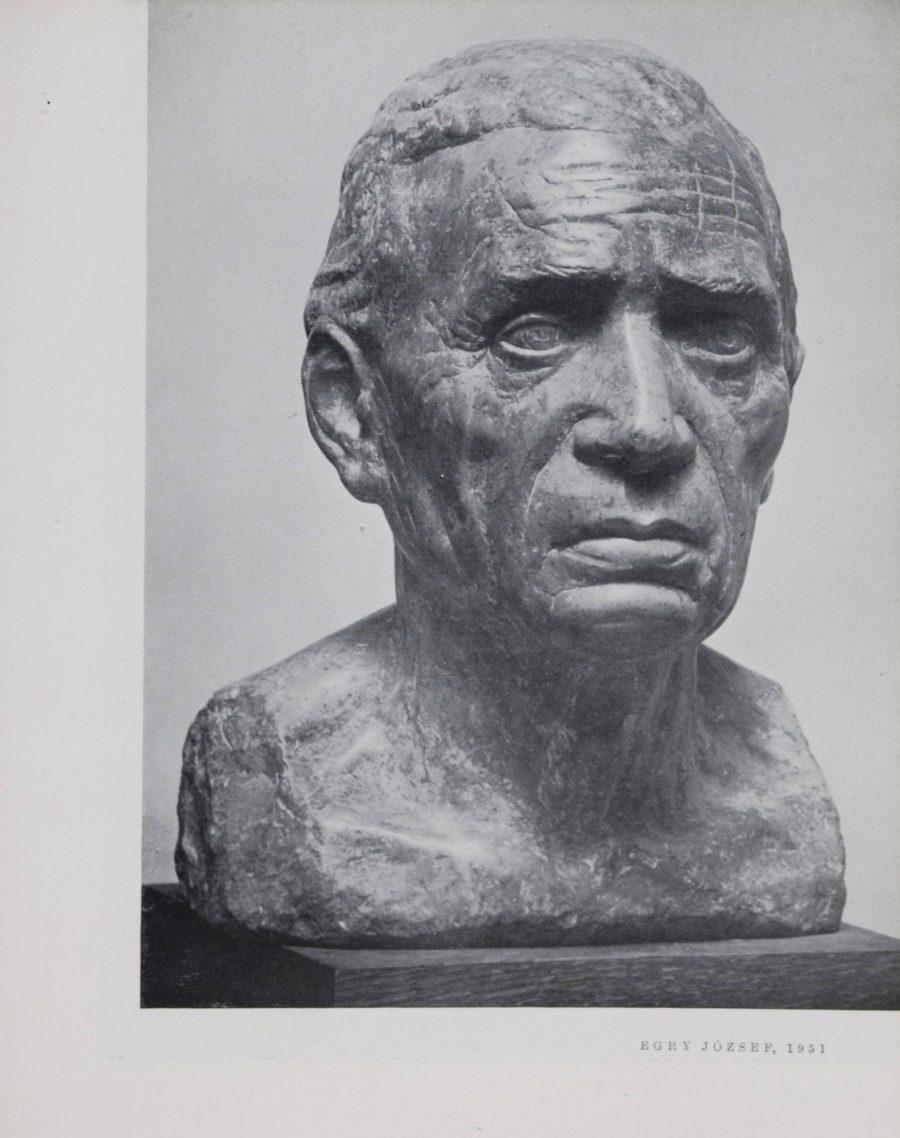

Image by Christiaan Tonnis, via Wikimedia Commons

William S. Burroughs was a cultural prism. Through him, the mid-century demi-monde of illicit drug use and marginalized sexualities—of occult beliefs, alternative religions, and bizarre conspiracy theories—was refracted on the page in experimental writing that inspired everyone from his fellow Beats to the punks of later decades to name-your-countercultural-touchstone of the past fifty years or so. There are many such people in history: those who go to the places that most fear to tread and send back reports written in language that alters reality. To quote L. Ron Hubbard, another writer who purported to do just that, “the world needs their William Burroughses.”

And Burroughs, so it appears, needed L. Ron Hubbard, at least for most of the sixties, when the writer became a devout follower of the Church of Scientology. The sci-fi-inspired “new religious movement” that needs no further introduction proved irresistible in 1959 when Burroughs met John and Mary Cooke, two founding members of the church who had been trying to recruit Burroughs’ friend and frequent artistic partner Brion Gysin. “Ultimately,” writes Lee Konstantinou at io9, “it was Burroughs, not Gysin, who explored the Church that L. Ron Hubbard built. Burroughs took Scientology so seriously that he became a ‘Clear’ and almost became an ‘Operating Thetan.’ ”

Burroughs immersed himself without reservation in the practices and principles of Scientology, writing letters to Allen Ginsberg that same year in which he recommends his friend “contact [a] local chapter and find an auditor. They do the job without hypnosis or drugs, simply run the tape back and forth until the trauma is wiped off. It works. I have used the method—partially responsible for recent changes.” No doubt Burroughs had his share of personal trauma to overcome, but he also found Scientology especially conducive to his greater creative project of countering “the Reactive Mind… an ancient instrument of control designed to stultify and limit the potential for action in a constructive or destructive direction.”

The method of “auditing” gave Burroughs a good deal of material to work with in his fiction and filmmaking experiments. He and Gysin included Scientology’s language in a short 1961 film called “Towers Open Fire,” which was, writes Konstantinou, “designed to show the process of control systems breaking down.” Scientology appeared in 1962’s The Ticket That Exploded and again in 1964’s Nova Express. Each novel references the concept of “engrams,” which Burroughs succinctly defines as “traumatic material.” During this hugely productive period, the radically anti-authoritarian Burroughs “associated the group with a range of mind-expanding and mind-freeing practices.”

It’s easy to say Burroughs uncritically partook of a certain sugary beverage. But he clearly made his own idiosyncratic uses of Scientology, incorporating it within the syncretic constellation of references, practices, and cut-up techniques “designed to jam up what he called ‘the Reality Studio,’ aka the everyday, conditioned, mind-controlled reality.” An inevitable turning point came, however, in 1968, as Burroughs journeyed deeper into Scientology’s secret order at the world headquarters in Saint Hill Manor in the UK. There, he reported, he “had to work hard to suppress or rationalize his persistently negative feelings toward L. Ron Hubbard during auditing sessions.”

Burroughs’ dislike of the church’s founder and extreme aversion to “what he considered its Orwellian security protocols” eventuated his break with Scientology, which he undertook gradually and publicly in a series of “bulletins” published during the late sixties in the London magazine Mayfair. Before his “clearing course” with Hubbard, in a 1967 article excerpted and republished as a pamphlet by the church itself, Burroughs praises Scientology and its founder, and claims that “there is nothing secret about Scientology, no talk of initiates, secret doctrines, or hidden knowledge.”

By 1970, he had made an about-face, in a fiercely polemical essay titled “I, William Burroughs, Challenge You, L. Ron Hubbard,” published in the Los Angeles Free Press. While he continues to value some of the benefits of auditing, Burroughs declares the church’s founder “grandiose” and “fascist” and lays out his objections to its initiations, secret doctrines, and hidden knowledge, among other things:

…One does not simply pay the tuitions, obtain the materials and study. Oh no. One must JOIN. One must ‘sign up for the duration of the universe’ (Sea Org members are required to sign a billion-year contract)…. Furthermore whole categories of people are automatically excluded from training and processing and may never see Mr Hubbard’s confidential materials.

Burroughs challenges Hubbard to “show his confidential materials to the astronauts of inner space,” including Gysin, Ginsberg, and Timothy Leary; to the “students of language like Marshall MacLuhan and Noam Chompsky” [sic]; and to “those who have fought for freedom in the streets: Eldridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael, Abe Hoffman, Dick Gregory…. If he has what he says he has, the results should be cataclysmic.”

The debate continued in the pages of Mayfair when Hubbard published a lengthy and blandly genial reply to Burroughs’ challenge, in an article that also contained, in an inset, a brief rebuttal from Burroughs. The debate will surely be of interest to students of the strange history of Scientology, and it should most certainly be followed by lovers of Burroughs’ work. In the process of embracing, then rejecting, the controlling movement, he compellingly articulates a need for “unimaginable extensions of awareness” to deal with the trauma of living on what he calls the “sinking ship” of planet Earth.

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs Tells the Story of How He Started Writing with the Cut-Up Technique

When William S. Burroughs Appeared on Saturday Night Live: His First TV Appearance (1981)

Hear a Great Radio Documentary on William S. Burroughs Narrated by Iggy Pop

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness