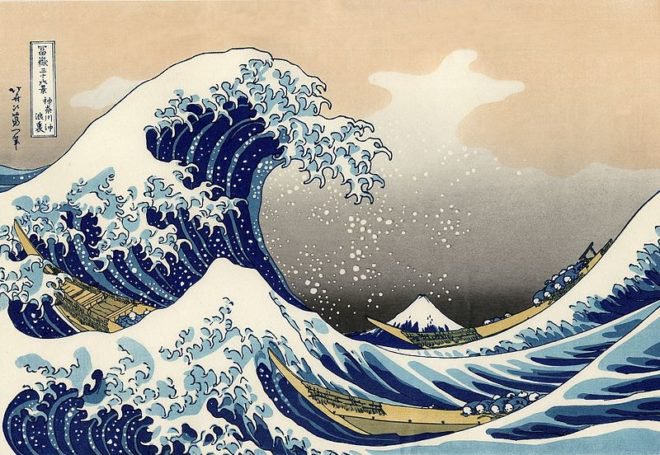

Since the moviegoing public first started hearing it twenty years ago, Wes Anderson’s name has been a byword for cinematic meticulousness. The association has only grown stronger with each film he’s made, as the live-action ones have featured increasingly complex ships, trains, and grand hotels — to say nothing of the costumes worn and accoutrements possessed by the characters who inhabit them — and the stop-motion animated ones have demanded a superhuman attention to detail by their very nature. It made perfect sense when it was revealed that Isle of Dogs, Anderson’s second animated picture, would take place in Japan: not only because of Japanese film, which opens up a vast field of new cinematic references to make, but also because of traditional Japanese culture, whose meticulousness matches, indeed exceeds, Anderson’s own.

Most of us first experience that traditional Japanese meticulousness through food. And so most of us will recognize the form of the bento, or meal in a box, prepared step-by-step before our eyes in Isle of Dogs, though we may never before have witnessed the actual process of carving up the wriggling, scurrying sea creatures that fill it.

One viewing of this 45-second shot is enough to suggest how much work must have gone into it, but this time-lapse of its 32-day-long shoot (within a longer seven-month process to make the entire sequence) reveals the extent of the labor involved. In it you can see animators Andy Biddle (who’d previously worked on Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, and before that his animated The Fantastic Mr. Fox) and Tony Farquhar-Smith painstakingly positioning and repositioning each and every one of the bento’s ingredients — all of which had to be specially made to look right even when chopped up and sliced open — as well as the disembodied hands of the sushi master preparing them.

Shooting stop-motion animation takes a huge amount of time, and so does making sushi, as anyone who has tried to do either at home knows. Performing the former to Andersonian standards and the latter to Japanese standards hardly makes the tasks any easier. But just as a well crafted bento provides an enjoyable and unified aesthetic experience, one that wouldn’t dare to remind the consumer of how much time and effort went into it, a movie like Isle of Dogs provides thrills and laughs to its viewers who only later consider what it must have taken to bring such an elaborate vision to life on screen. If you want to hear more about the demands it made on its animators, have a look at the Variety video above, in which Andy Gent, head of Isle of Dogs’ puppet department, explains the process and its consequences. “It took three animators, because it broke quite a few people to get it through the shot,” he says. “Seven months later, we end up with one minute of animation.” But that minute would do even the most exacting sushi master proud.

Related Content:

The Geometric Beauty of Akira Kurosawa and Wes Anderson’s Films

The History of Stop-Motion Films: 39 Films, Spanning 116 Years, Revisited in a 3‑Minute Video

How to Make Sushi: Free Video Lessons from a Master Sushi Chef

The Right and Wrong Way to Eat Sushi: A Primer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.