In 1975, the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend published his highly contrarian Against Method, a book in which he argued that “science is essentially an anarchic enterprise,” and as such, ought to be accorded no more privilege than any other way of knowing in a democratic society. Motivated by concerns about science as a domineering ideology, he argued the historical messiness of scientific practice, in which theories come about not through elegant logical thinking but often by complete accident, through copious trial and error, intuition, imagination, etc. Only in hindsight do we impose restrictions and tidy rules and narratives on revolutionary discoveries.

Several years later, in the third, 1993 edition of the book, Feyerebend observed with alarm the same widespread anti-science bias that Carl Sagan wrote of two years later in Demon-Haunted World. “Times have changed,” he wrote, “Considering some tendencies in U.S. education… and in the world at large I think that reason should now be given greater weight.”

Feyerabend died the following year, but I wonder how he might revise or qualify a 2018 edition of the book, or whether he would republish it at all. Politically-motivated science denialism reigns. Indeed, a blithe denial of any observable reality, aided by digital technology, has become a dystopian new norm. But as the philosopher also commented, such circumstances may “occur frequently today… but may disappear tomorrow.”

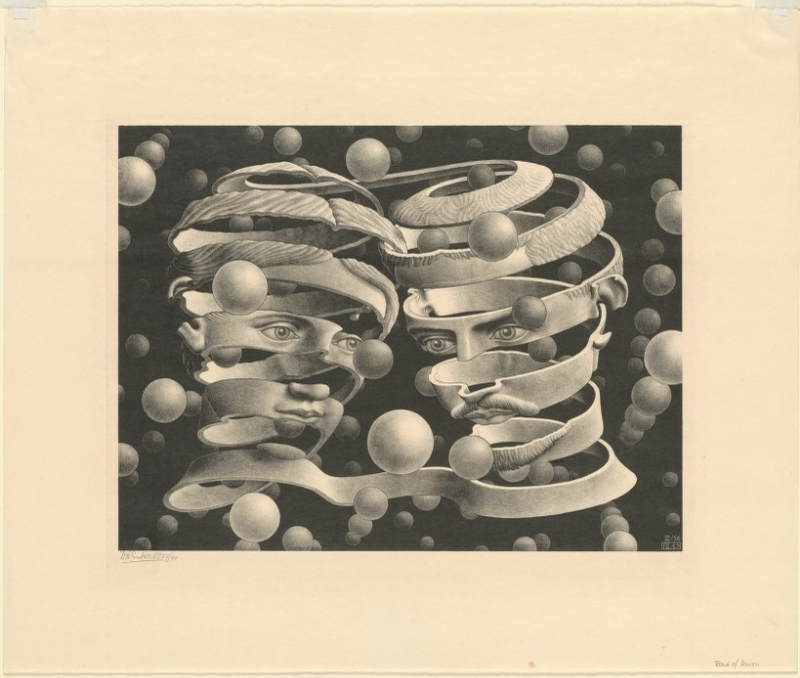

In the recorded history of human inquiry across cultures and civilizations, we see ideas we call scientific co-existing with what we recognize as pseudo- and anti-scientific notions. The differences aren’t always very clear at the time. And then, sometimes, they are. During the so-called Age of Reason, when the development of the modern sciences in Europe slowly eclipsed other modes of explanation, one obscure group of contrarians persisted in almost comically stubborn unreason. Calling themselves the Muggletonians, the Protestant sect—like those today who deny climate change and evolution—resisted an overwhelming consensus of empirical science, the Copernican view of the solar system, despite all available evidence the contrary. In so doing, they left behind a series of “beautiful celestial maps,” notes Greg Miller at National Geographic, some of which resemble William Blake’s visual poetry.

