As an English major undergrad in the 90s, I had a keen side interest in reading philosophy of all kinds. But I had little sense of what I should be reading. I browsed the library shelves, picking out what caught my attention. Not a bad way to make unusual discoveries, but if you want to get a focused, not to mention current, view of a particular field, you need to have a knowledgeable guide.

Back in those days, the internet was, as they say, in its infancy. How much better I would have fared if something like Five Books had existed! The site’s general idea, as it trumpets on its homepage, is to recommend “the best books on everything.” Argue amongst yourselves about whether any one resource can deliver on that promise, but let’s keep our focus on the excellent space of their Philosophy section, curated by freelance philosopher-at-large Nigel Warburton.

You may know Dr. Warburton from his many forays in public philosophy. Whether it’s the Philosophy Bites podcast, or its spin-offs Free Speech Bites and Ethics Bites, or his work on the BBC’s animated history of ideas series, or any one of his books, he has a rare knack for bringing the obscure and often difficult concepts of academic philosophy to light with both conversational good humor and intellectual rigor. Most of that work takes place in dialogue, the original form of classical philosophy.

The Five Books forum is no exception. In the latest post, Warburton interviews University of Sheffield’s Keith Frankish on the five best books on Philosophy of Mind. What is “Philosophy of Mind”? Read Frankish’s answer to that question here. What are his five picks? See below:

- A Materialist Theory of the Mind, by D.M. Armstrong

- Consciousness Explained, by Daniel C. Dennett

- Varieties of Meaning: The 2002 Jean Nicod Lectures, by Ruth Garrett Milikan

- The Architecture of the Mind, by Peter Carruthers

- Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension, by Andy Clark

What about the best books on Ethics for Artificial Intelligence? It’s a far more pressing question than it was when Arthur C. Clarke published 2001: A Space Odyssey, which happens to be one of the books on Oxford academic Paula Boddington’s list. In his interview with Boddington, Warburton asks for, and receives, a clarification of the phrase “ethics for artificial intelligence.” In her choice of books, Boddington recommends those below. You may not find some of them shelved in philosophy sections, but when it comes to our sci-fi present, it seems, we may need to expand our categories of thought.

- Heartificial Intelligence: Embracing Our Humanity to Maximize Machines, by John Havens

- The Technological Singularity, by Murray Shanahan

- Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy, by Cathy O’Neil

- Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right from Wrong, by Wendell Wallach and Colin Allen

- 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Arthur C. Clarke

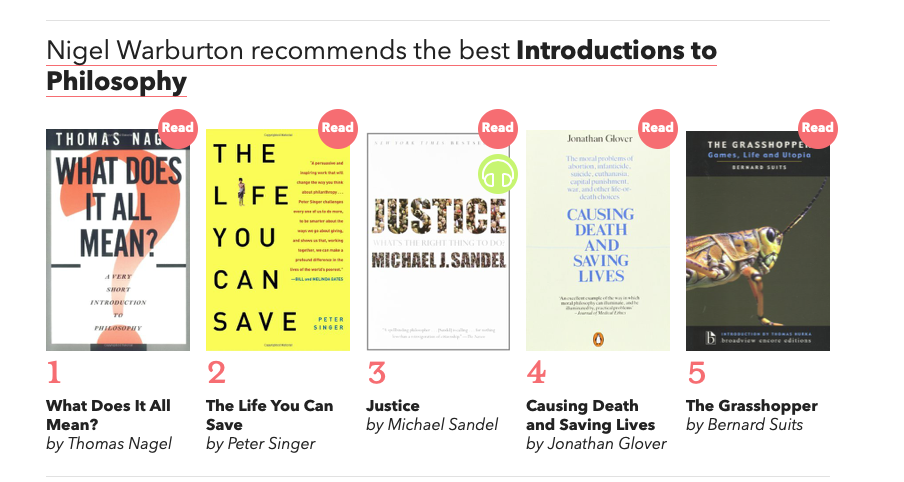

There are dozens more enlightening interviews and lists of five best books—on Nietzsche, Marx, and Hegel, on Existentialism, Stoicism, Consciousness, Chinese Philosophy…. Too many to directly quote here. There are lists from Warburton himself, on the best philosophy books from 2017, and best introductions to philosophy. The whole experience is a little like visiting, virtually, a couple dozen or so highly-regarded philosophers in every field, listening in on an informative chat, and getting a booklist from every one. You’ve still got to find and buy the books yourself (and read and talk about them), but this kind of guidance from living philosophers currently working in the field has never before been so widely and freely available outside of academia.

Related Content:

170+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

28 Important Philosophers List the Books That Influenced Them Most During Their College Days

48 Animated Videos Explain the History of Ideas: From Aristotle to Sartre

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness