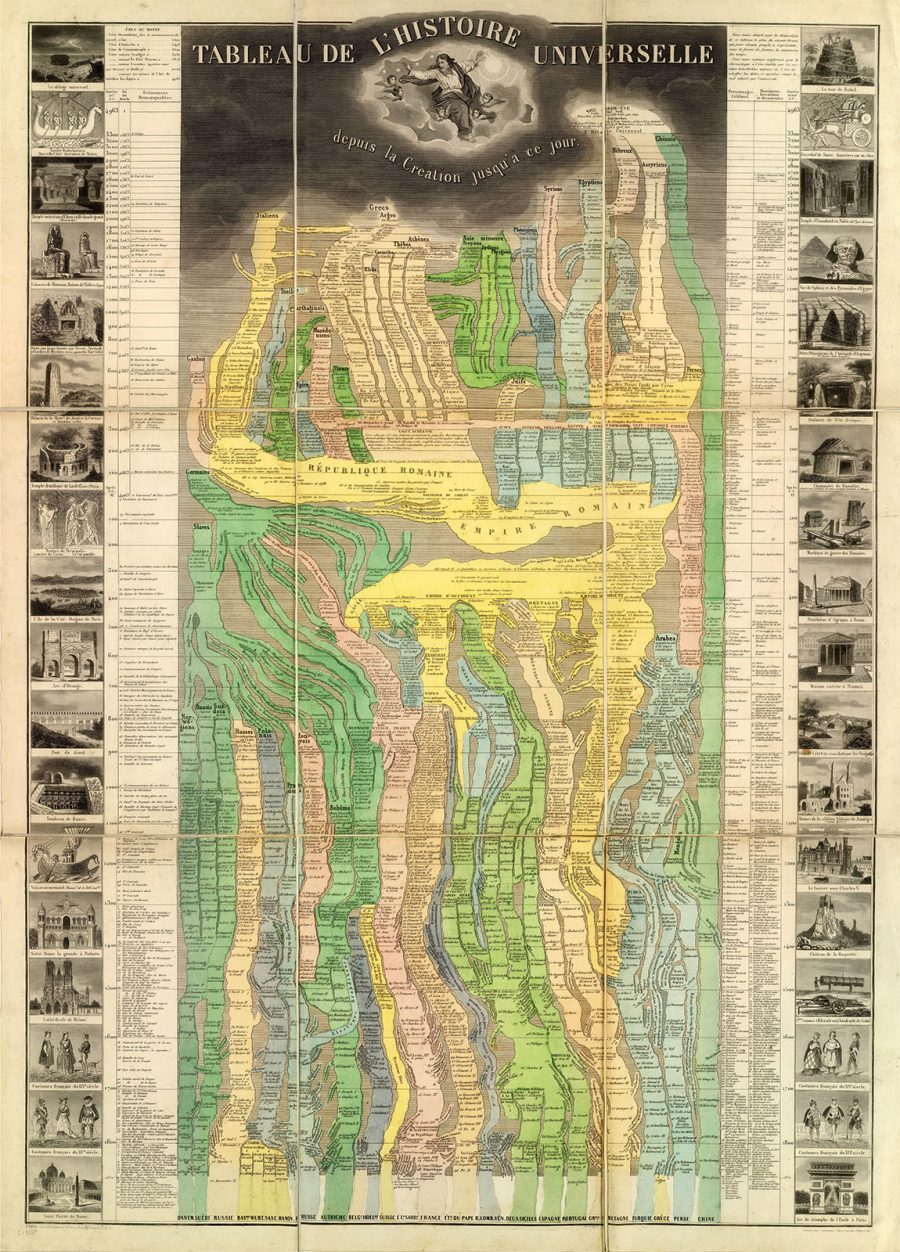

We start to understand history by listening to it told to us verbally, which lets us visualize it in our imagination. But how much more might we understand history if we could see it rendered visually right before our eyes? That question seems to have occupied the minds of certain of the cartographers of 19th-century Europe, those who wanted to take their craft beyond its traditional limits in order to do for chronology what it had long done for geography. Here we have one of the most glorious such attempts in existence, Eugene Pick’s 1858 Tableau De L’Histoire Universelle — or at least the half covering the civilizations of the Eastern Hemisphere — as held in the David Rumsey Map Collection.

At first glance, all of the information on the map might appear overwhelming. But zoom in (looking at the center first, ideally from top to bottom) and you’ll soon grasp how Pick has depicted the history of the world, as a mid-19th-century Frenchman would conceive of it it, by drawing a kind of network of rivers and tributaries.

The “sources” of ancient civilizations, like those of the Greeks, the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, and the Chinese, flow down to those of various descendants — the Gauls, the Norwegians, the Russians, the Turks — and the mighty empires in which they pool, and arrive at the nations of the Danes, the Swedes, the Belgians, the Spanish, the Persians, and others besides. In total the map covers 6,000 years of history, moving from 4004 B.C. to 1856.

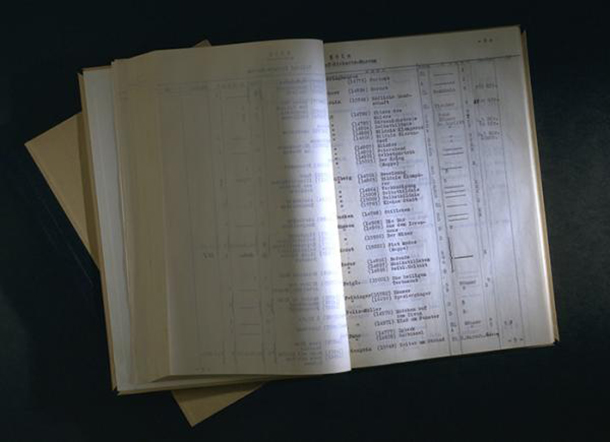

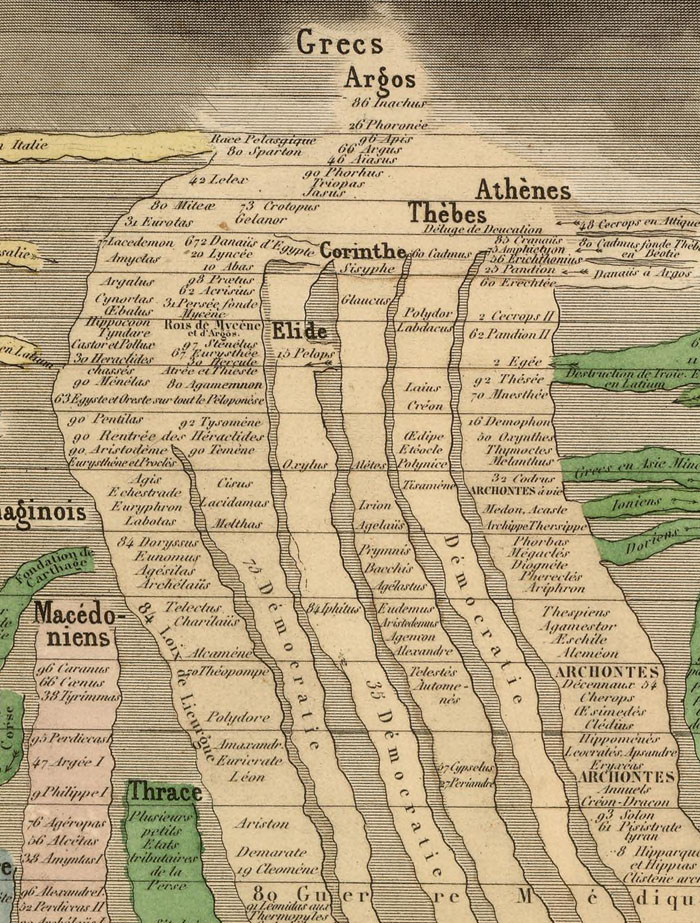

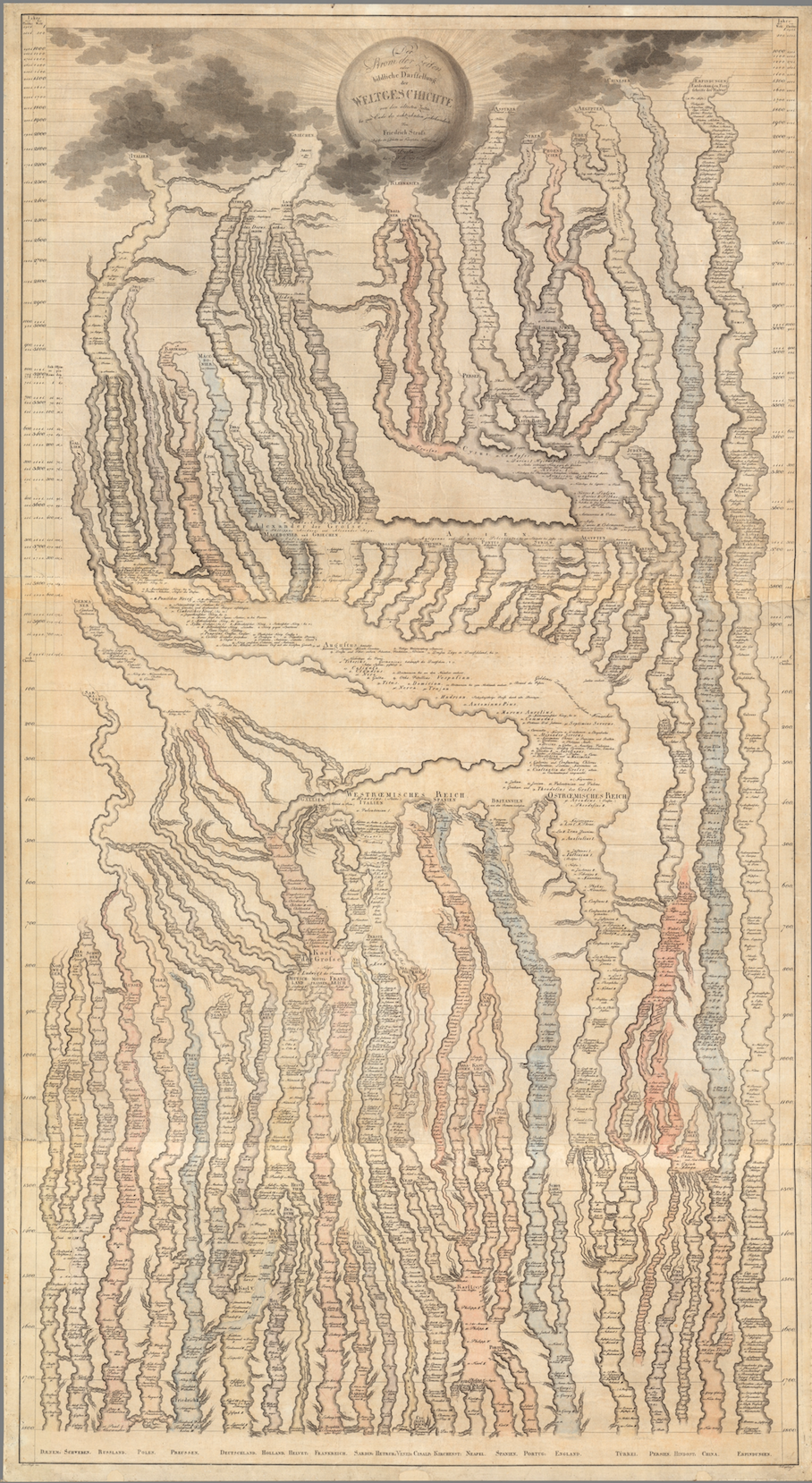

This technique of visualizing history has its precedents, including Friedrich Strass’ Der Strom der Zeiten oder bildliche Darstellung der Weltgeschichte, pictured just above (and later updated by American mapmaker Joseph Hutchins Colton as The Stream of Time in the 1840s and 1860s.) The David Rumsey Map Collection notes that, unlike Strass’ map, Pick’s also has “vignettes of people, buildings, historical scenes and important places in the history of the world” lined up on either side of the main content. It thus illuminates the abstract and continuous central rendering of history with representative, discrete ones, showing viewers everything from the Biblical flood and the Tower of Babel to the Great Sphinx of Giza and Agrippa’s Pantheon to Notre Dame and the Arc de Triomphe. It has a certain francocentrism, to be sure, but consider how many in Pick’s time considered France the center of humanity’s genius. Producing a map as compelling as this one couldn’t have diminished that image.

