelves of books below the windows to the floor. In one corner was a big antique flat-topped desk and an antique chair with a high back. E.H. took the chair in the corner and we sat facing each other across the desk. He found a pen and began writing on a piece of paper and during the silence I was very ill at ease. I realized I was taking up his time, and I wished I could entertain him with my hobo experiences but thought they would be too dull and kept my mouth shut. I was there to take everything he would give and had nothing to return.

Hemingway wrote down a list of two short stories and 14 books and handed it to Samuelson. Most of the texts you can find in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices. If the texts don’t appear in our eBook collection itself, you’ll find a link to the text directly below.

- “The Blue Hotel” by Stephen Crane

- “The Open Boat” by Stephen Crane

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

- Dubliners by James Joyce

- The Red and the Black by Stendhal

- Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

- Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann

- Hail and Farewell by George Moore

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- The Oxford Book of English Verse

- The Enormous Room by E.E. Cummings

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

- Far Away and Long Ago by W.H. Hudson

- The American by Henry James

Hemingway reached over to his shelf and picked up a collection of stories by Stephen Crane and gave it to Samuelson. He also handed him a copy of his own novel, A Farewell to Arms. “I wish you’d send it back when you get through with it,” Hemingway said of his own book. “It’s the only one I have of that edition.” Samuelson gratefully accepted the books and took them back to the jail that evening to read. “I did not feel like staying there another night,” he writes, “and the next afternoon I finished reading A Farewell to Arms, intending to catch the first freight out to Miami. At one o’clock, I brought the books back to Hemingway’s house.” When he got there he was astonished by what Hemingway said.

“There is something I want to talk to you about. Let’s sit down,” he said thoughtfully. “After you left yesterday, I was thinking I’ll need somebody to sleep on board my boat. What are you planning on now?”

“I haven’t any plans.”

“I’ve got a boat being shipped from New York. I’ll have to go up to Miami Tuesday and run her down and then I’ll have to have someone on board. There wouldn’t be much work. If you want the job, you could keep her cleaned up in the mornings and still have time for your writing.”

“That would be swell,” replied Samuelson. And so began a year-long adventure as Hemingway’s assistant. For a dollar a day, Samuelson slept aboard the 38-foot cabin cruiser Pilar and kept it in good condition. Whenever Hemingway went fishing or took the boat to Cuba, Samuelson went along. He wrote about his experiences–including those quoted and paraphrased here–in a remarkable memoir, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba. During the course of that year, Samuelson and Hemingway talked at length about writing. Hemingway published an account of their discussions in a 1934 Esquire article called “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter.” (Click here to open it as a PDF.) Hemingway’s article with his advice to Samuelson was one source for our February 19 post, “Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction.”

When the work arrangement had been settled, Hemingway drove the young man back to the jail to pick up his knapsack and violin. Samuelson remembered his feeling of triumph at returning with the famous author to get his things. “The cops at the jail seemed to think nothing of it that I should move from their mosquito chamber to the home of Ernest Hemingway. They saw his Model A roadster outside waiting for me. They saw me come out of it. They saw Ernest at the wheel waiting and they never said a word.”

Note: An earlier version of this post originally appeared on our site in May, 2013.

Related Content

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Christopher Hitchens Creates a Reading List for Eight-Year-Old Girl

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe