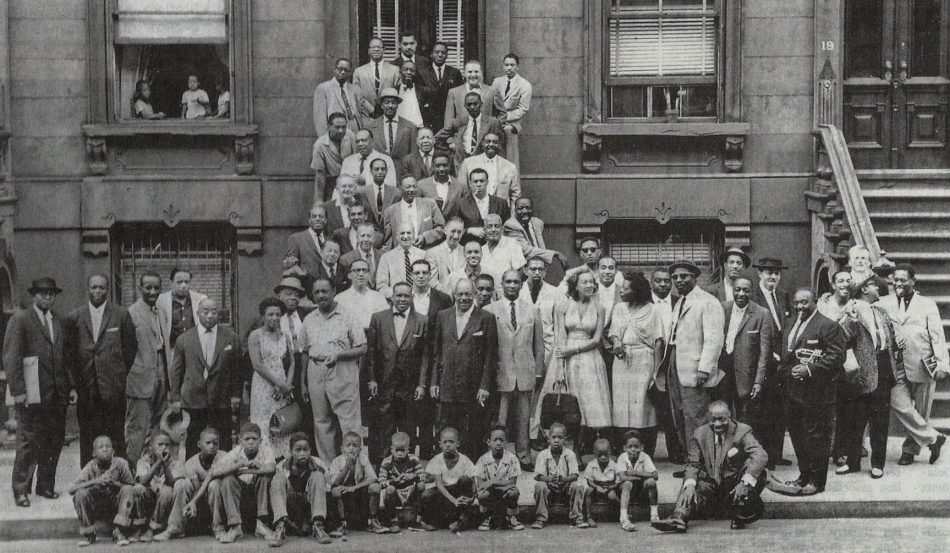

Image by Art Kane, via Wikimedia Commons

Sixty years ago, Art Kane assembled one of the largest groups of jazz greats in history. No, it wasn’t an all-star big band, but a meeting of veteran legends and young upstarts for the iconic photograph known as “A Great Day in Harlem.” Fifty-seven musicians gathered outside a brownstone at 17 East 126th St.—accompanied by twelve neighborhood kids—from “big rollers,” notes Jazzwise magazine, like “Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Count Basie, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Pee Wee Russell to then up-and-coming names, Benny Golson, Marion MacPartland, Mary Lou Williams and Art Farmer.”

Sonny Rollins was there, one of only two musicians in the photo still alive. The other, Benny Golson, who turns 90 next year, remembers getting a call from Village Voice critic Nat Hentoff, telling him to get over there. Golson lived in the same building as Quincy Jones, “but somehow he wasn’t called or he didn’t make it.”

Other people who might have been in the photograph but weren’t, Golson says, because they were working (and the 10 a.m. call time was a stretch for a working musician): “John Coltrane, Miles, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman.” And Buddy Rich, whom Golson calls the “greatest drummer I ever heard in my life” (adding, “but his personality was horrible.”)

The next year, everything changed—or so the story goes—when revolutionary albums hit the scene from the likes of Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Ornette Coleman, and Charles Mingus. These records pushed experimental forms, leaving behind the confines of both swing and bebop. But Kane’s jazz class photo shows us, Matthew Kessel writes at Vulture, “a portrait of harmony, old and new guard alike peaceably intermingling. The photo suggests that jazz is as much about continuity and tradition as it is about radical change.” The photo has since become a tradition itself, hanging on the walls of thousands of homes, bookshops, record stores, barbershops, and restaurants. (Get your copy here.)

Originally titled “Harlem 1958,” Kane’s image has inspired some notable homages in black culture. In 1998, XXL magazine tapped Gordon Parks to shoot “A Great Day in Hip Hop” for a now-historic cover. And this past summer, Netflix gathered 47 black creatives behind more than 20 original Netflix shows for the redux “A Great Day in Hollywood.” The photo also inspired a documentary of the same title in 1994 (at whose website you can click on each musician for a short bio). At the Daily News, Sarah Goodyear tells the story of how Kane conceived and executed the ambitious project for a special jazz edition of Esquire.

It was his “first professional shooting assignment and, with it, he ended up making history by almost by accident.” Goodyear quotes Kane’s son Jonathan, himself a New York musician, who remarks, “certain things end up being bigger than the original intention. The photograph has become part of our cultural fabric.” For longtime residents of Harlem, the so-called Capital of Black America, and a spiritual home of jazz, it’s just like an old family portrait. See a fully annotated version of “A Great Day in Harlem” at Harlem.org, and at the Daily News, an interactive version with links to YouTube recordings and performances from every one of the 57 musicians in the picture.

This month, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the photo, Wall of Sound Gallery will publish the book Art Kane: Harlem 1958, a retrospective with outtakes from the photo session and text from Quincy Jones, Benny Golson, Jonathan Kane, and Art himself. “The importance of this photo transcends time and location,” writes Jones in his forward, “leaving it to become not only a symbolic piece of art, but a piece of history. During a time in which segregation was very much still a part of our everyday lives, and in a world that often pointed out our differences instead of celebrating our similarities, there was something so special and pure about gathering 57 individuals together, in the name of jazz.”

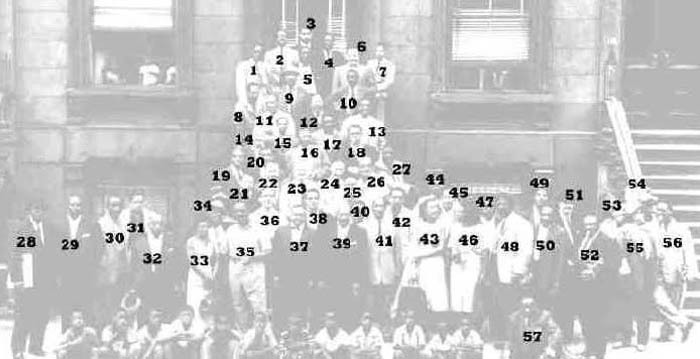

- Hilton Jefferson (1903–1968)

- Benny Golson (1929-)

- Art Farmer (1928–2003)

- Wilbur Ware (1923–1979)

- Art Blakey (1919–1990)

- Chubby Jackson (1918–2003)

- Johnny Griffin (1928–2008)

- Dickie Wells (1909–1985)

- Buck Clayton (1911–1993)

- Taft Jordan (1915–1981)

- Zutty Singleton (1898–1975)

- Henry “Red” Allen (1908–1967)

- Tyree Glenn (1912–1972)

- Miff Mole (1898–1961)

- Sonny Greer (1903–1982)

- J.C. Higginbotham (1906–1973)

- Jimmy Jones (1918–1982)

- Charles Mingus (1922–1979)

- Jo Jones (1911–1985)

- Gene Krupa (1909–1973)

- Max Kaminsky (1908–1994)

- George Wettling (1907–1968)

- Bud Freeman (1906–1988)

- Pee Wee Russell (1906–1969)

- Ernie Wilkins (1922–1999)

- Buster Bailey (1902–1967)

- Osie Johnson (1923–1968)

- Gigi Gryce (1927–1983)

- Hank Jones (1918–2010)

- Eddie Locke (1930–2009)

- Horace Silver (1928–2014)

- Luckey Roberts (1887–1968)

- Maxine Sullivan (1911–1987)

- Jimmy Rushing (1902–1972)

- Joes Thomas (1909–1984)

- Scoville Browne (1915–1994)

- Stuff Smith (1909–1967)

- Bill Crump (1919–1980s)

- Coleman Hawkins (1904–1969)

- Rudy Powell (1907–1976)

- Oscar Pettiford (1922–1960)

- Sahib Shihab (1925–1993)

- Marian McPartland (1920–2013)

- Sonny Rollins (1929-)

- Lawrence Brown (1905–1988)

- Mary Lou Williams (1910–1981)

- Emmett Berry (1915–1993)

- Thelonious Monk (1917–1982)

- Vic Dickenson (1906–1984)

- Milt Hinton (1910–2000)

- Lester “Pres” Young (1909–1959)

- Rex Stewart (1907–1972)

- J.C. Heard (1917–1988)

- Gerry Mulligan (1927–1995)

- Roy Eldridge (1911–1989)

- Dizzy Gillespie (1917–1993)

- William “Count” Basie (1904–1984)

Related Content:

1959: The Year That Changed Jazz

Hear 2,000 Recordings of the Most Essential Jazz Songs: A Huge Playlist for Your Jazz Education

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.