Related Content:

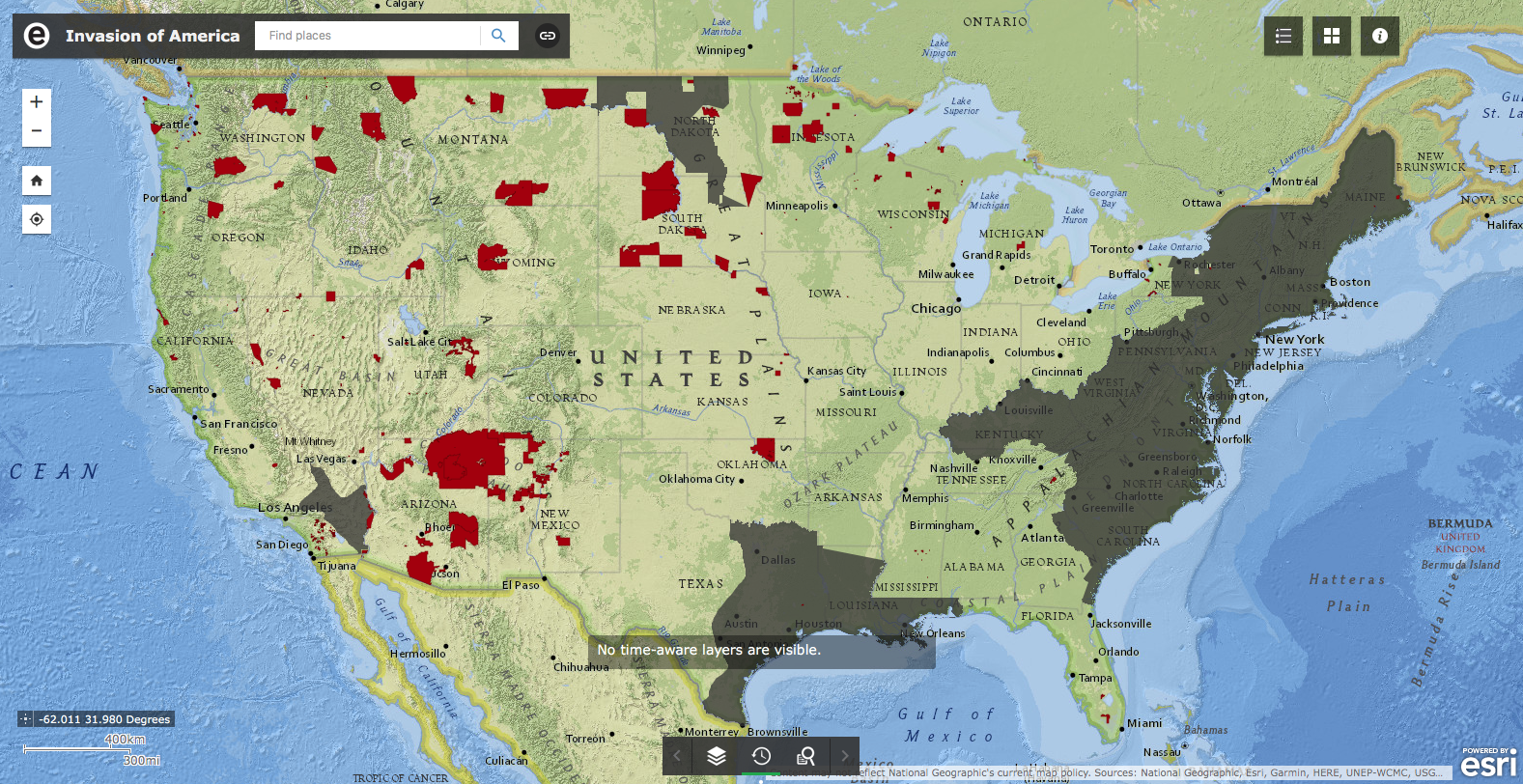

Watch the History of the World Unfold on an Animated Map: From 200,000 BCE to Today

The History of Civilization Mapped in 13 Minutes: 5000 BC to 2014 AD

5‑Minute Animation Maps 2,600 Years of Western Cultural History

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.