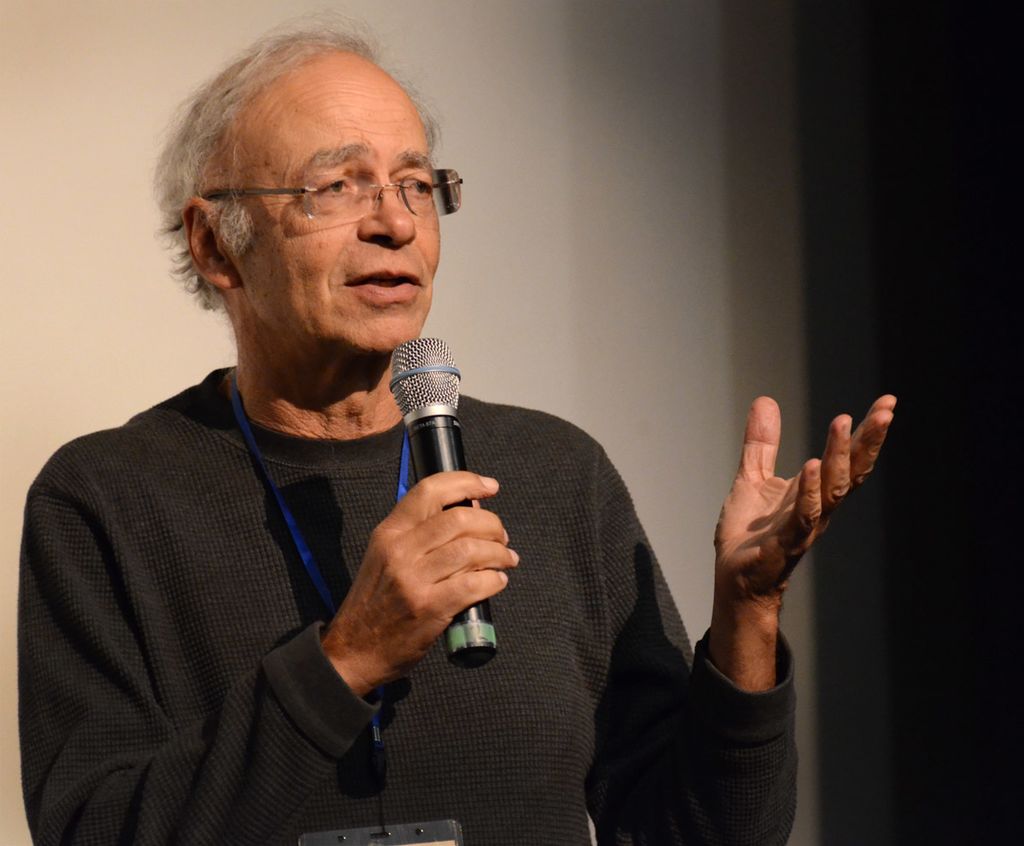

Photo of Peter Singer by Mat Vickers, via Wikimedia Commons

Australian bioethicist Peter Singer has made headlines as few philosophers do with claims about the moral status of animals and the “Singer solution to world poverty,” and with far more controversial positions on abortion and disability. Many of his claims have placed him outside the pale for students at Princeton, his current employer, where he has faced protests and calls for his termination. “I favor the ability to put new ideas out there for discussion,” he has said in response to what he views as a hostile academic climate, “and I see an atmosphere in which some people may be intimated from doing that.”

For those who, like him, make controversial arguments such as those for euthanizing “defective infants,” for example, as he wrote about in his 1979 Practical Ethics, Singer has decided to launch a new venue, The Journal of Controversial Ideas. As The Chronicle of Higher Education reports, the journal aims to be “an annual, peer-reviewed, open-access publication that will print worthy papers, and stand behind them, regardless of the backlash.” The idea, says Singer, “is to establish a journal where it’s clear from the name and object that controversial ideas are welcome.”

Is it true that “controversial ideas” have been denied a hearing elsewhere in academia? The widely-covered tactics of “no-platforming” practiced by some campus activists have created the impression that censorship or illiberalism in colleges and universities has become an epidemic problem. No so, argues Princeton’s Eddie Glaude, Jr., who points out that figures who have been disinvited to speak at certain institutions have been welcomed on dozens of other campuses “without it becoming a national spectacle.” Sensationalized campus protests are “not the norm,” as many would have us believe, he writes.

But the question Singer and his co-founders pose isn’t whether controversial ideas get aired in debates or lecture forums, but whether scholars have been censored, or have censored themselves, in the specialized forums of their fields, the academic journals. Singer’s co-founder/editor Jeff McMahan, professor of moral philosophy at Oxford, believes so, as he told the BBC in a Radio 4 documentary called “University Unchallenged.” The new journal, said McMahan, “would enable people whose ideas might get them in trouble either with the left or with the right or with their own university administration, to publish under a pseudonym.”

Those who feel certain positions might put their career in jeopardy will have cover, but McMahan declares that “the screening procedure” for publication “will be as rigorous as those for other academic journals. The level of quality will be maintained.” Some skepticism may be warranted given the journal’s intent to publish work from every discipline. The editors of specialist journals bring networks of reviewers and specialized knowledge themselves to the usual vetting process. In this case, the core founding team are all philosophers: Singer, McMahan, and Francesca Minerva, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Ghent.

One might reasonably ask how that process can be “as rigorous” on this wholesale scale. Though the BBC reports that there will be an “intellectually diverse international editorial board,” board members are rarely very involved in the editorial operations of an academic journal. Justin Weinberg at Daily Nous has some other questions, including whether the degree, or existence, of academic censorship even warrants the journal’s creation. “No evidence was cited,” he writes “to support the claim that ‘a culture of fear and self-censorship’ is preventing articles that would pass a review process” from seeing publication.

Furthermore, Weinberg says, the journal’s putative founders have given no argument “to allay what seems to be a reasonable concern that the creation of such a journal will foster more of a ‘culture of fear and self-censorship’ compared to other options, or that it plays into and reinforces expertise-undermining misconceptions about academia bandied about in popular media that may have negative effects…. Given that the founding team is comprised of people noted for views that emphasize empirical facts and consequences, one might reasonably hope for a public discussion of such evidence and arguments.”

Should scholars publish pseudonymously in peer-reviewed journals? Shouldn’t they be willing to defend their ideas on the merits without hiding their identity? Is such subterfuge really necessary? “Right now,” McMahan asserts, “in current conditions something like this is needed…. I think all of us will be very happy if, and when, the need for such a journal disappears, and the sooner the better.” Given that the journal’s co-founders paint such a broadly dire picture of the state of academia, it’s reasonable to ask for more than anecdotal evidence of their claims. A few high-profile incidents do not prove a widespread culture of repression.

It is also “fair to wonder,” writes Annabelle Timsit at Quartz, “whether the board of a journal dedicated to free speech might have a bias toward publishing particularly controversial ideas in the interest of freedom of thought” over the interests of good scholarship and sound ethical practice.

Related Content:

The 20 Most Influential Academic Books of All Time: No Spoilers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness