When we first checked in with artist and screenwriter Todd Alcott, he was immortalizing the work of stars who hit their stride in the 70s and 80s, as highly convincing pulp novel and magazine covers inspired by their most famous songs and lyrics. David Bowie’s “Young Americans” yields an East of Eden-like blonde couple reclining in the grass. Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime” becomes an erotically violent, or violently erotic, magazine that ain’t fooling around.

Next, we took a look at Alcott’s series of pulp covers drawn from the work of Mr. Bob Dylan, bona fide godfather of classic rock, a period that gets a lion’s share of covers in Alcott’s imaginative Etsy rack, alongside other new wave and punk bands like The Clash, The Smiths, and Joy Division. Looking at these devoted tributes to musical giants of yore, rendered in adoring tributes to an even earlier era’s aesthetic, produces the kind of “of course!” reaction that makes Alcott’s work so enjoyable.

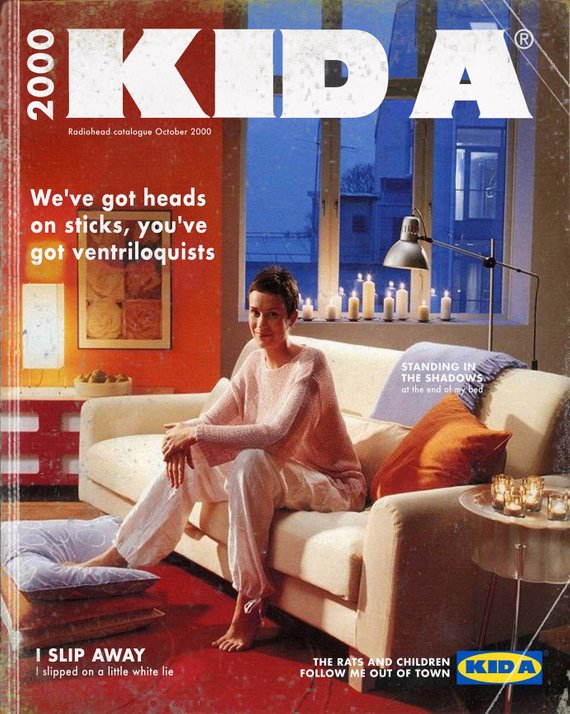

After all, pulp magazines and books are perhaps as responsible for the counterculture as LSD, with their proudly sexy poses, overheated teen fantasies, and bondage gear. (Prince gets his own series, a true joy.) But Alcott has moved on to a crop of artists who first appeared in the 90s class of alternative bands—from PJ Harvey, to Fiona Apple, to Nirvana, to Neutral Milk Hotel, to, as you can see here, Radiohead, the most long-lived and innovative stars of the era.

How well does Alcott’s approach work with artists who hit the scene when pulp fiction turned into Pulp Fiction, appropriated in a winking, expletive-filled splatter-fest that didn’t, technically, require its audience to know anything about pulp fiction? You’ll notice that Alcott has taken a novel approach to the concept in many cases (reimagining PJ Harvey’s “This is Love!” as a 50s grindhouse flick, another genre that has been heavily Tarantino-ized).

