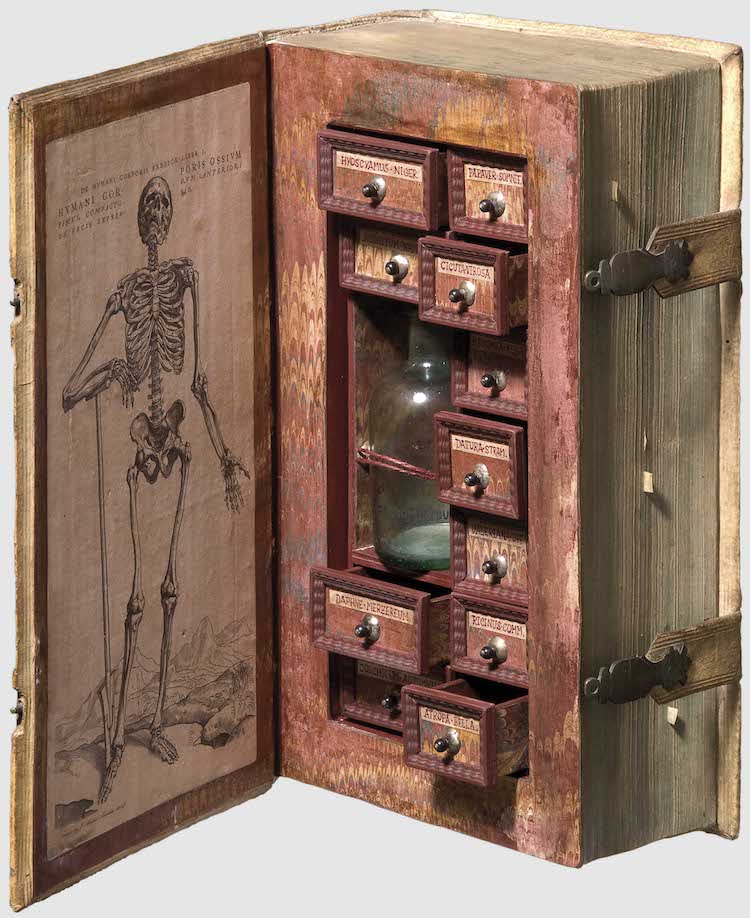

Hasn’t every child dreamed of a having a hollowed-out book on their shelf, inside of which they can hide whatever forbidden objects of mischief they like without fear of discovery? The idea surely goes back many generations, and possibly even to the era when not many adults, let along children, owned any books at all. A decade ago, a hollowed-out book dated 1682 went up on the auction block at German house Hermann Historica, and these photos of its elaborate design have captivated the imaginations of even we 21st-century beholders. But what are all the spaces within meant to contain?

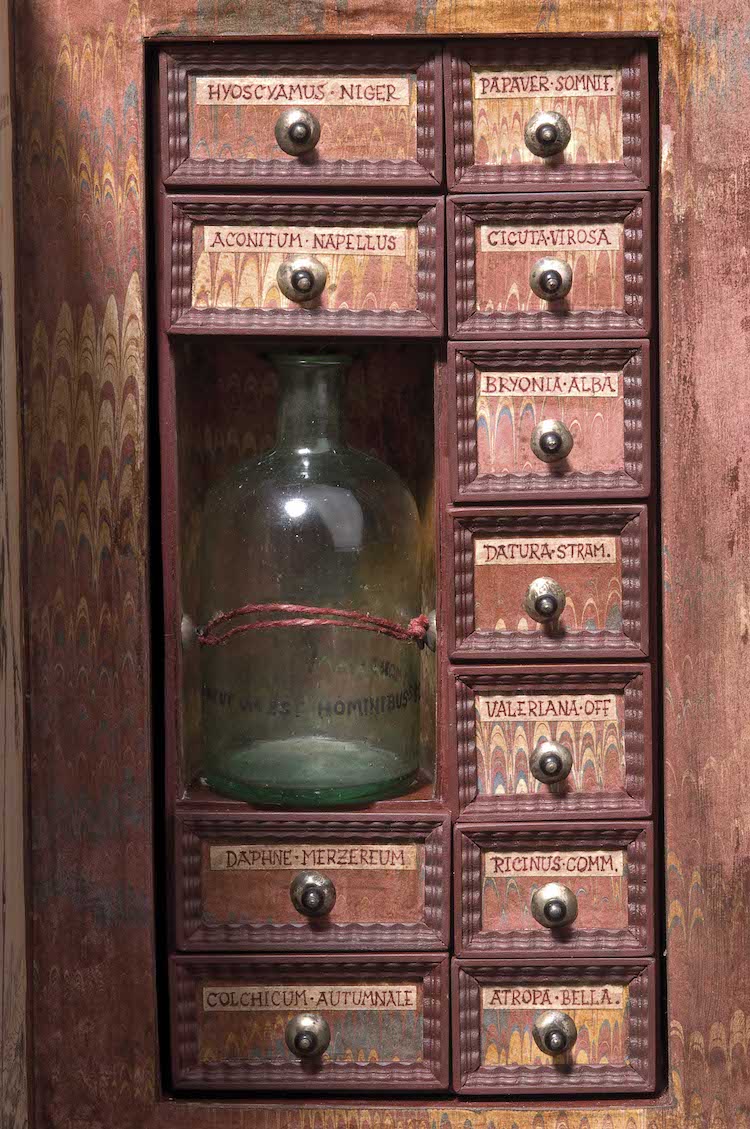

Herrman Historica’s listing describes the item as “a hollow book used as secret poison cabinet,” a conclusion presumably arrived at after examining its drawers’ “handwritten paper labels with the Latin names of different poisonous plants (among them castor-oil plant, thorn apple, deadly nightshade, valerian, etc.).” My Modern Met’s Jessica Stewart adds that “calling it an assassin’s cabinet may be a bit exaggerated,” noting that “many of these plants, while poisonous, were also part of herbal remedies —making it equally possible we are looking at an ornate medicine cabinet.”

Book Addiction breaks down the nature and uses of the plants meant to be stored in the drawers, including Hyoscyamus Niger, which in medieval times “was often used in combination with other plants to a make ‘magic brews’ with psychoactive properties”; Aconitum Napellus, which in ancient Roman times “was a such a common poison of choice among murders and assassins that its cultivation was prohibited”; and Cicuta Virosa, which some have speculated “was the hemlock used by the ancient Greek Republic as the state poison but as it is a native of northern Europe this may not be true,” but “is so toxic that a single bite into its root can be fatal” regardless.

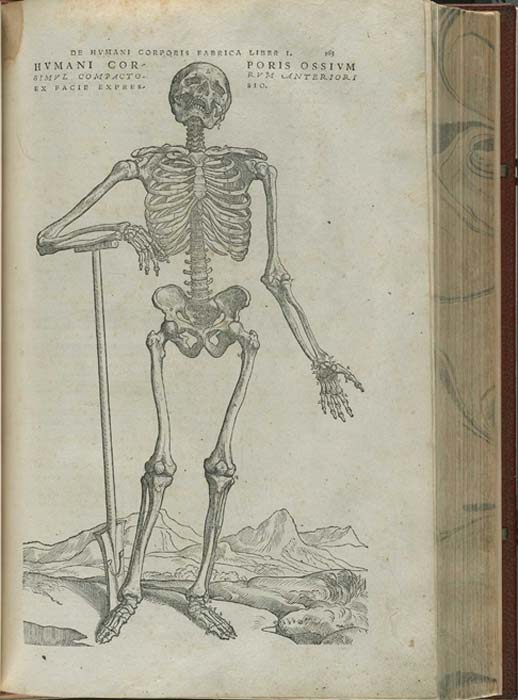

Strong stuff, whether for killing or curing. The ambiguity between those two purposes has surely stoked our modern interest in this secretly repurposed book, as has its nature as what Herrman Historica calls an “elaborately worked Kunstkammer object” — a “cabinet of curiosities” of the kind that has long fascinated mankind — “with strong reference to the memento mori theme.” That reference comes chiefly in the form of not just the proud-looking skeleton on the inside cover, but the label on the bottle provided its own compartment in the book: “Statutum est hominibus semel mori,” or “It is a fact that man must die one day.” But did the owner of this book and the tools hidden within want to hasten that day, or delay it?

Related Content:

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes

Old Books Bound in Human Skin Found in Harvard Libraries (and Elsewhere in Boston)

Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.