“A high school teacher finds out that he has terminal cancer and decides to cook meth in order to make money for his family.” Twenty years ago that would have sounded like an insane premise for a television show. Ten years ago that show actually premiered. Almost five years ago it ended its both widely watched and critically acclaimed five-season run. Breaking Bad could only have emerged at a certain point in television history, when the high-quality, cinematic drama became a viable prospect even for a basic-cable network like AMC. But it never would have got anywhere without an impressive pilot, the first episode of a series that provides a sense of what the whole thing will be like.

A pilot, for its part, can never get anywhere without an impressive screenplay. Here, YouTube video essay channel Lessons from the Screenplay breaks down the reasons the screenplay for Breaking Bad’s pilot works so well, not least because it perfectly executes the conventions of the form. First, it grabs the viewer’s attention with the image of a man barreling through the desert in a Winnebago, wearing only a underpants and a gas mask. This opening sequence, the “teaser,” quickly intensifies and ends with a feeling of life-and-death stakes. Then, when the episode properly begins, it introduces the man in the Winnebago, a chemistry teacher named Walt, by taking us through an earlier day in his highly unsatisfactory life: disrespectful students, financial woes, a passionless marriage.

Soon the screenplay addresses the implicit question, “What is missing in Walt’s life?” The scenes the pilot shows us illustrate that “he is someone who longs for control and purpose, but lacks both.” Then it delivers the “inciting incident for the show”: his collapse on the job and subsequent cancer diagnosis. Such an incident conventionally turns the protagonist’s life upside down, as this one turns Walt’s life upside down, and motivate that protagonist to take some kind of action, as it motivates Walt to team up with a former student to start a meth-cooking operation. Shortly after that, the now fearless Walt gets his first taste of power in a fight at a clothing store, beginning his transformation from the meek, put-upon Walt into the steely drug kingpin Walter White — a transformation that transfixed Breaking Bad’s audience.

“Television is historically good at keeping its characters in a self-imposed stasis so that shows go on for years or even decades,” says creator Vince Gilligan. “When I realized this, the logical next step was to think, how can I do a show in which the fundamental drive is toward change?” In this way, Breaking Bad furthered the revolution in cinematic television not just with its look and feel or even its content, but with its commitment to the idea that a character must come out of the story as a different person than he was when he entered it. The pilot manages to do in its own self-contained story while also establishing expectations for the rest of the series. Breaking Bad, most critics will agree, met those expectations and then some, but without a pilot as well-written as this, it almost certainly wouldn’t have had the chance to try.

Related Content:

Watch the Original Audition Tapes for Breaking Bad Before the Final Season Debuts

The Breaking Bad Theme Played with Meth Lab Equipment

The Science of Breaking Bad: Professor Donna Nelson Explains How the Show Gets it Right

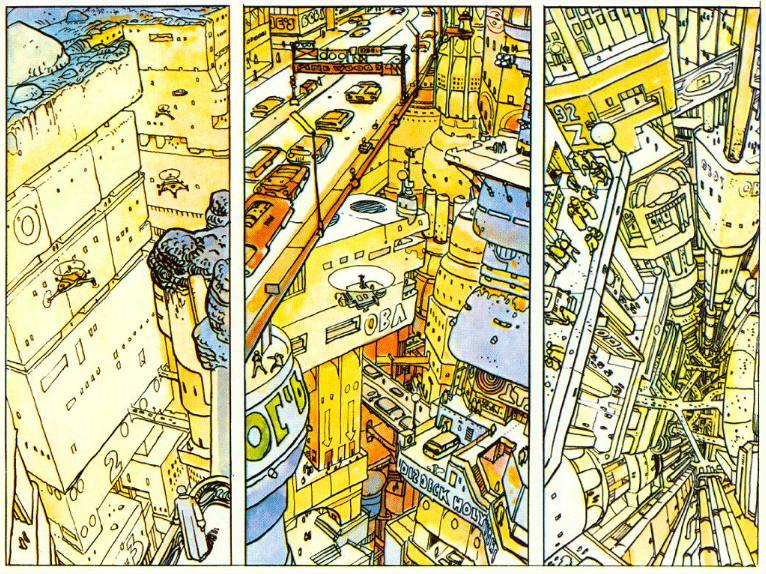

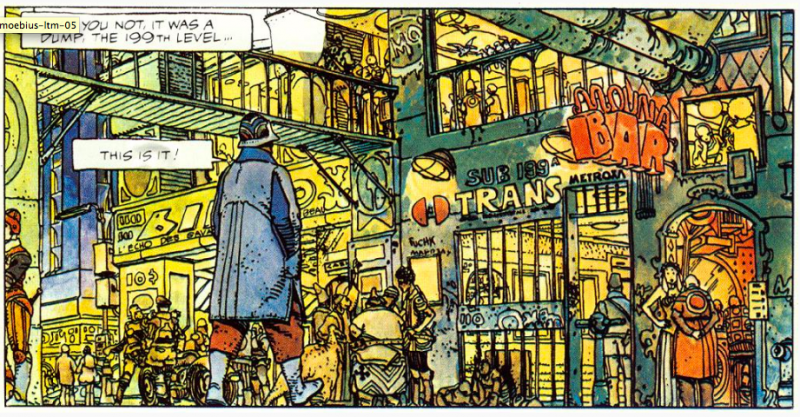

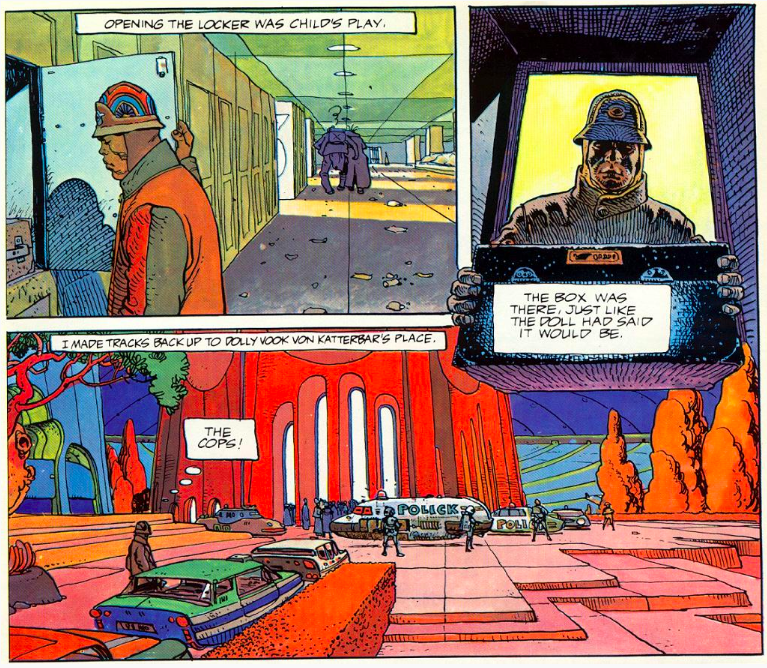

Breaking Bad Illustrated by Gonzo Artist Ralph Steadman

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.