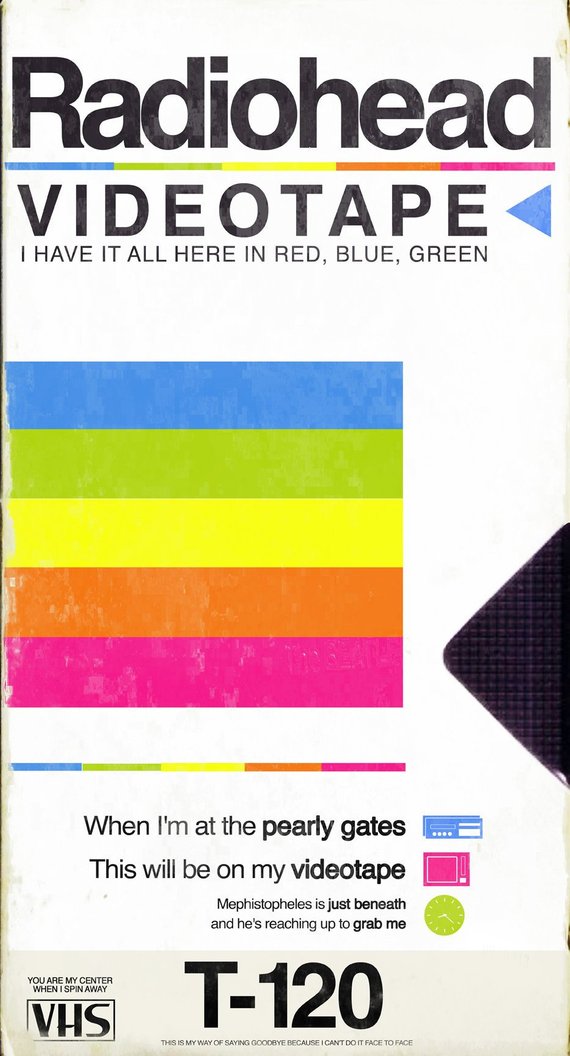

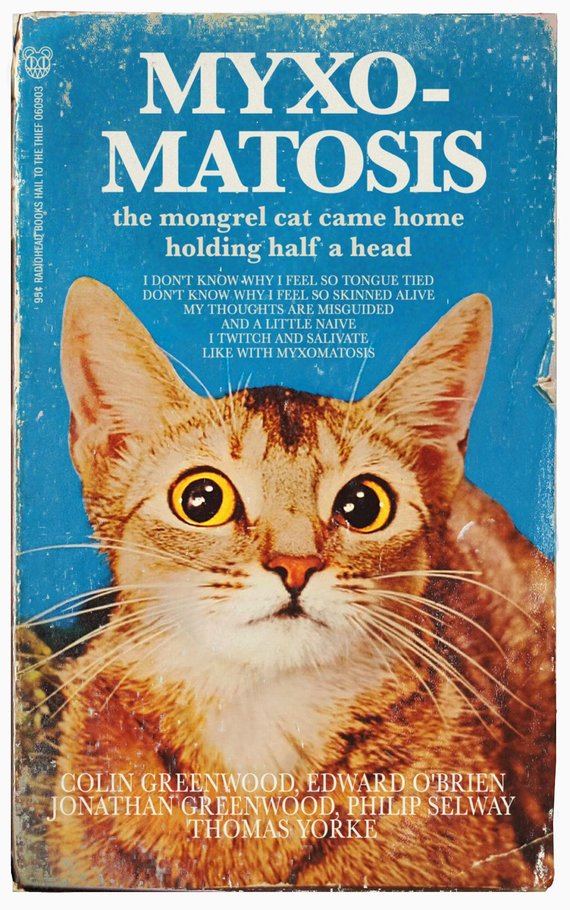

He converts Radiohead’s “Kid A” into that most treasured publication for futon-surfing hipsters circa 2000, the IKEA catalog. “Videotape” manifests in literal fashion as one of the oughties’ many objects of consumer electronics nostalgia, the 120-minute VHS. And “Myxomatosis,” from 2003’s Hail to the Thief, appears as a 1970s cat book, an artifact many Radiohead fans at the turn of the millennium might treasure as both an ironic Tumblr goof and a poignant reminder of childhood.

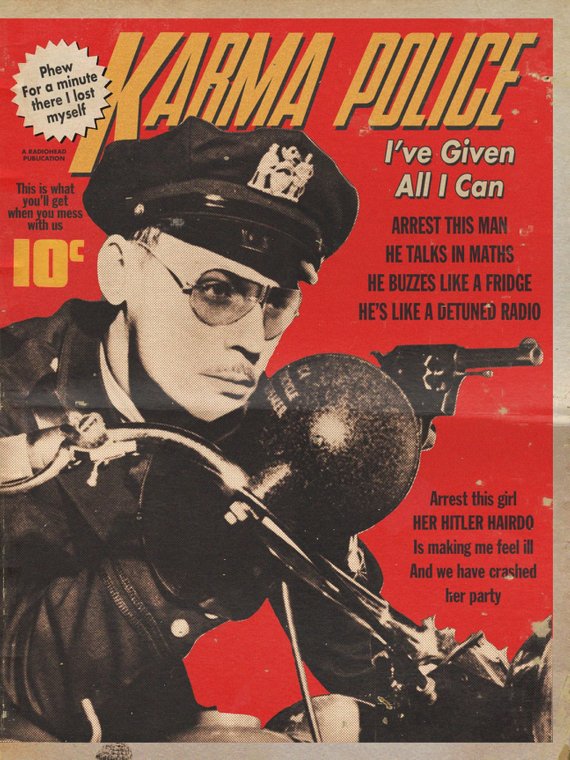

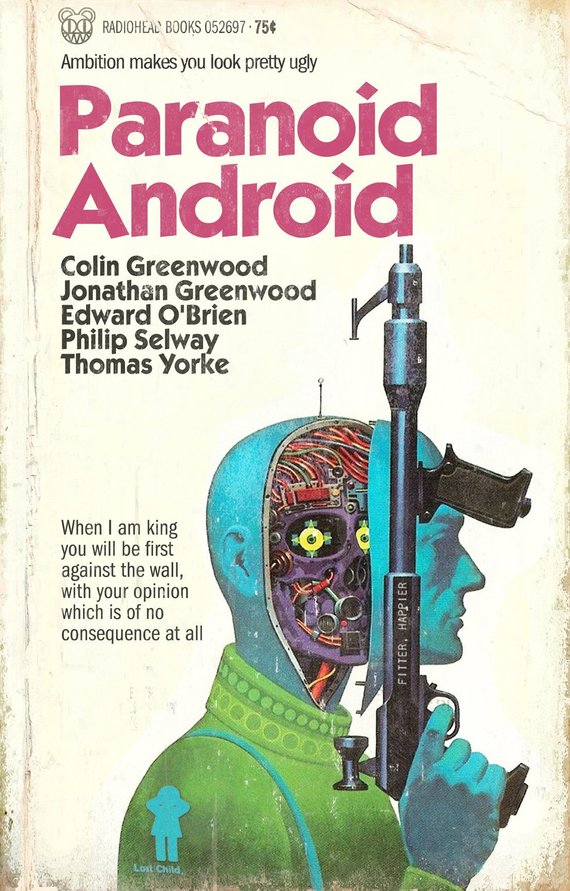

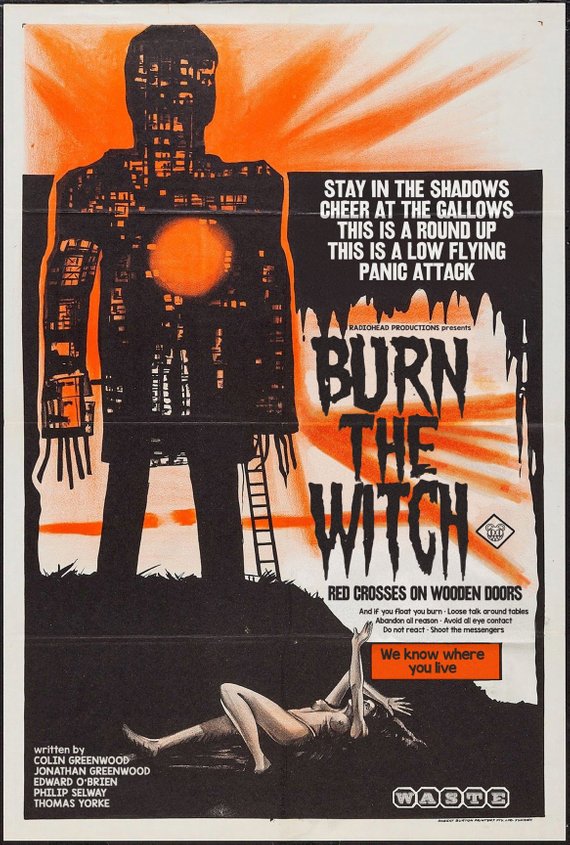

The Radiohead series does not fully abandon the pulp look—“Karma Police,” for example, gets the detective magazine treatment. But it does lean more heavily on later-20th century productions, like the 70s sci-fi cover of “Paranoid Android,” clearly inspired by Michael Crichton’s Westworld. Moon-Shaped Pool’s “Burn the Witch,” on the other hand, looks like a classic 50s Hammer Horror poster, but with a nod to Robin Hardy’s 1973 Wicker Man. (Both Crichton and Hardy have likewise been re-imagined for audiences who may never have seen the originals.)

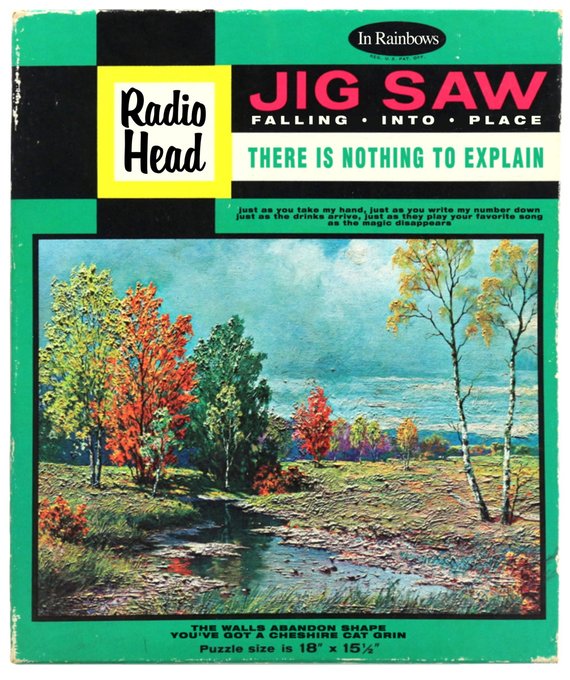

Perhaps the least interesting of Alcott’s riffs on the Radiohead catalog, “Jigsaw Falling into Place,” goes right for the obvious, though its idyllic, Bob Ross-like scene strikes a dissonant chord in illustrating a song that references closed circuit cameras and sawn-off shotguns. Speaking of obvious, maybe it seemed too on the nose to turn “Creep” into creepy pulp erotica. Still, I wonder how Alcott resisted. View and purchase in handmade print form all of Alcott’s songs-as-book covers, etc. at Etsy.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness