Most of us got hooked up to the internet in the 1990s or thereabouts, though the true early adopters did it when personal computers first blew up in the 1980s. But certain Canadian households got online even earlier, in the late 1970s, although not quite on the internet as we know it: they had Telidon, a phone line-connected videotex/teletex system that used a regular television as a display. “It is no exaggeration to say that the telecommunications marketplace in Canada was gripped by Telidon fever from late 1979 to late 1982,” writes Donald Gilles in the Canadian Journal of Communications. Fueling that fever was “hope and belief in technology – science-based technology – as an agent of change, a bringer of novelty, and enhancer of life.”

When it first came available, Telidon’s content providers included “corporations and interests such as The Bay, Encyclopedia Britannica and the Toronto Star,” writes the CBC’s Chris Hampton, but “a community of arts-minded electronics wonks, telecom prophets and other curious sorts coalesced around it, embracing it as an art medium.”

You can see some of those Telidon creators interviewed in the short Motherboard documentary at the top of the post. While businesses experimented with possibilities of banking and shopping through the system, artists pushed its boundaries even further, using its now severe-seeming technological limitations as a catalyst for visual creativity. On some months, artist Bill Perry’s Telidon magazine Computerese drew more viewers than every other provider combined.

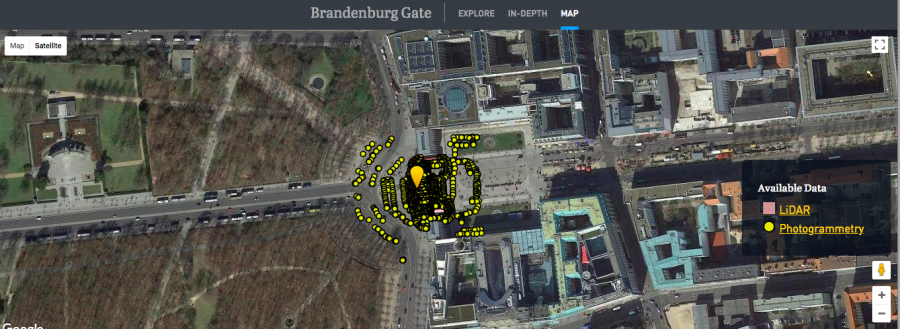

Now, more than 30 years after its discontinuation, Telidon has attracted attention again. It turns out that its early-computer-art aesthetic has aged quite well, as seen in the examples now being pulled from the archives and Instagrammed by Toronto new-media center InterAccess. Originally founded to make Telidon development tools available to the artist community, InterAccess launched this social media project as a way of celebrating its own 35th birthday. Looking back on all the uses artists found for Telidon — everything from abstract quasi-animations to a study of perspectives on the Cold War — we can imagine how comparatively boundless the modern internet would have seemed to them. But we might also wonder what that modern internet would look like if it had a little more of their artistically and technologically adventurous spirit.

Related Content:

The Internet Imagined in 1969

From the Annals of Optimism: The Newspaper Industry in 1981 Imagines its Digital Future

What the Entire Internet Looked Like in 1973: An Old Map Gets Found in a Pile of Research Papers

Andy Warhol’s Lost Computer Art Found on 30-Year-Old Floppy Disks

Watch Brian Eno’s “Video Paintings,” Where 1980s TV Technology Meets Visual Art

The Story of Habitat, the Very First Large-Scale Online Role-Playing Game (1986)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.