The sect began in 1651, when a London tailor named John Reeve “claimed to have received a message from God” naming his cousin Lodowicke Muggleton as the “’last messenger for a great work unto this bloody unbelieving world.’… One of the main principles of their faith, a later observer wrote, was that ‘There is no Devil but the unclean Reason of men.’” Their view of the universe, based, of course, on scripture, resembles the Medieval Catholic view that Galileo attempted to correct, but their principle antagonist was not the Italian polymath or the earlier Renaissance astronomer Copernicus, but the great scientific mind of the time, Isaac Newton, whom Muggletonians railed against into the 19th and even 20th century. Muggletonians, Miller writes,” had remarkable longevity—the last known member died in 1979 after donating the sect’s archive of books and papers… to the British Library.”

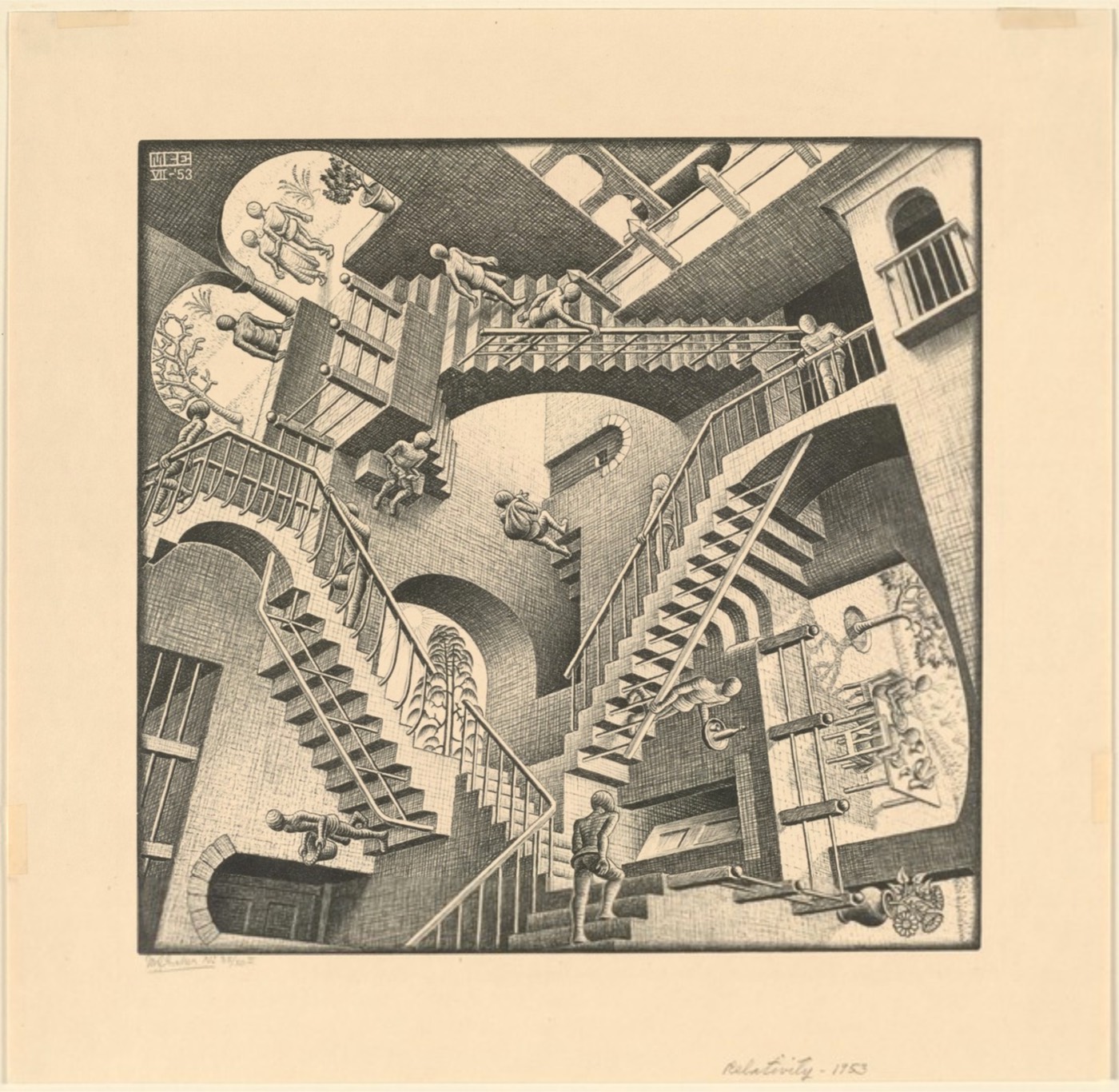

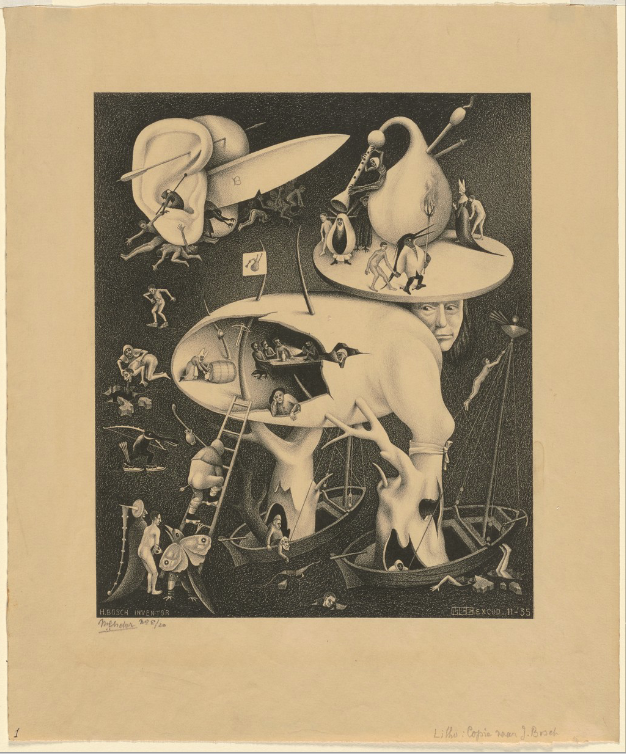

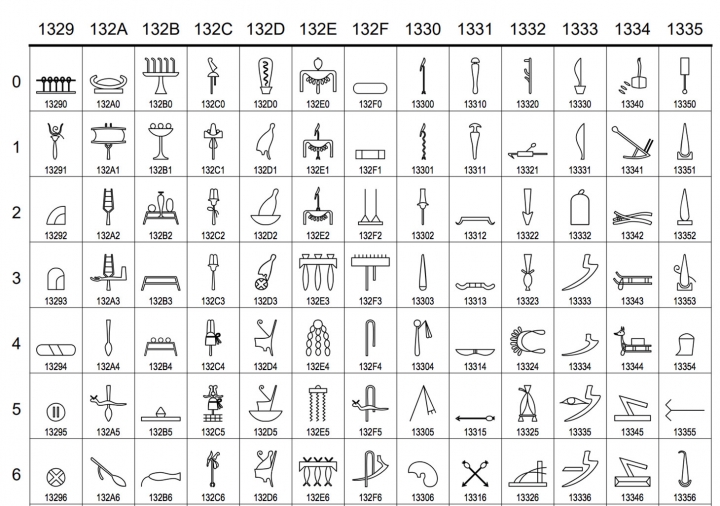

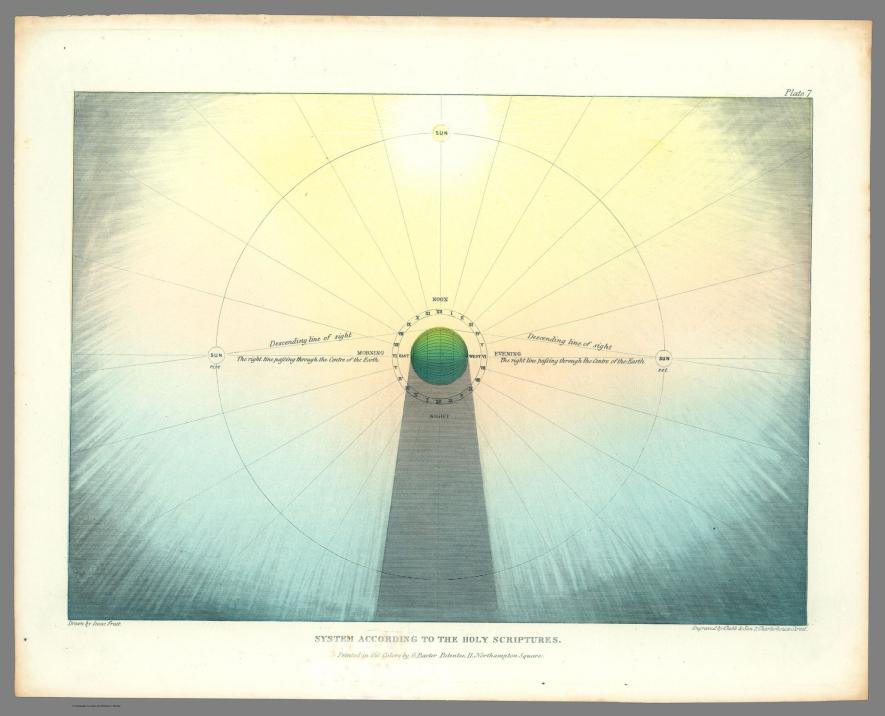

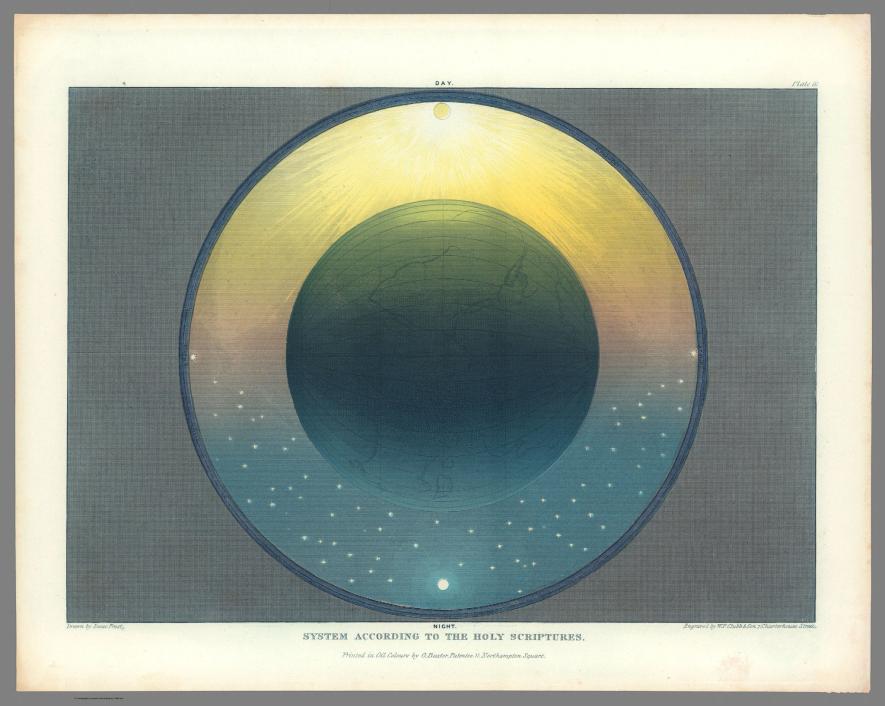

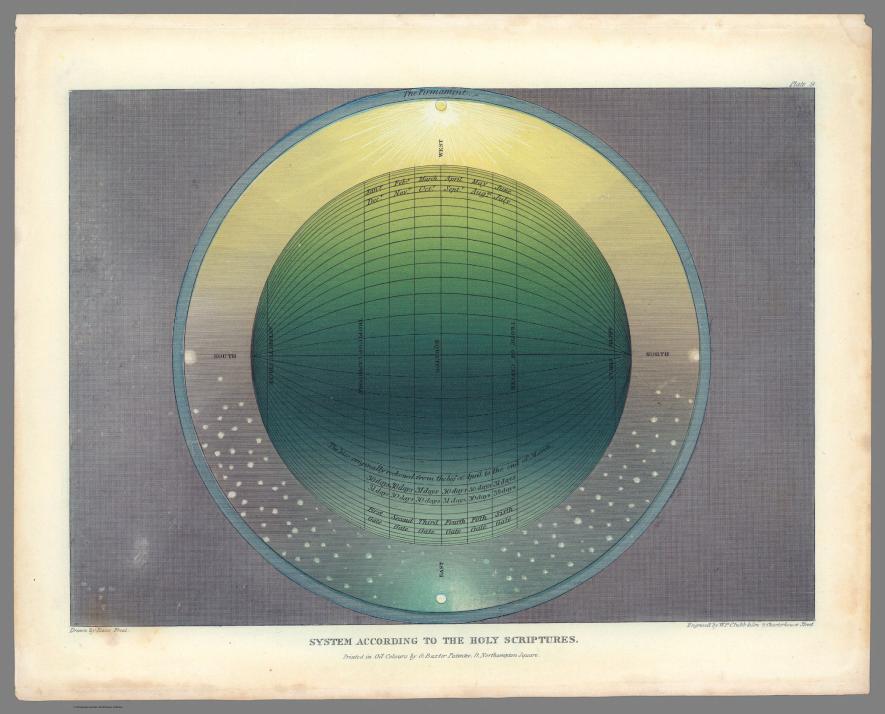

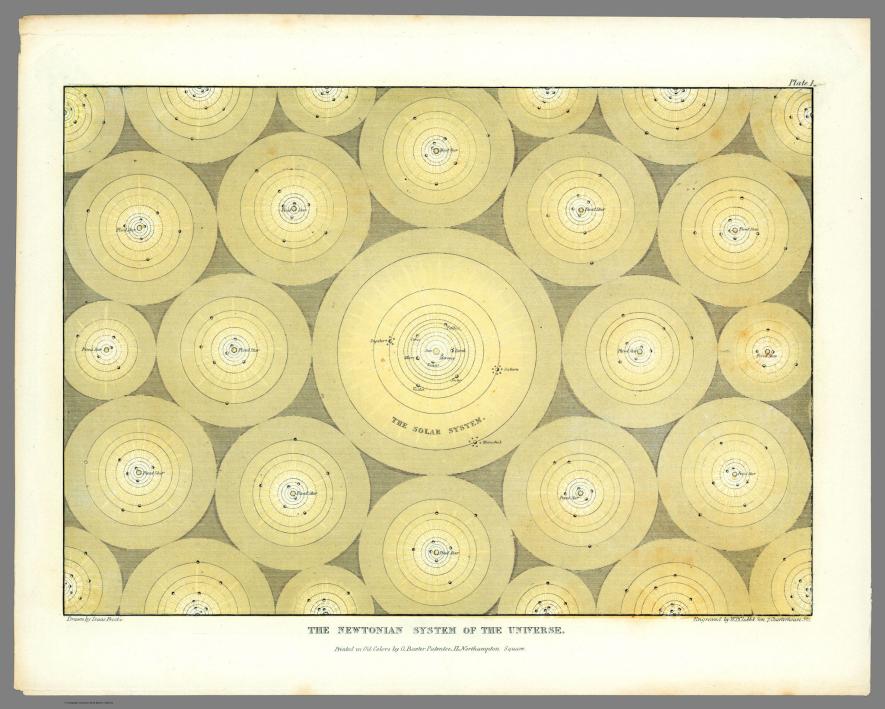

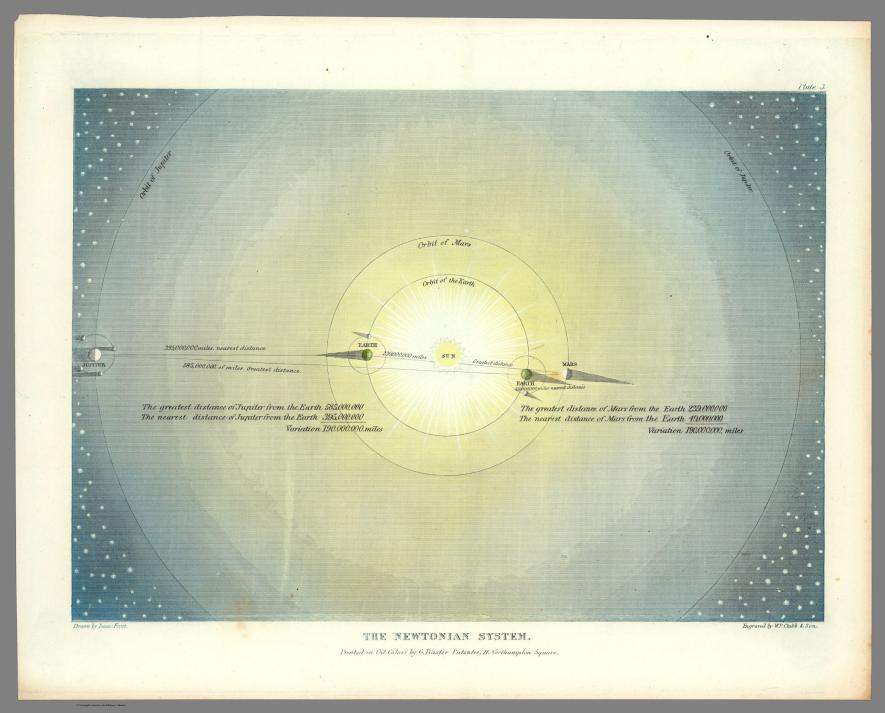

These plates come from an 1846 book called Two Systems of Astronomy. Written by Muggletonian Isaac Frost, it “pitted the scientific system of Isaac Newton—which held that the gravitational pull of the sun holds the Earth and other planets in orbit around it—against an Earth-centered universe based on a literal interpretation of the Bible.” The plate above, for example, “attempts to show the absurdity of the Newtonian system by depicting our solar system as one of many in an infinite and godless universe.” Ironically, in attempting to ridicule Newton (who was himself a pseudo-scientist and Biblical literalist in other ways), the Muggletonians stumbled upon the view of modern astronomers, who extrapolate a mind-boggling number of possible solar systems in an observable universe of over 100 billion galaxies (though these systems are not enclosed cells crammed together side-by-side). Another plate, below, shows Frost’s depiction of the hated Newtonian system, with the Earth, Mars, and Jupiter orbiting the Sun.

The other maps, further up, all represent the Muggletonian view. Historian of science Francis Reid describes it thus:

According to Frost, Scripture clearly states that the Sun, the Moon and the Stars are embedded in a firmament made of congealed water and revolve around the Earth, that Heaven has a physical reality above and beyond the stars, and that the planets and the Moon do not reflect the Sun’s rays but are themselves independent sources of light.

Frost gave lectures at “establishments set up for the education of artisans and other workmen.” It seems he didn’t attract much attention and was frequently heckled by audience members. Like flat earthers, Muggletonians were treated as cranks, and unlike today’s religious anti-science crusaders, they never had the power to influence public policy or education. For this reason, perhaps, it is easy to see them as quaintly humorous. Frost’s maps, as Miller writes, “remain strangely alluring” for both their artistic quality and their astonishingly determined credulity. The plates are now part of the massive David Rumsey collection, which houses thousands of rare historical maps. For another fascinating look at religious cartography, see Miller’s National Geographic post “mapping the Apocalypse.”

Related Content:

How a Book Thief Forged a Rare Edition of Galileo’s Scientific Work, and Almost Pulled it Off

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness